Ah, thank God, I finished reading the book! It is sort of unputdownable but, at the same time, deserves to be dashed against the wall! The only reasons I didn’t toss it is because of my own respect for books and my sympathies towards David. Let me explain.

The glaring problem which we encounter as soon as we open the book is that there is no Table of Contents or even Chapters! There is not even the index at the back of the book! Sure, there are seven “chapters” but they and their sections (which Wallace refers to as §) flow continuously like one single thread from page one to last page, with lots of footnotes and embedded glossaries and interpolations. It is all a new and unique style of writing—appreciable—but the nub is that it is very difficult to find stuff because—remember—there is no index or even chapter names! The book is filled with good information about the history, and even the math of infinity is presented very well, but when I needed to quickly go back and reread certain items, it was difficult as hell! Although, I must admit, however difficult it was, I could find what I wanted to reread by flipping back and searching and, in fact, I felt I gained something by working hard to find what I was looking for instead of they being given—in the index/Table of Content—on a platter. Maybe that was David’s real intention but, believe me, it was painfully frustrating! The other side-effect of this one continuous drool of a writing—despite quote-unquote chapter divisions—is that the various topics that are being delivered don’t seem to make a coherent whole; it becomes difficult to see the forest for the trees by connecting everything that’s being said. The solution—for me—was to take breathers in between, lift my head, cuss, and think about what was being said, and how it connects together, all within the context in which it is being said. In other words, the writing style coerced me to think hard, work hard, and thereby decipher the contents which, again, may have been David’s intention, but it could also be my own prior knowledge of infinity and its history. I sincerely believe that some knowledge of math is required to enjoy this book.

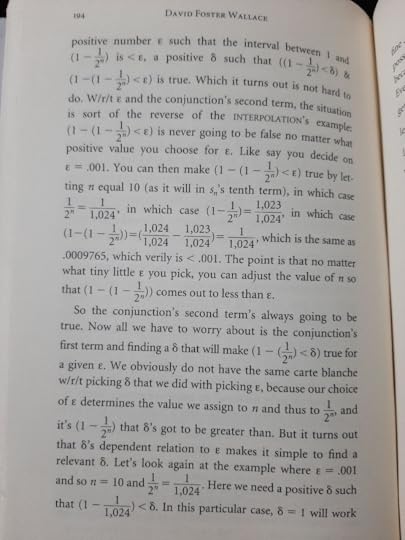

The book starts about 2400 years ago, with Zeno’s paradox, talks about Greek’s mistrust and difficulty to accept infinity even in the face of knowledge of irrational numbers staring at them, Aristotle’s misleading potential-infinity vs. actual-infinity (and how the Church grabbed his theories of infinity, and of course his geocentric world too, in order to support God centric universe), introduces number line of integers, how rational number line is not continuous and has holes, and how transcendental irrational numbers fill in these holes, converges quickly on to Dedekind’s schnitt—or cut—to demonstrate irrationals, Cantor’s Set Theory, diagonalization method, his Dimension Theory, levels of infinites, power sets, cardinality and ordinality, touches Gödel’s incompleteness theorems, opening up to outstanding paradoxes in the Axiomatic Set Theory’s dealings with infinities. In other words, we come full circle: over the centuries, one set of mathematical paradoxes gets resolved only to open up new ones and mathematical research keeps chugging along! The punch of real Set Theory of infinities, you’ll see, is mostly in the last third of the book—that is, if you prevail! Difficult, but doable!

In the first few pages, David mentions that many people who worked on infinity turned mad or became depressed and were confined to mental hospitals, or were “on the spectrum,” many died very young, and some committed suicide. Sadly, David himself suffered from depression and committed suicide. I have a sneaking suspicion that not only he knew it was coming but also this book was meant to drop hints, or maybe a call for help. His thinking—we can easily see in his writing style—is recursively looping around, and sometimes jumps around from one thing to another but, in the end, finds its way back to whatever he was trying to say in the first place, something like how a musician improvises by going off and off and eventually unwinds back to fit into the original piece, or how a recursive computer program unwinds from the LIFO stack. Yes, Hofstadter’s Gödel, Escher, Bach all over again! He has tried to fit in a lot of information in this book (with few mistakes which most laypeople will not notice) and the historical perspective and the math—more math than history, which was good for me—are presented, all in one place. However, personally, since I am more interested in the math of infinity, I have to jump ship to explore the many "Roads to Infinity," (by John Stillwell). I am glad, though, for completing the book and would probably use it as a quick reference for historical perspective.