What do you think?

Rate this book

13 pages, Audible Audio

First published July 19, 2019

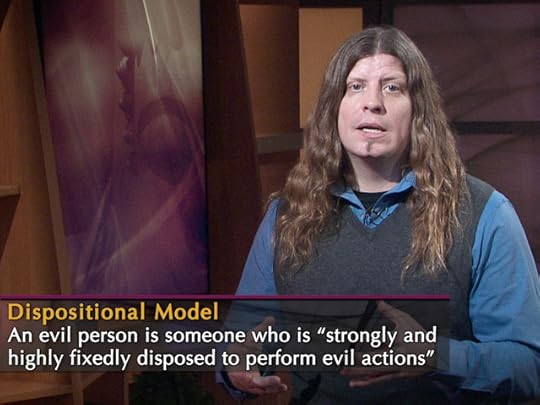

Calling someone evil is serious business, it marks out that someone is outside the moral community, by making someone evil we make the most serious moral accusation we have against them, but that accusation might end up justifying not only certain feelings we have against them but also certain responses

The philosopher Thomas Nagel considers the fact that our lives are mere blips on the cosmic screen, lasting only briefly. Nagel suggests that the factor that makes our lives absurd is “the collision between the seriousness with which we take our lives and the perpetual possibility of regarding everything about which we are serious as arbitrary, or open to doubt.” w We take ourselves seriously in the sense that we self-consciously pursue our lives. But when we step back from our lives and reflect on them and the reasons that drive us, things start to seem ungrounded, unjustified, and arbitrary. w To deal with or perhaps to avoid life’s absurdity, we try to find meaning in things that are bigger than we are. The problem with this, however, is that to eliminate absurdity, these bigger things must themselves be meaningful, their meaning must be clear to us, and the meaning they have must be meaningful to us. And so, when we step back from these bigger things and question them, the whole process starts over. w And this doubt cannot be laid to rest partly because once we step back from our lives, we consider them from a perspective “in which no standards can be discovered.” The step backward is not a step into the realm of the truly meaningful; it is a step into meaninglessness. w We only really need to do something if we think that life’s absurdity is a problem in need of a solution, and Nagel, unlike Camus, suggests that it’s not. Rather than being a problem, the absurdity of the human condition is one of its defining features.

The psychologist Daniel Wegner offers one way to test part of Freud’s theory. Wegner observes that when we want to stop thinking about something, we have a hard time suppressing the thought. w To explain this, Wegner noted that there are two cognitive processes working against each other: one process that tries to suppress the thought and another that monitors for the suppressed thought. The monitoring process ends up triggering the very thoughts we’re trying to suppress. w With this in mind, Wegner hypothesized that something similar might be happening while we’re sleeping. When we sleep, many of mechanisms that help us suppress thoughts, such as attention, control, and working memory, become deactivated, especially during rapid eye movement (or REM) sleep

The philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre resists the idea that we have tailor-made natures that determine who we are. He argues that in every moment of our lives we are making ourselves through our choices. w Picking up on this, Robert Kane, one of the most influential contemporary philosophers of free will, argues that each of our genuinely free actions is “the initiation of a ‘value experiment’ whose justification lies in the future and is not fully explained by the past.” Kane posits that in making a choice, people say, “‘Let’s try this. It is not required by my past, but is consistent with my past and is one branching pathway my life could now meaningfully take.’”

An ignorant mind is precisely not a spotless, empty vessel, but one that’s filled with the clutter of irrelevant or misleading life experiences, theories, facts, intuitions, strategies, algorithms, heuristics, metaphors, and hunches that regrettably have the look and feel of useful and accurate knowledge.