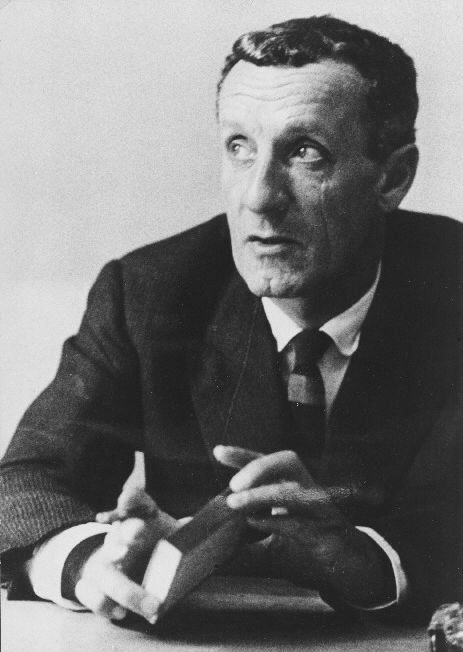

These seven talks, originally broadcasted on the radio by Merleau-Ponty in october and november 1948, are generally considered to be a (very general) introduction to his philosophy of perception. The talks themselves are all rather short with some of them more than half filled with examples and illustrations - albeit very intriguing ones.

Merleau-Ponty's main thesis is very easy to grasp.

He thought, wrote and published in the era when classical science was overthrown with relativity and quantum mechanics, and when philosophy was radically re-oriënted - on the continent towards phenomenology (Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre, etc.) and overseas towards logic and linquistics (Russell, Wittgenstein, etc.). During the same time, art was radically re-defined. Gone were the objective representations of things, people and events, to make room for impressionism, expressivism and surrealism. In short: the old way of looking at the world was being replaced by a new way of looking at the world.

What changed?

Classical thought aimed at establishing systems of absolute, certain knowledge - with Descartes and Newton being typical examples. This was all replaced with modern physics, when humanity learned that nature is at its core uncertain, ambiguous and relative. A similar line of development is seen in the life sciences, with the dynamism of evolutionary change replacing the Aristotelean or Biblical essentialism of species. Notions like space, time, and indeed all aspects of human nature, were now seen in a new light - or rather in an amalgam of many, many new lights.

Nietzsche already foresaw this with his perspectivism, while Husserl already developed a method with which to methodically study all aspects of human nature in a new, phenomenological way. Heidegger then shifted Husserl's focus on pure (inner) consciousness towards human nature in its general existence. And along comes Merleau-Ponty, who develops Heidegger's ideas into a bodily theory of perception.

That is, according to Merleau Ponty, all art, knowledge and action (i.e. aethetics, science, ethics) is founded on human perception. First, we are confronted with others in the world. This confrontation makes us aware of our own feelings, motivations, intentions, etc. as well as attributing these to other people. In other words: we first and foremost exist as subjects in relation to other subjects (as objects), and it is both these relations and the objects themselves which perception is concerned with.

Merleau-Ponty's claim is that our bodies fulfil a crucial role - we perceive through our bodies, perceptions do not exist in a pure form - like Descartes and people after them claimed. Whence does this illusion come from? Well, we become aware of other people and things, and we start to reflect on our relationship to those people and things, in all their aspects. Out of this reflection is born our self-consciousness. This Ego is not an entity, a Cartesian 'ghost in the machine', an immaterial soul steering our material body - it simply is the product of our mind reflecting on our perceptions.

Classical thinkers - both philosophers and scientists - started from this Ego and then attempted to establish it, somehow someway, as the foundation of knowledge. Cf. Descartes, Locke, Kant, Husserl, etc.

The reality is that we simply perceive things and people, and this is a process, not a simple act. This means that what we perceive and how we become aware of these aspects, is intrinsically connected to our bodily relationship with these objects. And this means that we can perceive any object in any kind of way. When I look at a table, the table is not a thing-in-itself, an unknowable object as cause of all its appearances (colors, texture, etc.). No, this table is the collection of all my perspectives on this table - and these perspectives in their turn are relationships between my body and this table. For example, when I think about how this table resists gravity it will determine my particular perspective on this table, while this perspective is still one of the many (infinite?) possible perspectives I could take.

With this theory of perception, Merleau-Ponty is able to cut the Gordian knot that ties empricism and rationalism together. This age old debate is senseless. The rationalist claims his knowledge of the mentioned table derives from a priori structures in his consciousness, while the empiricist claims his knowledge of the mentioned table derives from an un-knowable object an-sich that causes all the appearances of this table. Both are wrong - they both overlook the fact that they already assume (!) the perception of the table. That is, both empiricism and rationalism attempt to explain how a perception is caused, but they fail to ask the prior question about the perception itself.

Merleau-Ponty claims we perceive the world, first and foremost, and only afterwards start to rationalize. These attempts have failed. Just like an artwork offers the spectator a world, to perceive in all its aspects, so does nature offer the scientist a world, to perceive in all its aspects. There is no absolute knowledge, just like there is no absolute space.

The final paragraphs of this little book are interesting, since Merleau-Ponty here ponders how it is that this post-modern phase is only now (1940's France) arising. He concludes that while it might be due to "the honest awareness of this culture" that we acknowledge the uncertainty in the world, it is more likely that this uncertain and unfinished state of affairs has always been with us. According to him, people like Da Vinci and Balzac left many unfinished works, yet we perceive these classical geniuses to be complete, to be whole. This might be simply a "retrospective illusion".

He mentions that objectivity is not possible. The scholar brings his own preconceived notions to his observations and reports. E.g. the historian has to select what he writes down, how he writes it, even the order and internal structure. All these choices are fueled by his culture, education, language, etc. This means that any work in history is intimately tied to the scholar who wrote it down. In a similar vein, any observer in any location in space-time, will have his own frame of reference - there is no absolute, objective space (à la Newton).

Although I have more to read from Merleau-Ponty to really offer any serious insight on these affairs, I do think he has a point. Socrates - generally considered to be the (if not one of the) founder(s) of philosophy - is mostly remember for his way of questioning people. Most of the Socratic dialogues end in aporia's. That is, Socrates, as prototype of the artist-philosopher, was looking for knowledge, yet had an "honest awareness" of the uncertainty of all knowledge claims. Perhaps it is just the human mind that impresses its hunger for certainty and completeness on the world.

I do wonder, though, if this does not mean the breakdown of any pursuit of knowledge whatsoever. If all there is are personal perceptions, arising from our bodily relationships to objects; and all we can do is try to learn the (many, many) perspectives of others; where does this leave room for any meaningful insights? For example, how do we know relativity theory is true?

I am reading Merleau-Ponty's Phenomenology of Perception next - I hope to get some answers from that work...