What do you think?

Rate this book

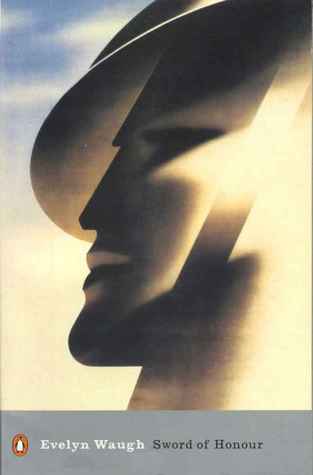

694 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1965

Waugh himself lived to lament the Second Vatican Council and to deplore the abolition of the Latin Mass - which meant that he became not more Catholic than the Pope but more curmudgeonly than his own confessors and more conservative than the Church itself. This has the accidentally beautiful result of making Sword of Honour into a literary memorial not just for a lost world but for a lost faith. In Catholic doctrine one is supposed to hate the sin and love the sinner. This can be a distinction without a difference if the "sin" is to be something (a Jew, a homosexual, even a divorcee) rather than to do something. Non-Christian charity requires, however, that one forgive Waugh precisely because it was his innate - as well as his adopted - vices that made him a king of comedy and of tragedy for almost three decades.Hitchens lays the ground for this conclusion by pointing out that Guy Crouchback, the protagonist of the trilogy, has to be taken as a stand-in for Waugh himself, since he's given the same day, month and year of birth as was the author's. And he expresses views about things that happened in the areas of Europe to which Waugh was posted during WW II that, when I read the book, I assumed to be ironic in the extreme, but perhaps actually reflected the author's own thinking. For example, Hitchens quotes from Waugh's private journal - "The Russians now propose a partition of East Prussia. It is a fact that now the Germans represent Europe against the world." - and continues, "The long and didactic closing stages of Sword of Honour are amazingly blatant in the utterance they give to this rather unutterable thought. Guy Crouchback regards the Yugoslav partisans as mere ciphers for Stalin, sympathizes with the local Fascists, and admires the discipline of the German occupiers. We know from many published memoirs that Waugh himself was eventually removed from this theater of operations for precisely that sort of insubordination."

... two years before when he read of the Russo-German alliance, when a decade of shame seemed to be ending in light and reason, when the Enemy was plain in view, huge and hateful, all disguise cast off; ... now that hallucination was dissolved [...] and he was back [...] in the old ambiguous world [...] and his country was led blundering into dishonour.