What do you think?

Rate this book

128 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1948

Et toute la nuit, dans toutes les vitrines illuminées des librairies de Paris, ses livres ouverts trois à trois veillaient comme des anges avec des ailes déployées le corps de l'écrivain défunt.

On l'enterra, mais toute la nuit funèbre, aux vitrines éclairées, ses livres, disposés trois par trois, veillaient come des anges aux ailes éployées et semblaient, pour celui qui n'était plus, le symbole de sa résurrection..

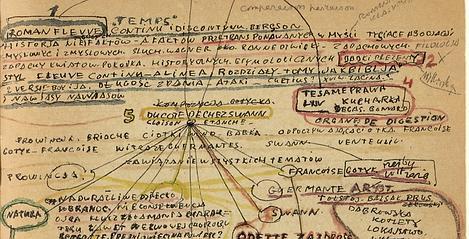

Czapski’s talks, and our knowledge of the circumstances under which they were given, have been handed down to us in this form. Further details remain difficult to verify. We know that Soviet censors monitored all public gatherings in every prison camp, disallowing the presentation of any potentially seditious (i.e. anti-communist) material. Any spoken text had to be submitted in written form for prior approval […] And we know from Czapski that this text was transcribed after the fact of his having given the lectures, not before. How was this procedural detail overcome? Over how many days or weeks did he give his lectures? How many did he give in all? “I dictated part of these lectures,” he wrote (my italics). How much more material was there in his original presentations? When were the handwritten transcriptions typed up, where, and by whom? A typewriter would not have been available to prisoners in the camp. How did these pages, in any form, manage to leave the USSR, and in whose possession? Questions pile up, one uncertainty proposing another.

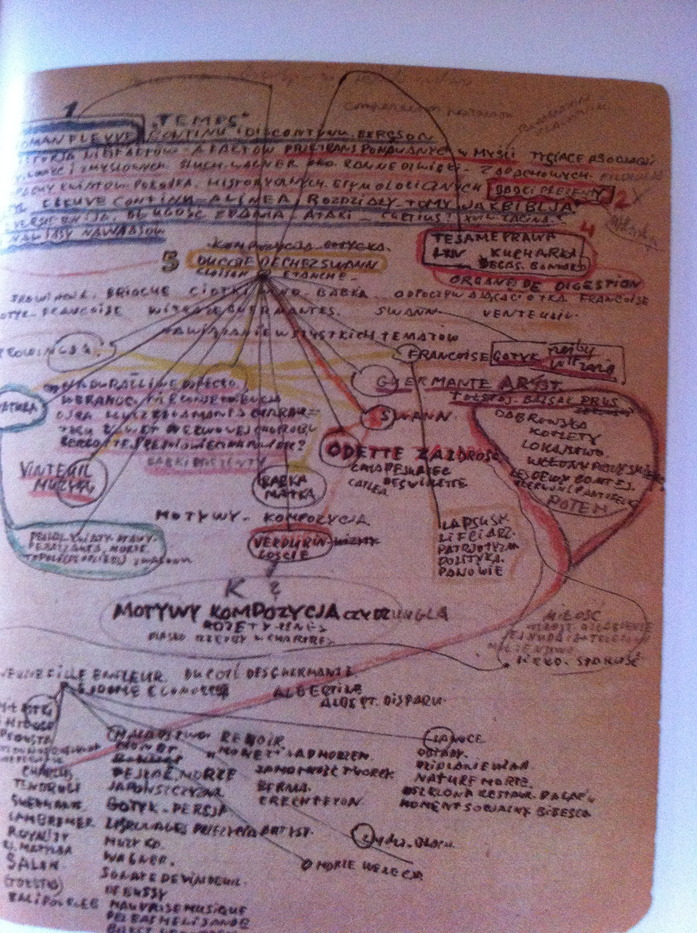

He had wanted the whole thing to appear in a single volume, without paragraphs, without margins, without sections or chapters. The prospect was seen as completely ridiculous by the most refined edtors in Paris, and as a result Proust was forced to break his book up into fifteen or sixteen sections, as each separately titled volume was broken down into two or three sections

“The joys of participating in an intellectual undertaking that gave us proof that we were still capable of thinking and reacting to matters of the mind—things then bearing no connection to our present reality—cast a rose-colored light on those hours spent in the former convent’s dining hall, that strangest of schoolrooms, where a world we had feared lost to us forever was revived.

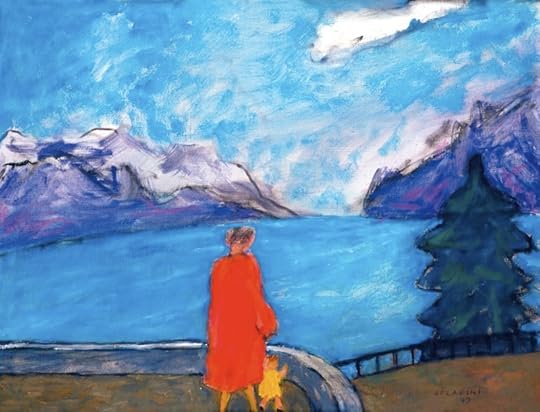

“It was incomprehensible to us why we alone, four hundred officers and soldiers, were saved out of fifteen thousand comrades who disappeared without a trace somewhere beyond the Arctic Circle, within the confines of Siberia. From those gloomy depths, the hours spent with memories of Proust, Delacroix, Degas seemed to me among the happiest of hours.”