“Pick! Pick! Pick!

In the tunnel's endless gloom

And every blow of our strong right arm

But helps to carve our tomb.”

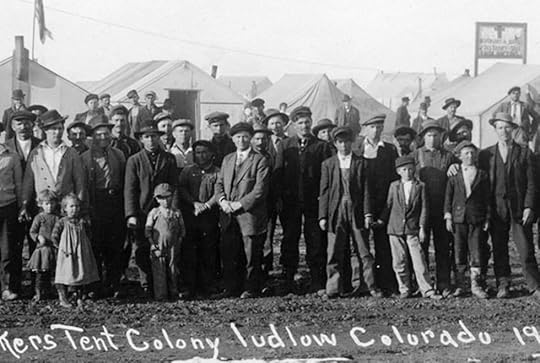

Killing for Coal provides what may be a truly unique look at, as the title goes on to say, “America's deadliest labor war,” which took place in the Colorado coal mining camps and towns in 1914. What makes Andrews' slice of U.S. history unique? The author does not limit himself to recounting the miners' strikes, the beatings, the shootings, and the incineration of women and children hiding from National Guard bullets but rather devotes the majority of his pages to examining the numerous factors setting the stage for the “war.”

The event itself has been discussed by other historians, writers, and composers. As Andrews notes, “The arch-muckraker Upton Sinclair wrote two novels about the coalfield wars. In 1946 the folksinger Woody Guthrie released his tragic lament 'The Ludlow Massacre,' which in turn inspired the people's historian Howard Zinn to write a master's thesis and several book chapters about the conflict.” What Killing for Coal brings to the table is a better understanding of how the conflict came to be, how sociological, cultural, and economic factors came into play.

Is the event itself sufficiently significant to warrant a reader's time on this 291 page book (not counting the Notes and Acknowledgments sections)? Perhaps one should spend the time reading about the United States' invasion of Mexico and occupation of Veracruz, which occupied the same timeframe, instead? After all, unless one is particularly interested in pre-WW I Colorado state history, what significance do those long-ago coalfield strikes have? As Andrews points out, “[S]ix mines, Forbes camp, and another company town lay in ruins. Upwards of thirty people had lost their lives in the Ten Days' War, the deadliest, most destructive uprising by American workers since ... the Civil War.” I admit that the time I spent in Colorado made many place names more significant than they would otherwise have been and the number of times that I passed by the CF&I steel mill in Pueblo made the actions of the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company more immediately meaningful for me; still, the history that Andrews treats has significance beyond the state borders. There is something in his book for those interested in sociology, U.S. labor movement history, social and environmental impacts of extraction industries, political power and influence, and the failure of attempted capitalistic control measures over workers. Thinking that Killing for Coal is relevant only to Colorado history would be a mistake.

One thing that I find particularly interesting is that Andrews explains the true rationale behind the creation of company towns and shows how such paternalistic beneficence was actually a means of controlling miners and of forestalling unionization. Similarly, creation of company stores and the use of scrip to pay miners created an economic peonage system from which escape was a daunting challenge. Having miners live in such company towns, also known as “closed camps,” made the task of keeping union organizers away much easier for the companies, which looked upon the United Mine Workers of America as a distinctly unsavory—or subversive—organization whose pro-worker orientation was to be avoided by all means at their disposal.

In brief, I found the content of Killing for Coal to be informative and Andrews' analysis of the sociological factors leading up to the coalfield strikes and violence to be a novel approach to the topic. Unfortunately, I also found his manner of expressing this content to approach pedantry at times. Ideas are repeated rather frequently as though the writer is hoping to expand his word count before tackling the next point. The tone of the composition, what might be termed the “voice” of the book, approaches the dry side, lacking inspiration. It simply lacks the verve that should be urging the reader to forge ahead to see what discoveries and new knowledge await in the next sentence or paragraph or chapter. Grammatically and syntactically, the writing is flawless; it's just a bit challenging to forge through at times.

Despite what I feel is sometimes a lackluster presentation, the book is well worth the time and effort to read if one has any concern or interest at all in the history of labor unrest, in the struggle of individual workers versus corporate control, and in the sociological and economic factors underlying such conflict. However, if a reader needs external motivation to forge ahead through the text, putting “Songs of the Wobblies” on the turntable may be a good idea, or at least pop over to You Tube to hear the “Colorado Strike Song” which dates from the 1914 strikes and is quoted in the book. That should get the blood stirring!