What do you think?

Rate this book

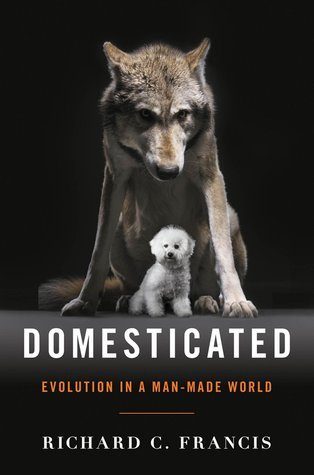

496 pages, Hardcover

First published May 25, 2015

Virtually all purebred dogs have a host of genetic ailments, from narcolepsy to skeletal defects. Cancer is also rampant among purebred dogs, occurring at frequencies that in humans would be considered epidemic. Any account of a breed’s characteristics includes the defects, including the particular form of cancer, to which it is prone. This is why purebred dogs have much shorter life spans than outbred dogs (mutts and mongrels) living under the same conditions.What do you want a dog for, it's beautiful looks or a loving companion? Too many people want the beautiful animal with the a guaranteed temperament. More people should be willing to take a chance and get a dog or puppy that needs a home. They will be your companion for many more years.

This genetic burden may also help explain why dog breeds are exceptions to what is otherwise the rule among mammals: larger species live longer than smaller species. Elephants live longer than cats, which live longer than mice, and so on. Among dogs, however, large breeds die younger.87 Irish wolfhounds, Great Danes, and Newfoundlands live only 6–8 years; dogs in the 50-pound range generally live 10–12 years; some toy breeds live 15–20 years.The book is in part very heavy on the science and completely mystifies me, "The genetic changes resulting from both the Baldwin effect [the premise that phenotypic plasticity is the way for individuals to adapt to their environment within a generation in a novel environment] and genetic assimilation are facilitated by disruptive selection and the cryptic genetic variation it unveils."