The main argument of this book that the human ability to reason is evolutionary evolved not to support individual cognitive decision making, but as a tool to justify intuitive decisions to the others. 400 pages are following to justify that hypotheses to us. It has only partly convinced me, but it was interesting to read. The results of a few experiments they described I found puzzling as my own "result" was different from the "majority" almost always. In general, I think I am taking a break from evolutionary psychology until it develops little further.

Below are the excerpts and quotes I found insightful:

"What functions does the reason module fulfill? We have rejected the intellectualist view that reason evolved to help individuals draw better inferences, acquire greater knowledge, and make better decisions. We favor an interactionist approach to reason. Reason, we will argue, evolved as a response to problems encountered in social interaction rather than in solitary thinking. Reason fulfills two main functions. One function helps solve a major problem of coordination by producing justifications. The other function helps solve a major problem of communication by producing arguments. (Our earlier work has been focused on reasoning and on developing, within the interactionist approach, an “argumentative theory of reasoning.”)"

" When beliefs are not readily testable, it is quite rational to accept them on the basis of trust, and it is quite rational for people who trust different authorities to stubbornly disagree. We don’t mean that these are the most rational attitudes possible. An intellectually more demanding approach asks for clarity and for a willingness to revise one’s idea in the light of evidence and dissenting arguments. This approach, which has become more common with the development of the sciences, is epistemically preferable—but no one has the time and resources to apply it to every topic."

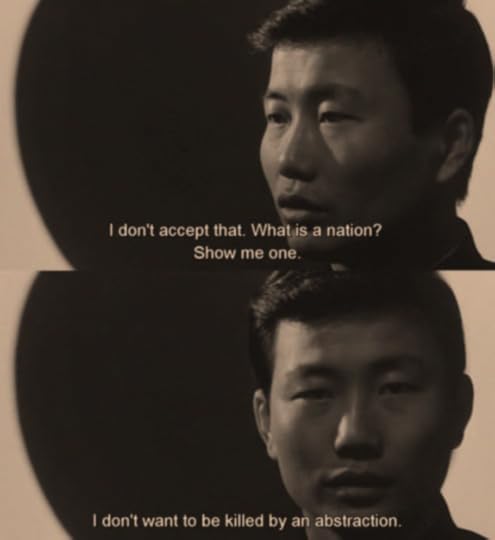

"Reasons are social constructs. They are constructed by distorting and simplifying our understanding of mental states and of their causal role and by injecting into it a strong dose of normativity. Invocations and evaluations of reasons are contributions to a negotiated record of individuals’ ideas, actions, responsibilities, and commitments. This partly consensual, partly contested social record of who thinks what and who did what for which reasons plays a central role in guiding cooperative or antagonistic interactions, in influencing reputations, and in stabilizing social norms. Reasons are primarily for social consumption."

"Rules of arithmetic are taught and are not contested. There is no agreement, on the other hand, on the content and very existence of rules of reasoning. What is sometimes taught as rules of reasoning is either elementary logic or questionable advice for would-be good thinking or good argumentation (such as lists of fallacies to avoid, which are themselves fallacious)."

"When people reason on moral, social, political, or philosophical questions, they rarely if ever come to universal agreement. They may each think that there is a true answer to these general questions, an answer that every competent reasoner should recognize. They may think that people who disagree with them are, if not in bad faith, then irrational. But how rational is it to think that only you and the people who agree with you are rational? Much more plausible is the conclusion that reasoning, however good, however rational, does not reliably secure convergence of ideas. Scientists, it is true, do achieve some serious and, over time, increasing degree of convergence. This may be due in part to the many carefully developed methods that play a major role in conducting and evaluating scientific research. There are no instructions, however, for making discoveries or for achieving breakthroughs. Judging from scientists’ own accounts, major advances result from hunches that are then developed and fine-tuned in the process of searching, through backward inference, for confirming arguments and evidence while fending off and undermining counterarguments from competitors."

"Communication is a special form of cooperation. The evolution of cooperation in general poses, as we saw in Chapter 9, well-known problems. It might seem reasonable to expect that theories that explain the evolution of human cooperation might also explain the evolution of communication.14 Do they really? Actually, communication is a very special case. In most standard forms of cooperation, cheating may be advantageous provided one can get away with it. For any given individual, doing fewer house chores, loafing at work, or cheating on taxes, for example, may, if undetected, lower the costs of cooperation without compromising its benefits. This being so, cooperation can evolve and endure only in certain conditions—in particular, when organized surveillance and sanctions make cheating, on average, costly rather than profitable, or when the flow of information in society is such that cheaters put at risk their reputation and future opportunities of cooperation. For communication to evolve, however, the conditions that must be fulfilled differ considerably from this. Although this is hard to measure and to test, there are reasons to think that communicators are spontaneously honest much of the time, even when they could easily get away with some degree of dishonesty. Why? Because when humans communicate, doing so honestly is, quite commonly, useful or even necessary to achieve their goal. People communicate to coordinate with others, to organize joint action, to ask help from friends who are happy to give it. In such situations, deceiving one’s interlocutors, even if undetected, wouldn’t be beneficial; it would just be dumb. Still, in other situations that are also rather common, a degree of deception may be advantageous. People generally try to give a good image of themselves. For this, even people who consider themselves quite honest routinely exaggerate their virtues and achievements, use disingenuous excuses for their failings, make promises they are not sure to keep, and so on."

"The message of this chapter might seem bleak. Reason improves our social standing rather than leading us to intrinsically better decisions. And even when it leads us to better decisions, it’s mostly because we happen to be in a community that favors the right type of decisions on the issue. This, however, cannot be the whole picture. Justifications in terms of reasons do indeed involve deference to common wisdom or to experts. What implicitly justifies this deference, however, is the presumption that the community or the experts are better at producing good reasons. But there is a potential for tension between the lazy justification provided by socially recognized “good reasons” and an individual effort to better understand and evaluate these reasons, to acquire some expertise oneself."