In a year where I craved personal interactions, I have rejoined the new and improved Jewish book club. My good reads friends Jan and Stacey have done a wonderful job in running the club and choosing genres each month that they know members would be interested in reading. I honestly hadn’t thought much about the group recently other than to see what they were reading until about a month ago Jan liked my review of Man in a White Sharkskin Suit, having been lead there by good reads because she had read The Last Watchman of Old Cairo. Not to sound like a good reads ad, but I found out that Jan read the Old Cairo book as a group read in the Jewish book club. That being settled, I rejoined and feel right at home amongst members of the tribe.

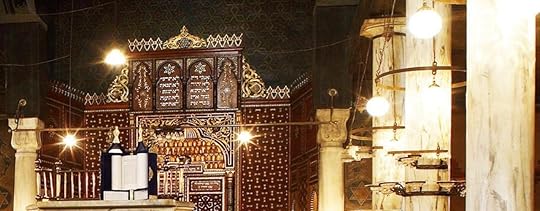

The Last Watchman of Old Cairo is the debut novel of Michael David Lukas where he tells the fictionalized story of his family history. Dating back to before the time of the Rambam (Maimonides) around 1100 C.E., an orphaned teenaged boy named Ali needed an income in order to pull his weight as a member of his uncle’s home. Having nowhere to turn to, Ali became a substitute messenger between the caliph of the palace and Shmarya the pious, leader of the Jewish community. The Jews appreciated Ali’s punctuality and offered him the position of night watchman of their synagogue, so that he could guard their precious Ezra Torah scroll as well as a geniza that dated back for centuries. Ali performed his role with the greatest of care, yet, almost cliched, he became infatuated with the daughter of Shmarya the pious, and at the urging of the elders of the congregation, got married to his cousin Fatima. Ali and Fatima would go on to have four children, and the job of watchman would be passed from father to eldest son for centuries, the family adopting the surname Al-Raqb, signifying watchman in Arabic.

Lukas moves the story to present day, which could have been his own family story. This section of the novel was written with love, and one could sense this while reading. A doctoral student named Joseph gets word that his father has died of cancer in Cairo. A few months later, Joseph receives a fragment of parchment written in both Hebrew and Arabic from a leader of Cairo’s old synagogue, which at this point is all but at extinct. In 1956, Egyptian President Abdul Nasser decreed that all foreigners had to leave the country, and this included Jews who had called Egypt home for centuries. Prior to World War II, Cairo had rivaled Paris as a jewel of a city- I got this feeling in Lucette Lagnado’s Man in a White Sharkskin Suit; yet, with the 1956 revolution and expulsion of the Jews, Cairo crumbled. Joseph’s mother’s family left for Paris even though they were Shmaryas, descendants of Shmarya the pious, and leaders of their community. Claudia was ten years old at the time and had to say goodbye to her best friend, Joseph’s father, the son of the watchman of the synagogue. The two would correspond for years, leading to a meeting a Paris, and Joseph’s birth, which Claudia kept secret until after he was born. She relocated to Los Angeles to get out from under the thumb of her parents who did not approve of Inter-religious marriages, realizing that her childhood friend was all but gone to her. Claudia would remarry a man named Bill, eliminate most religion from her life, and allow Joseph to travel to Cairo but once in his life. Upon receiving the parchment, Joseph decides to take a leave of absence from his program and spend a semester in Cairo to discover the truth of his family history.

It is apparent that Lukas did not have enough material to fill a novel with the storylines of both Joseph and Ali Al-Raqb. He added a third storyline about an expedition to recover the geniza from the old synagogue one hundred years ago. Dr Solomon Schechter from Cambridge University traveled to Cairo along with sisters Margaret Lewis and Agnes Gibson, leaders in their field of excavation. Their goal was to bring the entire geniza, highlighted by the Ezra scroll, to its new home in Cambridge. Lukas did not tend to the characters in this section with the same care as he did the ones representing his family. Dr Schechter, a leader in Jewish education, becomes a one-dimensional character with little to no role in advancing the novel. Sisters Lewis and Gibson, while ahead of their time in the 1890s, appeared to me also not as multi-faceted characters. It had been brought to my attention that Dara Horn in her Guide to the Perplexed paints a better picture of these historical figures and should be read in conjunction with this book. Perhaps one day I will because the sections here featuring the English excavation nearly made me abandon the book, as much as I enjoyed the sections featuring Ali and Joseph.

Lukas wraps up Watchman a little too neatly for my taste. The story was better than the writing, and even one third of the novel, the story line was lacking. Yet in a year like this, I have craved easy reading, neglecting most quality literary prose other than that of authors who I have previously read and enjoy. Perhaps I will one day give Michael David Lukas a second try; his other novel received awards so it at least merits a read. Or I will revisit this subject matter in Dara Horn’s book. Or I will just let it be. Reading about the rise and fall of Jews in the diaspora is always intriguing to me even though this was not Lukas’ primary aim in this book. This is a book I’m certain I would not have read if it had not been for good reads. I am glad that I rejoined the Jewish book club and have a home for all the Jewish themed books that I have been reading on my own over these last few years. I have a feeling that regardless of the quality of the books chosen, there is certain to be a great discussion afterward.

3 stars