What do you think?

Rate this book

450 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 1984

“I spent a considerable amount of time when I was, o, adolescent, wondering why I was different, whether there were other people like me. Why, when everyone else was fascinated by their developing sexual nature, I couldn't give a damn. I've never been attracted to men. Or women. Or anything else. It's difficult to explain, and nobody has ever believed it when I have tried to explain, but while I have an apparently normal female body, I don't have any sexual urge or appetite. I think I am a neuter.”

Betelgeuse, Achenar. Orion. Aquila. Centre the Cross and you have a steady compass.

But there's no compass for my disoriented soul, only ever-beckoning ghostlights.

In the one sure direction, to the one sure end.

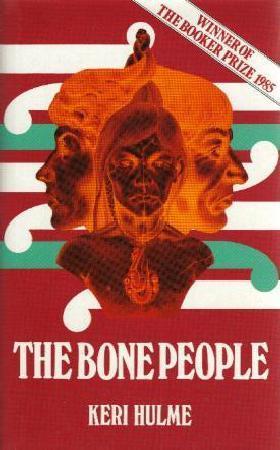

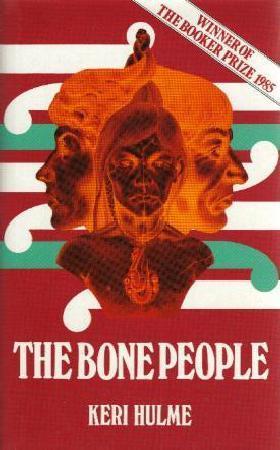

"In a tower on the New Zealand sea lives Kerewin Homes, part Maori, part European, an artist estranged from her art, woman in exile from her family. One night her solitude is disrupted by a visitor – a speechless, mercurial boy named Simon, who tries to steal from her and then repays her with his most precious possession. As Kerewin succumbs to Simon’s feral charms, she also falls under the spell of his Maori foster father Joe, who rescued the boy from a shipwreck and now treats him with an unsettling mixture of tenderness and brutality."Instead I discovered a book mixing poetry inside of prose, stream of consciousness inside of third-person narrative, rotating points of view inside three unusual minds, and a setting with fantastical elements, sometimes from Maori mythology, sometimes Keriwen's or Simon's own ideas. It was simultaneously easy and complex to read and is unlike anything else I can think of that I've read.