Graham Greene once called "Travels With My Aunt" as the only book that he wrote "for the fun of it'", thus indulging his manic tendencies to the hilt (as opposed to what he called his "depressive tendencies") with his tongue lodged firmly in his cheek. Many were however unaware of the truth that in the world of Greene's literature, even fun and frolic are tinged with sadness and melancholia to create even in a novel as swinging as this a dual portrait of the human condition - comic and tragic, hilarious and heartrending, cheerful and nostalgic.

All these paradoxical shades lend "Travels With My Aunt" its unique identity in his oeuvre. It is not as freewheeling just as "The Comedians", one of his darkest works, too is relieved by pitch-black humour of Jones' clumsy Quixotism and the naive vegetarian idealism of the Smiths. One should remember that Greene gave up dividing his novels as "entertainments" and "serious novels" with "Our Man In Havana" and the result was an even more eclectic body of work that could be philosophical, political or even deeply personal. His concerns ranged across a very wide spectrum - in one novel, he chronicled the doomed machismo of the Paraguayan rebels pitted against tyrannies funded by USA; in another, he could chart the depths of greed and self-loathing to which people, either broken or mediocre, could sink abominably.

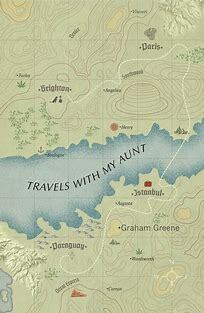

But "Travels With My Aunt" has, for so long, enjoyed a reputation (not at all undeserving) of being Greene's funniest novel (the phrase rolls off the tongue of many a critic easily like a lazy opinion) that one might almost miss just how melancholic and poignant it is. Greene's two key themes were "ageing" and "death" and it should not be forgotten that the author himself was in his sixties, uncertain of his own health and well-being. And so, Aunt Augusta Pulling, for all her inexhaustible spirit of mischief, is revealed in a second reading to be an elderly woman seeking permanence after a lifetime of casual romance, colourful characters (some of whom could not resist her charms too) and some utterly anarchic incidents and memories. This lively lady is willing to call it a day. There are indeed memorable and mesmerising travels in store for her - Greene takes her back to Brighton and forward into Istanbul, then back again to Boulogne and finally forward to her journey's end in orange-scented Paraguay where she finally hopes to reunite with the man she still loves.

The fact that this man (to whom I will turn in sometime) is crooked and unscrupulous (which is why the Interpol seems to be interested in her too) has little to do with how charming he seems to her even at this age. This is further evidence of quite why Aunt Augusta Pulling, in her serious lack of prejudice, is one of Greene's prime creations as a character. There is something so infinitely alluring and intriguing about her, as she flits across the novel; she is much more than the archetype prankster upsetting the civility of manners in the fashion of someone out of a Hector Hugh Munro story or a Wodehouse novel even as she orchestrates premature cremations and also smuggles gold quite comfortably across European borders. Her tall tales eventually sound utterly believable and yet, while they reveal everything about her past, they also keep the fascinating mystery of her personality guarded. Till the end, she remains wonderfully enigmatic - the secret of her soul remains elusive.

There are many secrets, then, that Greene stashes away devilishly in this novel that we are completely unprepared for. There is the same flair for suspense and intrigue flowing through the novel too; there is smuggling and pot-smoking, there is even espionage on the menu and Greene masterfully weaves these elements into the story without ever losing his grasp of his "human factor" - the very resonant emotions of love and longing, camaraderie and solitude, paranoia and suspense, humour and sorrow and the blitheness of youth and ageing wisdom. The latter half of the novel swings into the territory of a geopolitical thriller where nobody or nothing is what he, she or it seems but even Augusta's memories have an element of comedic suspense to them; we keep reading them feverishly, enchanted, amused and thrilled, just like her nephew, wondering where would they lead or end. And the author keeps the startling truth of Augusta's real identity a fabled secret till the very last page, only dropping hints and allusions.

As a foil to Augusta's search for permanence, we have her fifty-something nephew Henry Pulling who slowly and steadily craves to escape this state of humdrum permanence he has already found as a retired bank manager. If Aunt Augusta is a mystery, Henry Pulling is even more mysterious than his aunt. He is a fascinating, enjoyably naive narrator but even his simplicity is spurious. For all his mild-mannered demeanour, he is capable of the same impulsive mischief as his aunt and even the covert capacity for romance that his long deceased father was known for. If Augusta is the lingering puzzle of the novel, Henry is its heart and soul. We see the world of his aunt's eccentric and illicit memories and experiences through his eyes; we are amused by Curran's dog churches and doggish fidelity, were bemused by Uncle Jo's lust for life and travel and we are also scandalised and then thrilled by other experiences because we see and drink them all through Henry himself, struck with boyish wonder and outrage but also willing to believe and surrender to its charms.

Henry, Augusta, Uncle Jo, Curran...the entire novel is rounded off, in typical Greene fashion, with a truly memorable cast of characters; perhaps no other author since the days of Dickens could write such fascinatingly believable characters as Greene could do it. One feels as if they will all be transfixed in memory long after one has read the last page and closed the book shut feeling exhilarated and moved. Perhaps, in the languid lawlessness of Paraguay, Mr. Visconti is still running his import-export business and spouting Machiavellian wisdom with many a glass of champagne; old Hatty might still be there in her tea room in Brighton, delivering prophecies over leaves of Lapsang Souchong; Tooley surely must have missed the pill and her father, the mundane CIA agent O'Toole, must still be keeping notes of all the times when he has passed urine. And as for poor Wordsworth, his body is still lying in the shade of the wood, doomed by his clumsy innocence and inexplicable love for his "bebi gel" - who is blissfully ignorant of his real feelings. Or he might be speaking out loudly through the mike from the flat above the Crown and Anchor even today.

"Travels With My Aunt" is also one of Greene's most affectionately English novels and it feels as if the author also intended to pay a fitting ode to the land from where he was departing (but to which, unlike Henry, he would return whenever possible). The humdrum suburbia of Southwood that is Henry's abode for so long is rendered evocatively; there are almost lovely and poignant allusions to Browning and Tennyson and Walter Scott and even the humour has that rich acid wit, not to forget that admirable English hobby of carrying books along on a journey. Speaking of journeys, this book does indeed capture all the excitement and apprehension of a real journey, be it in the Orient Express bound on its way across the continent or the small boat steaming in the rivers between two South American countries. And Greene also crams in the most delicious cultural allusions from the Ashes to the Beatles, from Andy Warhol to Leonardo Da Vinci and yet every detail matters, everything is significant to the story too.

And yet, despite all the frolic and fun, "Travels With My Aunt" will be most memorable as a tender, timeless tale of love and living life to the fullest. Who else could it have been than the twentieth century's greatest, most dexterous storyteller himself to deliver it?