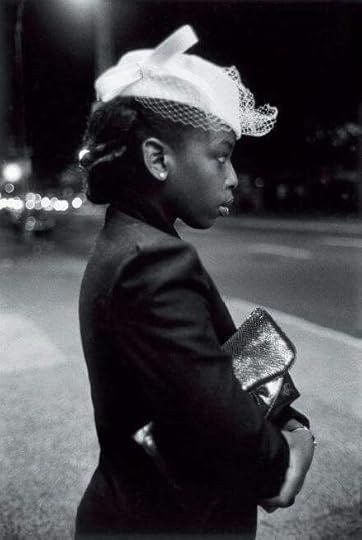

I think Maud Martha would approve of this edition of her book, which is spaciously printed in an elegant font on thick, smooth paper. One of the most touching things about her is her love of beauty and fineness and pleasantness in things. After her marriage, she misses the seasonal rituals of her family home:

And birthdays, with their pink and white cakes and candles, strawberry ice cream, and presents wrapped up carefully and tied with wide ribbons: whereas here was this man, who never considered giving his own mother a birthday bouquet, and dropped into his wife's lap a birthday box of drugstore candy (when he thought of it) wrapped in the drugstore green

It's the little sugar in the bowl that makes life sweet, not lavish spending, that she wants. Maud Martha reminds us that dandelions are embellishment, can give pleasure. She wants to be cherished, like her sister Helen, whose name, of course, suggests someone who inspires extravagant tribute. Helen has grace, but in Maud Martha's eyes, little else to justify the way she is seemingly adored over herself. The author takes a kind of revenge:

“You'll never get a boy friend,” said Helen, fluffing on her Golden Peacock powder, “if you don't stop reading those books”

If there's no love for reading girls (because we're dangerous), then the world is wrong, we know absolutely, cuddling our books for comfort.

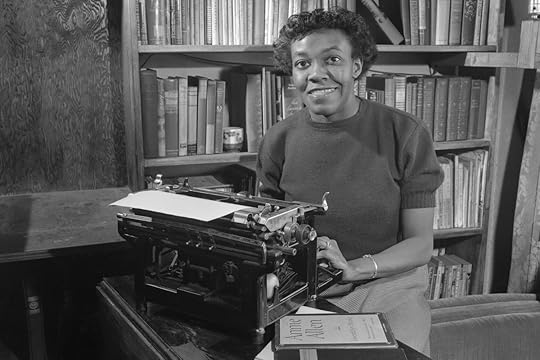

What she wanted was to donate to the world a good Maud Martha. That was the offering, the bit of art, that could not come from any other. She would polish and hone that.

I liked her first beau, 'decorated inside and out', not so much the second who, longing for beauty and elevation like Maud Martha, fails to find any hope of it in black life. Years after Maud Martha has married someone else, he meets her at a university where they're watching a young black writer speak, and she witnesses him fawning over white friends, shrugging her off as she crimps his style. It's his problem, but another part of it is hers, like when she envies a lighter-skinned woman, 'Gold Spangles' who dances with her husband, Paul.

'It's my color' she thinks, that makes Paul mad, 'what I am inside, what is really me, he likes okay. But he keeps looking at my color, which is like a wall. He has to jump over it in order to meet and touch what I've got for him. He has to jump up high in order to see it. He gets awful tired of all that jumping.'

Poor housing blights Maud Martha and Paul; they live in a kitchenette and have to share a bathroom. Maud Martha's own story tells so much on how it is in so few words, but when she describes her neighbours in 'kitchenette folks', the text's density multiplies as more windows are deftly flung open on lives rubbing along, more or less discontentedly. Hope shines in the romance of 'the Whitestripes' who adore each other, but the hope that isn't for you perhaps hurts more; Paul admonishes her for admiring the couple: 'you can stop mooning. I'll never be a 'Coopie' Whitestripe.' Maud Martha agrees.

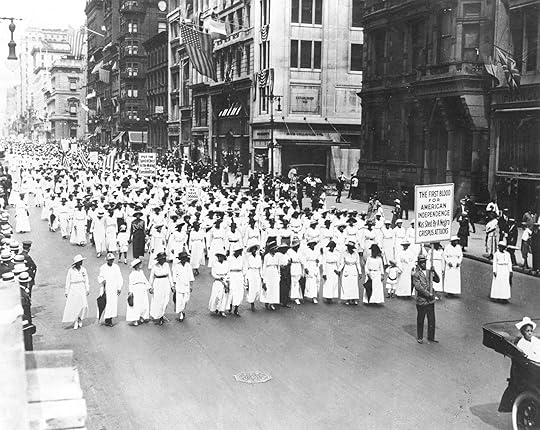

The cruelty, meanness, and racism of white folks occasionally pokes into Maud Martha's life, precipitating more horizontal violence (her conversation with the beautician who tells Maud Martha she didn't pull up the white saleswoman on her offensive language because she thinks they, black folks, should be less sensitive) and hard work for Maud Martha (reassuring her daughter that Santa loves her and promising her gifts to prove it after a constumed Santa in a toy store is rude and perfunctory to her). Brooks shows that black people always have to do the heavy lifting of race. Perhaps most incisive is the episode 'At the Burns-Coopers' where Maud Martha takes on work as a 'housemaid' and after one day of listening to the Mrs go on about her expensive pleasures knows she won't come back, despite the good wages:

Shall I mention, considered Maud Martha, my own social triumphs, my own education, my travels to Gary and Milwaukee and Columbus, Ohio? Shall I mention my collection of pink satin bras? She decided against it.

Because Mrs Burns-Coopers, we can see, would not know how to respond, because she cannot imagine that Maud Martha has a life and a mind.

Veg*n thoughts: a chapter about the struggle and horror of preparing the corpse of a hen to eat is entitled 'brotherly love'

And yet the chicken was a sort of person, a respectable individual, with its own kind of dignity. The difference was in the knowing. What was unreal to you, you could deal with violently. If chickens were ever to be safe, people would have to live with them, and know them, see them loving their children, finishing the evening meal, arranging jealousy.

This passage relates back to Maud Martha's empathy with the mouse she caught much earlier in the book, and the elation and surprised pride she felt when she released the creature telling her to 'go home to your family'. It also relates, I think, to the way white folks behave, in their failure to see black folks as fully human.

I could never forget that this is a poet's book. Each line walks to the corner, turns with a flourish like a dancer, a fineness and exactness that catches breath. It is an epic in vignettes, radiating truth like sunlight.