What do you think?

Rate this book

210 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1989

“No puedo permitirme disponer de todo mi tiempo y no tener en quién pensar, porque si lo hago, sino pienso en alguien sino sólo en las cosas, si no vivo mi estancia y mi vida en el conflicto con alguien o en su previsión o anticipación, acabaré no pensando en nada, desinteresado de cuanto me rodea y también de cuanto pueda provenir de mí.”

“nuestros hombres y en nuestras mujeres, en los que ya han sido nuestros o lo podrían ser, en los que ya conocemos y en los que nunca conoceremos, en los que fueron jóvenes y en los que lo serán, en los que han estado ya en nuestras camas y en los que nunca pasarán por ellas”

“miré abiertamente al rostro de Clare Bayes y, sin conocerla, la vi como alguien que pertenecía ya a mi pasado. Quiero decir como alguien que ya no era de mi presente, como alguien que nos interesó enormemente y dejó de interesarnos o que ya ha muerto, como alguien que fue o a quien un día ya antiguo condenamos a haber sido, tal vez porque ese alguien nos había condenado a nosotros a dejar de ser mucho antes.”

1. And I enjoyed the great consolation (or perhaps even the immense pleasure) of proposing the impossible and knowing that it would be rejected: for it is precisely the recognition that it is impossible and the certainty of rejection - a rejection that the person who proposes the impossible and takes the floor first in fact expects - that allows one to hold nothing back, to be vehement and more confident in expressing one's desires than if there were the slightest risk of their being satisfied.I have since bought four more books of JM's already. If ever you find yourself that way inclined, do seek out the handsome Penguin Modern Classics Editions. They just feel right somehow.

2. ... and I was surprised to find myself daring to say (much too early in the conversation) things I hadn't even foreseen myself saying or was even sure I wanted to say, either at the beginning or perhaps even at the end (the word "together", the word "son", the word "stepson"), but I thought, too, that my last sentences, including the very last, had been acceptable within the narrow range of possible varieties of behaviour in non-blood relationships. Now it was Clare's turn to be surprised, at least a little, although, inevitably, her surprise was only a pretence. But her pretence took the form of not being surprised, which is one way of handing back the surprise (or its pretence) to the other side.

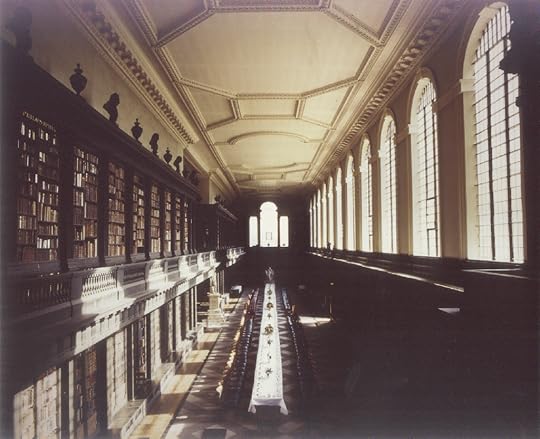

I saw the child Eric, Claire's son, only once and that was when the days of his unexpected stay in Oxford were coming to an end and my emotional instability was at its height (for if you have already been deprived of something for some time or – its real duration being of little importance – have experienced it as having gone on for a long time, as perhaps being endless, the fact that an end to it is now in sight pales into insignificance beside the continuing fact of your deprivation; I mean that the mere juxtaposition of these two things is not in itself enough for you to perceive as being at an end something which, though about to end, is still not over, and what prevails is the fear that by some ill luck – by some misfortune, the opposite of what you have foreseen – that long-accumulated, patient present might yet go on forever: you experience not relief but anxiety and feel only distrust for the future.)

'I have my cock in her mouth,' I thought at a certain point... 'I have my cock in her mouth or rather she has her mouth round my cock, since it is her mouth that sought it out. I have my cock in her mouth,' I thought, 'and it isn't like other times, all those other times in recent months. As I noticed the first time I kissed her, Muriel's mouth is absorbent but not as spacious or liquid as Claire's mouth. It lacks saliva and space. She has nice lips but they're a bit thin and immobile or, rather, not immobile exactly (for they're not, I'm aware of them moving) but lacking in flexibility, rigid... While I have my cock in her mouth I can see her breasts, they are large and white with very dark nipples... her breasts are soft, like new Plasticine... I used to play with Plasticine a lot... It's incomprehensible to me that I should have my cock in her mouth...'