Note: This review contains ‘spoilers,’ especially if the reader is not already familiar with the subjects of this historical biography and what happened to them.

* * * *

I found the real-life character of Effie Gray as narrated in these pages to be a somewhat disagreeable and not entirely sympathetic figure, but her story interwoven with Ruskin’s and Millais’ is a fascinating one, expertly stitched together here from exclusive access to the necessary primary documents, chiefly comprised of correspondence. While Effie Gray, eventually Mrs. Millais, seems to display certain very human vices, such as degrees of vanity, maternal callousness, and class pride (along with less than progressive views on certain subjects and activists of her time), their basis in life’s hardships and the social order are well documented and explored in the biography.

The book provides rare insight into both men of genius in Effie’s orbit, the influential scholar John Ruskin and mesmerizingly talented Pre-Raphaelite painter John Everett Millais.

Somehow, Ruskin, Gray’s estranged/disgraced first husband, nevertheless emerges even more shrouded in mystery in his ill-fated journey through these pages, as their story is told incrementally through his wife’s lens. Her early letters exercise considerable discretion, masking the extent and nature of her unhappiness, such that her eventual candor and assertions of lifelong, unhealable psychic scars from their failed union bear witness to a potent blend of secret shame and bolder hindsight. Since Effie’s words hold sway as the primary voice guiding the biography, the overall account establishes John Ruskin as an emotional and psychological abuser, beholden to controlling parents in an oppressive familial closeness that seemingly conspired to smother Effie’s own ambitions, starve her of affection, and extinguish her hopes of marital/personal fulfillment. Meanwhile, Ruskin’s own vehement self-defense (namely, of his virility) stayed sealed for nearly 100 years and was never entered into evidence in the court case that infamously dissolved their marriage, at which time he apparently took the high road; at great personal cost to his reputation and dignity, eager to dispense with the matter, he refused to contest her case, and indeed testified that her “conduct” was beyond “reproach” (p. 126).

Resisting the urge to simplify their complex story, I appreciate how the biographer Suzanne Fagence Cooper takes care not to further impugn Mr. Ruskin’s character, more than history and court verdict have already done. Instead, she even-handedly presents the known details of their passionless, bizarre, unfortunate, and fraught life together and its aftermath, while also conscientiously acknowledging and respectfully honoring Ruskin’s profound contributions, intellectual sensitivity, and gifts of insight as both visionary artistic advocate and critical giant of aesthetic history. Clearly, it was into his rich intellectual (and spiritual) life, not his marriage, that Ruskin poured his passion and soul.

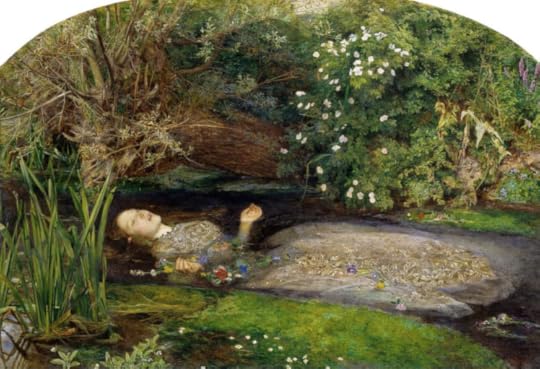

As for John Everett Millais, his art takes center stage throughout much of the narrative and serves as another level of storytelling and family biography in its own right. His groundbreaking early and lucrative later styles are explored, both aesthetically and as shaped by other factors (financial and professional demands). As Beatrix Potter wrote in her journals, his use of focus in signature paintings such as Ophelia (1851/2) is especially striking: “Focus is the real essence of pre-Raphaelite art, as is practiced by Millais. Everything in focus at once, which though natural…produces on the whole a different impression from that which we receive from nature” (quoted in Linda Lear’s Potter biography, p. 63). Fagence Cooper further explains that this movement drew inspiration from medieval paintings in which “[e]ach model, from the smallest leaf upwards, was treated as an individual” (p. 85). She frequently pauses to analyze, thoughtfully, many of Millais’ paintings and drawings with skill and nuance, tracing the evolution -- or in his critics’ eyes, gradual loosening (brushstrokes) and popularizing (subject choices) -- of his work. I only wish more of these were included in the book’s illustrations pages; be sure to read with Internet image access at the ready. You will not find much at all in these pages about Effie’s level of acquaintance with the other Pre-Raphaelites or the women in their lives, such as model/artist Lizzie Siddal (d. 1862). There is passing reference to William Holman Hunt’s rocky relationship with Annie Miller as noteworthy cautionary context in young Millais’ inner circle that informed his own disinclination toward romantic love pre-Effie, i.e. prior to his all-consuming infatuation with the picturesque Mrs. Ruskin (p. 106). Fagence Cooper’s pages devoted to synopsizing the fateful, provocative Pre-Raphaelite/Ruskin alliance left me eager to reread exquisite passages of Ruskin’s own masterwork The Stones of Venice (which intrigued me decades ago when perusing theories of the vibrant grotesque elements in medieval art).

The final chapters probe into the Millais’ marital home in later decades with close scrutiny of their familial and social lives, although shining very little light on their relationship itself beyond the practical arrangement of duties. It is not especially clear the extent to which Effie’s feelings toward John Everett Millais were passionate, either at the outset or in later years, but there is a sense of loyalty and constancy of shared purpose. Children and close extended family encircled this power couple of the art world, and the biography deftly highlights the intricate role that art played as the defining purpose of their palatial residence and the stage on which the Millais children grew up in the public eye. Even in Effie’s successful second marriage, the domestic lives of the Millais and Gray clan remained steeped in past and new layers of personal tragedy, the cumulative effect of which seems to have been endowing Mrs. Millais with a remarkable kind of stoicism.