What do you think?

Rate this book

96 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1982

"I had not slept an hour a night for a fortnight together, and for five days together not a wink." (1)

"Being a man with a secret was a full-time role...

"In this spawning of multiple selves I seemed to see the awesome force of my love, which in turn served to convince me anew of its authenticity.

"Perhaps this sense of displacement will account for the oddest phenomenon of all, and the hardest to express. It was the notion of a time out of time, of this summer as a self-contained unit separate from the time of the ordinary world.

"The events I read of in the newspapers were, not unreal, but only real out there, and irredeemably ordinary; Ferns, on the other hand, its daily minutiae, was strange beyond expressing, unreal and yet hypnotically vivid in its unreality...

"There was no sense of life messily making itself from moment to moment. It had all been lived already, and we were merely tracing the set patterns, as if not living really, but remembering...

"Now I saw this summer as already a part of the past, immutable, crystalline and perfect. The future had ceased to exist. I drifted, lolling like a Dead Sea swimmer, lapped round by a warm blue soup of timelessness."

"My dear Doctor, expect no more philosophy from my pen. The language in which I might be able not only to write but to think is neither Latin nor English, but a language none of whose words is known to me; a language in which commonplace things speak to me; and wherein I may one day dare have to justify myself before an unknown judge.In the letter Newton also accuses Locke of endeavoring "to embroil [him] with woemen."

"Love. That word. I seem to hear quotation marks around it, as if it were a title of something, a stilted sonnet, say, by a silver poet. Is it possible to love someone of whom one has so little?(I quote another breathtaking passage after the rating.) Sex scenes are notoriously difficult to write: even greatest authors sometimes stumble and produce passages that sound ridiculous, technical, disgusting, or just plain vulgar. Mr. Banville offers a beautifully written, delicate, almost metaphorical scene of physical love between the narrator and Ottilie. I am not able to quote because the entire longish paragraph would be needed to fully convey the beauty.

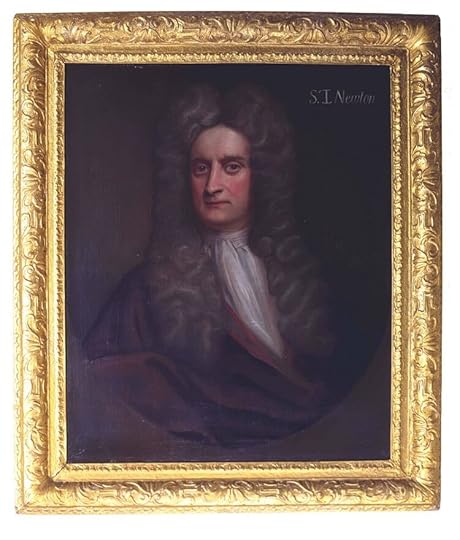

“Sitting at my table before the window and the sunlit lilacs I thought of Canon Koppernigk at Frauenburg, of Nietzsche in the Engadine, of Newton himself, all those high cold heroes who renounced the world and human happiness to pursue the big game of the intellect. A pretty picture - but hardly a true one."

Edward farfulló unas palabras y salió del cuarto. Bunny observó cómo la puerta se cerraba tras él y entonces se volvió con ansiedad hacia Charlotte.

-¿Cómo está?

Ojos encendidos, muriéndose de ganas de saber, dime, dime....

Hubo un momento de silencio.

-Oh- dijo Charlotte-, no... quiero decir... no está mal, ya sabes.

Bunny puso la taza en la mesa y se sentó, su rostro podía muy bien ser un estudio de dolor y compasión, su cabeza se movía de un lado a toro.

-Pobrecita de ti, pobrecita... -Entonces me miró a mí-. Supongo que usted sabe de qué se trata... ¿no?

-No- dijo Charlotte instantáneamente.

Bunny se tapó la boca con la mano.

-Ay! Lo siento.

Edward volvió con la botella de whisky