The title says it all – the TRUE History. The adage is – history is told from the viewpoint of the victors. If this is the case, then the Kellys of Benalla should not be the mythologised folk that they are. Their story is a complicated one, and one that has been very much forgotten in recent decades: the denigration of Irish Catholics in Australia. I also suspect it was by these same Irish Catholic immigrants and descendants that helped create the myths. The myth however, particularly up to the 1980s has Kelly as a misguided and wronged hero fighting the system. I have always argued that point being quite romantic and not honest to the complex man.

Carey uses this very famous story and tells it from the point of view of Ned Kelly. It is described as various notebooks, exercise books, loose leaf sheets, and deliciously, the letterhead paper from the Bank of New South Wales in Jerilderie. It is Ned’s memoir and confession – although that word is being used in a rather cavalier way.

The major theme here is the poor treatment of the Irish Catholics by the English, and for me, worst still, by those Irish that have come to a position of power or wealth. It is easy to forget the prejudices that British migrants brought with them to Australia, but it was very real. Ruth Park’s Harp in the South deals with poverty in inner Sydney and being poor Irish Catholic. Other places where it is still observable is the resultant different gauges of rail network between the colonies/ states; and all due to the engineers coming from separate countries and having biases towards nationality. In Carey’s novel we observe police brutality and abuse of power. Ugliest of all is the disregard of the virtue of the young women: Ned’s sisters are exposed to revolting sexual advances from the men. Being Irish and Catholic, these women are regarded as little more than free whores, and with all the consequences of the result of what one would regard as the fallen woman of the Victorian period. Carey explores the essence of family, and of friendships of young men. This is quite important, and it is good to remember that the prison system at that time was full of Irish men. Essentially, it was a breeding ground for dissent and alliances; probably not quite what the English had in mind when they locked them up.

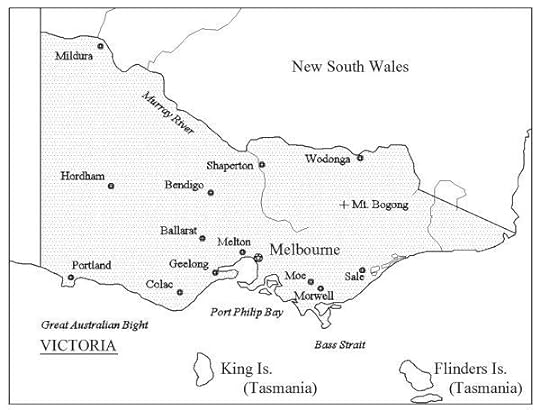

In truth, the pressures put upon the poor Irish Catholics such as the bigotry, the difficulty in advancing out of poverty, and the resentment that built up, it isn’t surprising that Ned Kelly, a fiery hothead, would take to petty crime. It is very important to see who the Kellys targeted: people who they felt wronged them, the establishment ie: Bank of New South Wales, and the police. How they treat people during the siege at Jerilderie shows they were not completely ruthless. I suspect it was the tales told after here & in Euroa that their support base developed.

I don’t romanticise Kelly’s actions, and neither does Carey. There is wit, and humour throughout the novel, along with well thought out humanity. None of the characters are cardboard figures; all are well fleshed, and even our narrator, Kelly himself, manages to give us an insight into his vitality, humour, and humanity. It’s what I liked most about this novel, and this is Carey’s strength in that he was able to create and develop this based on his reading of the Jerilderie Letter. Carey records and comments on the pettiness and gossip associated with regional centres and towns; I’ve noted in previous novels that he does this well (ie Illywacker).

The clever aspect of this novel is the lacunae in the narrative. Carey does this well implying sheets or books are missing. Conveniently, of course, they are at moments in the Kelly history when Kelly’s actions are not chivalric or laudable. For example, as when Kelly stole horses as part of the Greta mob, or later with the assassination of Aaron Sherritt. Although we do see the kind and loving side of Kelly, he is also a product of a series of incidents and actions of outsiders, including his father being a convict (and thus “obvious” going to produce troublesome children), that lead to him being angry and petulant about his lot in life; how he is downtrodden and hard done by. These periods of the book definitely do not make the reader love the narrator/ hero. Again, I feel Carey carries this out well, honestly, and makes for a better reading experience.

Carey has lots of clever moments that makes the informed reader smile, but which would make the novice completely gloss over or ignore. For me, that would be a shame, as these “easter eggs” made the reading so much more enjoyable. The best example is the use of Bank of New South Wales letterhead with the word Jerilderie on it. Of course, Carey is making a nod to the important Jerilderie Letter that Kelly dictated – all 50 odd pages. Carey read this, and used this as the basis for the novel; he was able to read the voice and use it expertly in the drawing and creating of his own character, and in the style of the whole novel. It is touches like this that reveal the expertise and calibre of Carey’s skill as a novelist.

Thus, Yes! I would recommend this to others, but I would be wary to do so to any that aren’t familiar with the Kelly story. For those, go read the Wikipedia synopsis and then read this book with delight.

I seem to like the idea of Peter Carey rather than results, and have some flisters that I'm in awe of who really rate Carey's work.

I seem to like the idea of Peter Carey rather than results, and have some flisters that I'm in awe of who really rate Carey's work.