What do you think?

Rate this book

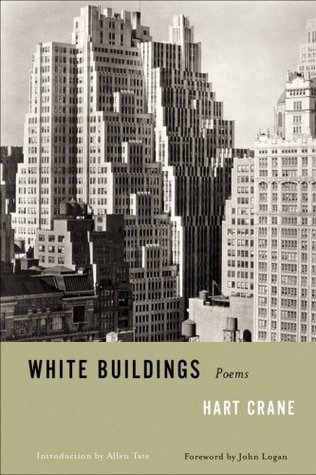

96 pages, Paperback

First published December 1, 1926

For The Marriage of Faustus and Helen

"And so we may arrive by Talmud skill

And profane Greek to raise the building up

Of Helen's house against the Ismaelite,

King of Thogarma, and his habergeons

Brimstony, blue and fiery; and the force

Of King A baddon, and the beast of Cittim;

Which Rabbi David Kimchi, Onkelos,

And A ben Ezra do interpret Rome. "

-THE ALCHEMIST.

I

The mind has shown itself at times

Too much the baked and labeled dough

Divided by accepted multitudes.

Across the stacked partitions of the day-

Across the memoranda, baseball scores,

The stenographic smiles and stock quotations

Smutty wings flash out equivocations.

(...)

Distinctly praise the years, whose volatileThe poems in general present themselves as high walls of language, impasto'd sound surfaces, with meanings not always clear. I have read the following lines from "Voyages," for instance, over and over and still have no idea of what it means:

Blamed bleeding hands extend and thresh the height

The imagination spans beyond despair,

Outpacing bargain, vocable and prayer.

In signature of the incarnate wordAs is typical of Crane, the syntax is hard to grasp (for one thing, what is the object of the verb "shoulders"?), the diction Latinate (signature, incarnate, transpiring, insinuations, inviolably, latitudes), and the topic only vaguely discernible (erotic love and the sea as holy instances of word made flesh?). All the pleasure is in the play of words, the language's decoration of the high topic, words hung like garlands around sex and death and ocean.

The harbor shoulders to resign in mingling

Mutual blood, transpiring as foreknown

And widening noon within your breast for gathering

All bright insinuations that my years have caught

For islands where must lead inviolably

Blue latitudes and levels of your eyes,—

In this expectant, still exclaim receive

The secret oar and petals of all love.

There is a displacement, in Crane's poetry, of the language of the body to the language of the landscape...Although such displacement (one kind of metaphor) is general in poetry, one might find a hint in the particular appearance of it in this "grandmother" poem that Hart Crane's overt homosexuality is in part a defense against admitting the physical feeling for the grandmother or surrogate mother.It takes a special kind of tastelessness to think that one of the volume's most translucent and moving poems, "My Grandmother's Love Letters," would be clarified by some overt oedipal gesture in conformity to mid-century Freudian dogma. The poem itself beautifully warns us against all coarseness in reading and interpretation:

Over the greatness of such spaceAllen Tate's original introduction to the volume, however, is useful and concise, explaining Crane's poetic and its historical context. Crane, Tate says, must write poetry in the modern world, which has lost the stability and coherence previously provided by Christianity and organic social forms. The modern poet, therefore, must "construct and assimilate his own subjects," whereas a pre-modern poet such as Dante only had to "assimilate his," since his society furnished him a subject of sufficient dignity and beauty for poetic treatment. Because Crane is not an Eliotic conservative but a Whitmanian affirmer of the American city, nostalgia or myth can provide him no recourse; the ship really has sailed, to invoke a nautical metaphor appropriate to Crane's imagery, and the poet thus has to extrude his material from his own inner imaginative vision. Tate explains that this is why Crane's poetry is so often obscure. Unlike Dante or even Eliot, whose apparently difficult poetry becomes clearer and clearer as you grasp the traditional meanings of their symbols, Crane's symbols may have no traditional (or transpersonal) meaning at all:

Steps must be gentle.

It is all hung by an invisible white hair.

It trembles as birch limbs webbing the air.

[Crane's] theme never appears in explicit statement. It is formulated through a series of complex metaphors which defy a paraphrasing of the sense into equivalent prose. The reader is plunged into a strangely unfamiliar milieu of sensation, and the principle of its organization is not immediately grasped. The logical meaning can never be derived (see Passage, Lachrymae Christi); but the poetical meaning is a direct intuition, realized prior to an explicit knowledge of the subject-matter of the poem. The poem does not convey; it presents; it is not topical, but expressive.That is very well said. And it implies that the best way to read Crane is to let him wash over you (more sea images), let his words and pictures saturate (again!) your own sensibility. Drop the margin-poised pencil, forget the dictionary of myth and symbol, and plunge in. Here, for instance, is a stanza from one of the poems Frank judges to be without logical meaning, "Lachrymae Christi":

(Let sphinxes from the ripeThis is both incoherent, even to the point of its being ungrammatical, and yet somehow emotionally intelligible: "vermin and rod / No longer bind," "tendoned loam"—I do feel it.

Borage of death have cleared my tongue

Once again; vermin and rod

No longer bind. Some sentient cloud

Of tears flocks through the tendoned loam:

Betrayed stones slowly speak.)

The interests of a black man in a cellarI think the judgment is "tardy" because, in Crane's view, the black man is only the latest or most explicit instance of the social exclusion to which the modern poet testifies. The problems with that self-serving notion hardly need elaboration—yet if one reverses the priority in the metonymy (from black man/poet to poet/black man) so that the text redefines racism as the abjection of the black man in the same terms in which the poet is also abjected (licentiousness, laziness, primitivism, etc.), then it makes a certain sense, and a more charitable reading is possible.

Mark tardy judgment on the world's closed door.

Gnats toss in the shadow of a bottle,

And a roach spans a crevice in the floor.

Compass, quadrant and sextant contriveThe first line and a half of this concluding stanza show how aphoristic Crane can be, demonstrate his love not only of Melville but of Dickinson. What better tribute to a writer who could navigate the sea but also what was beyond the farthest tide?

No farther tides ... High in the azure steeps

Monody shall not wake the mariner.

This fabulous shadow only the sea keeps.

As, when stunned in that antarctic blaze,I have read every poem in the volume at least twice and some many more times than that, but I need to go on re-reading "For the Marriage of Faustus and Helen" and "Voyages," not to mention "Wine Menagerie" and "Repose of Rivers."

Your head, unrocking to a pulse, already

Hallowed by air, posts a white paraphrase

Among bruised roses on the papered wall.

The apple on its bough is her desire,—This poem is a little guide (an "abstract") to Crane's poetry, counseling a refusal of the desire for knowledge that would make any poetry a matter of allegory. Don't desire to consume the poem, but rather become the poem, chant the poem, let the poem possess you. Crane boldly re-writes Genesis to find the source of the Fall in the desire for knowledge, and he redeems Eve by turning her into Daphne, rebuke to the arrogant Apollonian poet, just as he had conflated Christ with Dionysus in "Lachrymae Christi." But even to advance such an advocacy for non-meaning, Crane had to invoke tradition, which is to say meaning. And it is no wonder that a philistine like myself, lost in novel-world, would prefer such a poem with its foregrounded narrative and meta-narrative.

Shining suspension, mimic of the sun.

The bough has caught her breath up, and her voice,

Dumbly articulate in the slant and rise

Of branch on branch above her, blurs her eyes.

She is prisoner of the tree and its green fingers.

And so she comes to dream herself the tree,

The wind possessing her, weaving her young veins,

Holding her to the sky and its quick blue,

Drowning the fever of her hands in sunlight.

She has no memory, nor fear, nor hope

Beyond the grass and shadows at her feet.