What do you think?

Rate this book

416 pages, Kindle Edition

First published January 1, 2005

. . . the reader who picks up this book looking for a definitive pronouncement as to whether “the South” still exists as a distinctive region is destined to put it down disappointed. . . . I hasten to point out that what I am offering here is a history rather than the history of southern identity. I make no claim that what I have done is totally inclusive or definitive. On the other hand, I do believe this book offers a useful chronologically comprehensive historical framework for understanding the origins and evolution of an ongoing effort, now into its third century, to come to terms with the South’s role as both a real and imagined cultural entity separate and distinct from the rest of the country. Because southern distinctiveness has so often been defined in opposition to our larger national self-image, this enduring struggle with southern identity has actually become not only a sustaining component of southern identity itself, but as we shall see, of American identity as well.

In the 1830s writers eager to explain why the inhabitants of the northern states and those of the southern states appeared to be so different in values and temperament had begun to seize on the idea that the people of the two regions were simply heirs to the dramatically different class, religious, cultural, and political traditions delineated by the English Civil War. The northern states were populated, so many believed, by the descendants of the middle-class Puritan “Roundheads” who had routed the defenders of the monarchy, the aristocratic Cavaliers, supposedly of Norman descent, who had then settled in the southern states.

I expected Dr. Cobb to be a cogent, story telling Southerner. What I got was dry, repetitive, incomplete, and a jumble of facts flying fast and furiously.

. . .

Bottom line, Cobb presents little that is positive about the South.

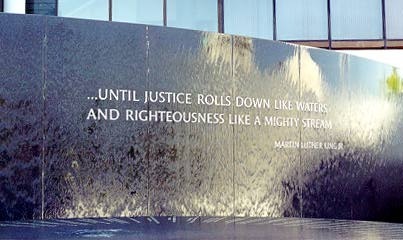

After four years of common struggle against the North, they not only responded to the term “Southern” with an emotion once reserved for Virginia or Carolina or Georgia, but they were much more acutely conscious “of the line that divided what was Southern from what was not.”

. . .

…”the South was born for a great many white Southerners not in Montgomery or even in Charleston harbor, but, as Robert Penn Warren observed, “only at the moment when Lee handed Grant his sword” at Appomattox, and it was only thereafter that the “conception of Southern identity truly bloomed.”

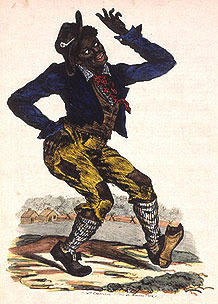

In its southern translation, as first popularized in Edward A. Pollard’s 1866 book The Lost Cause , the “Lost Cause” ethos not only defended succession and glorified the society that white southerners had gone to war to preserve, but actually transformed their tragic military defeat in a tremendous moral triumph. As Emory M. Thomas explained, “The Lost Cause mythology held that the southern cause was not only undefiled by defeat but that the bloodbath of war actually sanctified the values and mores of the Old South.” Proponents of the Lost Cause quickly pieced together a remarkably seamless historical justification of the actions of southern whites before and during the war. Though foisted on the South by the British with the assistance of northern slavetraders, in the hands of southern planters, slavery had actually been a benign, civilizing institution. Furthermore, the South’s antebellum planter aristocrats had supported succession not to preserve slavery but to secure nothing more than the individual and state rights granted by the Constitution. (62)

One of the most enduring myths to emerge from the era of Abraham Lincoln is the notion that the South fought the Civil War not to defend slavery, but to uphold the rights of states against a tyrannical central government. This myth was extremely important to the white South’s resistance to post-war Reconstruction, particular the effort by northern Republicans to secure basic civil rights and liberties for newly freed slaves. This states’ rights doctrine took concrete form during Reconstruction in the enactment of black codes by Southern states that sharply limited the freedom of African Americans.

Source: http://www.britannica.com/blogs/2011/...

In Black Boy Wright had forced white readers “to consider the South from the black point of view.“ Not surprisingly, many of them rejected what they saw. Mississippi’s race-baiting congressmen Theodore G. Bilbo and John Rankin denounced Black Boy as “a damnable lie from beginning to end” and the “dirtiest, filthiest, lousiest, most obscene piece of writing that I have ever seen in print,” pointing out that “it comes from a Negro and you cannot expect any better from a person of this type.” Some white liberals and a great many black leaders were also displeased with Wright’s unflinching portrayal of the intellectual and emotional barrenness of black life in the South and his suggestion that there was little reason to think things were getting better.

The irreverent novelist and folklorist Zora Neale Hurston had drawn consistent criticism from other black intellectuals for refusing to use her writings as a weapon in the struggle against racism and Jim Crow. Yet, in the original manuscript for her autobiographical Dust Tracks on a Road, she pointed out that “President Roosevelt could extend his four freedoms to some people right here in America. . . . I am not bitter, but I see what I see. . . . I will fight for my country, but I will not lie for her.” Like several others, this passage was subsequently excised after Hurston’s white editor deemed it “irrelevant.” Elsewhere, Hurston notes Roosevelt’s reference to the United States as “the arsenal of democracy” and wondered if she had heard him correctly. Perhaps he meant “arse-in-all” of democracy, she thought, since the United States was supporting the French in their effort to resubjugate the Indo-Chinese, suggesting that the “ass-and-all of democracy has shouldered the load of subjugating the dark world completely.” Hurston also announced that she was “crazy for this democracy” and would “pitch headlong into the thing” if it were not for the numerous Jim Crow laws that confronted her at every turn.

From its investigation of the Southern class system to its pioneering assessments of the region's legacies of racism, religiosity, and romanticism, W. J. Cash's The Mind of the South defined the way in which millions of readers -- on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line -- would see the South for decades to come.

A wide-ranging blend of autobiography and history, The South and the Southerner is one prominent newspaperman's statement on his region, its heritage, its future, and his own place within it. Ralph McGill (1898-1969), the longtime editor and later publisher of the Atlanta Constitution, was one of a handful of progressive voices heard in southern journalism during the civil rights era. From the podium of his front-page columns, he delivered stinging criticisms of ingrained southern bigotry and the forces marshaled against change; yet he retained throughout his career--and his writing--a deep affection for all southerners, even those who declared themselves his enemies.

Where Spencer, Welty, and Percy had simply moved from tacit acceptance to public criticism of segregation, in 1930 at age twenty-four, Robert Penn Warren had actually gone on record in its defense.