Has it been a decade already? Book five of The Complete Peanuts, which includes every strip from 1959 and 1960, marks the franchise's tenth anniversary. It's hard to believe that by the time Bill Watterson's Calvin and Hobbes notched ten years, it was at its end; Peanuts still had another forty to go. January 2, 1959 gets the year off to a fast start as Lucy presents her friends with lists of character faults they should eliminate in the coming year. Lucy has "high ideals," she explains to Charlie Brown. "I want to make this a better world for me to live in!" It always feels more gratifying to dissect and condemn other people's flaws than our own. January 12 (page six) is a nice strip: Violet says something insulting about dogs, and when Charlie Brown speaks up on their behalf, Snoopy's gratitude is heartfelt...if a bit clingy, as we observe the rest of the week. By 1959 Patty was less integral to Peanuts than she used to be, but on January 24 (page ten) she and Charlie Brown have an enlightening philosophical conversation. She assures him that everyone has good and bad days, but Charlie Brown counters that "Last year I was the only person I know who had three hundred and sixty-five bad days!" Negative experiences stand out in the mind more than good ones, so we tend to forget the good happened at all. A lot of Charlie Brown's depression stems from this.

January 26 (page twelve), Charlie Brown writes to his penpal, a strip that ends with a witty punchline about spelling. Charles Schulz is a master of pithy comedy. On February 9 (page eighteen), Lucy uses her watch to count aloud as Charlie Brown ages, second by second. It's disconcerting to think about time ticking by, rather than focus on filling it with worthwhile activity. Charlie Brown engages in another smart discussion with Patty on February 25 (page twenty-four), telling her that arithmetic is a bad subject for him in school. "I'm at my best in something where the answers are mostly a matter of opinion!" The artist in each of us empathizes with that statement; trying to create beauty is very different from having to arrive at objectively correct answers. March 13 (page thirty-one) caps off a week of Charlie Brown fretting about a library book he lost. Plagued by anxiety over how the library will react, Charlie Brown goes wildly giddy with relief when he locates the book before the day of reckoning. Linus's comment: "In all this world there is nothing more inspiring than the sight of someone who has just been taken off the hook!" Aye, being "shot at and missed" is an unrivaled euphoria. Sunday, March 22 (page thirty-five), Linus builds a fantastically elaborate sandcastle, but heavy rain washes it away. Linus puzzles over the moral to his story, but I think it's this: before you pour your heart and soul into creation, be sure the investment is in something likely to last. Castles of sand inevitably disintegrate.

Here we go! March 27 (page thirty-seven) is the beginning of an era as Lucy sets up her "Psychiatric Help 5¢" booth and delivers her first pitiless advice to Charlie Brown. The bit would remain a Peanuts mainstay for decades. On March 30 (page thirty-nine) Snoopy reminisces about a time when a girl walked by and shared her ice-cream cone with him. When Lucy happens by the same spot in the present day, she's less charitable, and a disappointed Snoopy thinks, "You can't go home again." The places where we had our greatest days feel almost magical, as though good things are waiting to come our way again in that exact spot, but rarely is fate so kind. Charlie Brown and Lucy talk social politics on April 10 (page forty-three). He mentions an article that says today's young people don't believe in any causes, and Lucy loudly objects: "I'm my own cause!" Her stance seems a silly one to take, but it's quite prevalent. Societies decline when we get so wrapped up in our own identities that we lose the vision and verve to promote causes beyond ourselves. May 15 (page fifty-eight) is a return to pure humor, as Charlie Brown reads a scary story to Linus. Snoopy's impression of a vampire bat when a nervous Linus turns to look at him is excellent visual comedy. A story arc that changes Peanuts forever commences May 25 (page sixty-three) when Charlie Brown remarks that his mother will be at the hospital for "about five days." Could it be...? Yes! May 26 confirms that Charlie Brown has a baby sister, and June 2 (page sixty-six), her name is given for the first time: Sally. Peanuts will never be the same.

One of the funniest Sundays in this collection is June 14 (page seventy-one). Lucy attaches a bell to Snoopy's collar, but he's not used to the way it jingles when he trots around. Snoopy delivers the perfect punchline, in a single word. June 28 (page seventy-seven) is another good Sunday. Linus offers to share his ice cream with Snoopy, and Lucy throws a fit. Doesn't he know dogs have filthy mouths? Snoopy walks off feeling downcast and degraded. "I'm less than human!" Even people can feel that way, when others dehumanize us for personal traits they object to. It's a lonely, helpless feeling, and most of us can identify with Snoopy's dejection. July 1 (page seventy-eight), it dawns on Charlie Brown that his new sister isn't the life-changer he expected her to be. He adores Sally, but depression still overtakes him at times, and he doesn't feel that most people like him. Punctuated by Linus's poignant final line, this is one of the most famous strips Charles Schulz wrote, finding its way into A Charlie Brown Christmas, the classic 1965 television special. July 30 (page ninety-one) is a spiffy little insight into the human condition. Linus tells Charlie Brown he wants to develop concern for others; those more fortunate than himself, not less. "I want to bring them down to my level!" Such is the politics of envy, an outgrowth of warped human nature. We'd rather have no one do well than see anybody prosper more than ourselves. August 1 is an expansion on this point; Linus declares he wants to be a great philanthropist, but when Charlie Brown points out that it requires wealth, Linus amends his statement. "I want to be a great philanthropist with someone else's money!" Isn't that always the way? Distributing somebody else's cash is fun, but it's another thing entirely when the money represents your own blood, sweat, and tears. If generosity were easy, everyone would take part.

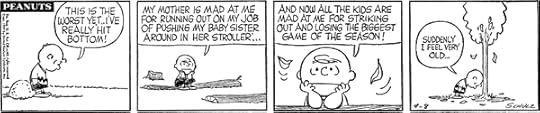

August 23 (page one hundred one) is a historic day: the first appearance of Sally Brown, being pushed in a stroller by her brother. September 9 (page one hundred eight), Charlie Brown is discouraged that everyone is mad at him. He feels ill-equipped to deal with life: "I think the whole trouble is that we're thrown into life too fast...we're not really prepared." We only get one shot at life, so what hope is there of doing it right? Our time on earth is at least as defined by our mistakes as our triumphs, and we have to make peace with that or we'll never be happy. October 5 (page one hundred twenty) introduces Miss Othmar, the teacher Linus has fallen in love with. The next two weeks revolve around his crush on her, providing much of the material for the 1975 television special, Be My Valentine, Charlie Brown. October 22 (page one hundred twenty-seven) is a cute, wordless strip involving Snoopy, Sally, and a game of "Spin the Bottle." If this one doesn't coax a smile, I don't know what will. Snoopy wrestles with existential dread on October 24, alone in his doghouse at night. What is life's purpose? The last panel is an honest, earnest admission by our favorite beagle: "I haven't got the slightest idea!" Confident as we may be in our worldview, no one is certain what lies over the final horizon. Another storyline that finds its way into a television special begins October 26 (page one hundred twenty-nine), with Linus writing a letter to the "Great Pumpkin." Oh, what fun this time of year is in the world of Peanuts. Debuting in 1966, It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown is arguably the most charming television special Charles Schulz wrote. Some of its memorable lines derive from this week of October 26, 1959, particularly the October 30 and 31 strips.

Though it's not Christmas themed, November 26 (page one hundred forty-two) is quoted in A Charlie Brown Christmas. Charlie Brown suggests "Pig-Pen" might have on him the dirt and dust of ancient civilizations; maybe he's not just a slob. Christmas is in full gear by December 20 (page one hundred fifty-two), as Linus finishes dressing for the pageant and rehearses his lines. The climactic scene from A Charlie Brown Christmas is based on this storyline. December 24 (page one hundred fifty-four) is a cheerful holiday strip, Linus watching the snowfall through a window and announcing "It's pitch white outside!" I love his way with words. The Christmas special again finds source material January 5, 1960 (page one hundred fifty-nine), Linus catching snowflakes on his tongue and Lucy saying they're not ready to eat at this time of year. The timeline Lucy gives differs from that in the special, but Linus's punchline is the same: "They sure look ripe to me!" Charlie Brown talks at length on January 20 (page one hundred sixty-five) about people not liking him, explaining why he feels uncomfortable no matter what size group he's in. When your commentary is drenched in negativity, you don't present yourself as pleasant company, Charlie Brown discovers. March 20 (page one hundred ninety-one) is pure cuteness, the first time Linus spends quality time with baby Sally. Charlie Brown might not approve of him coaching her on how to suck her thumb and cling to a security blanket, but the strip is as charming as Peanuts ever gets. We see perhaps the most famous comic of Charles Schulz's career on April 25 (page two hundred seven). All that needs to be said: "Happiness is a warm puppy." May 30 (page two hundred twenty-two) is a smart insight, as Lucy tells Linus not to throw away her birthday card from Charlie Brown. She's a sentimental person, she informs her brother. "I'll save it for a little while, and throw it away tomorrow!" That's worth a chuckle, but also reveals how most of us truly feel about these things. After a short time we forget why we valued our sentimental keepsakes and then toss them out without another thought. We're more like Lucy here than we care to admit.

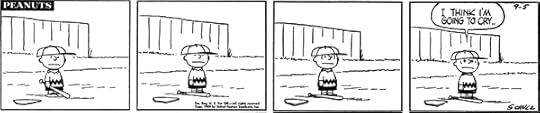

Winsome humor is a Charles Schulz specialty, and June 5 (page two hundred twenty-four) is a prime example. How could Linus and Snoopy resist breaking into a song and dance number when they start connecting the bones of a dinosaur skeleton model? "Oh, the ankle bone connects to the leg bone..." Lucy isn't amused, but I love it. In early July, Lucy benignly picks on Charlie Brown for having a "failure face." Her closeup examination and explanation of its features to Linus on July 1 (page two hundred thirty-five) is hilarious. August 10 (page two hundred fifty-two) sees Charlie Brown under pressure on the pitcher's mound. If he can notch one more out, his team will somehow win this baseball game, and every player on his squad has advice regarding pitch selection. In life, everyone seems to have an opinion on how you should comport yourself, but as the saying goes, "too many cooks spoil the broth." You have to tune out the noise and make your own decisions, for better or worse. Sunday, August 21 (page two hundred fifty-seven) is vintage Peanuts comedy, Linus shouting at the rain to leave so the team can play baseball. When the downpour abruptly stops, he's spooked by his own power. August 22 (page two hundred fifty-eight) kicks off a major storyline. It's the first time Sally walks, and the first indication she's enamored of Linus. As her feelings deepen, so does his discomfiture; the narrative is two weeks of emotional ups and downs. September 1 (page two hundred sixty-two) may be the pinnacle of the arc, perfectly portraying the emotional extremes of love.

Lucy scolds Snoopy for following her around on September 18 (page two hundred sixty-nine). His confidence is shaken—do all the kids view him as a pest?—but some timely affection from Violet remedies this. A friendly face and a few kind words are often all that's needed to heal a wounded heart. An extended story about the freeway commission planning to bulldoze Snoopy's doghouse to build a road ends September 26 (page two hundred seventy-three)...for now. The work is postponed until 1967, but will the issue resurface at that point in Peanuts history? I'm curious to find out in book nine of this series. Halloween of 1959 laid a firm foundation for It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown, but Sunday, October 30 (page two hundred eighty-seven) of 1960 provides the climax for the special, as Linus and Charlie Brown wait in the pumpkin patch for the "Great Pumpkin." Is that truly him rising among the gourds under the full moon? November 18 (page two hundred ninety-five), Lucy and Linus marvel over what appears to be a butterfly migrated up from South America. Or...is it a potato chip? Lucy's punchline is terrific. November 21 (page two hundred ninety-seven), Snoopy wistfully ponders the birds, gone south for winter. They're usually an annoyance, but the scene feels unnaturally silent without them. When it comes to family, friends, or even people we don't much like, we fail to realize what they mean to us until they're gone. The quiet is unsettling without them to fill it. It's another quirk of human (or beagle) behavior that Charles Schulz captures as deftly as any cartoonist who ever lived.

Reading the fifty-year Peanuts series from start to finish is a joy. I love the effervescence and moodiness of the strip; the television specials, too, all written by Charles Schulz himself through 1994. His devotion to Charlie Brown and the gang bleeds through in every stroke of artistic design, in every wise, emotional, or sweet saying uttered by his characters. The 1960s is said to be Peanuts in its prime, and book five indicates things are headed that way. I'd say it's the best two years from the first decade of the strip. If better is yet to come, I'm excited for it.