What do you think?

Rate this book

359 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1994

“None that speak of me know me and when they do speak, they slander me; those who know me keep silent and in their silence do not defend me; thus, all speak ill of me until they meet me, but when they meet me they find rest, and they bring me salvation, for I never rest.”

…running across the road and keeping as far from the kerb as possible, seeking shelter under eaves and in shop doorways and in the entrance to the metro, as had their forebears, wearing hats and longer skirts, when they ran to find shelter from the bombing during the long siege, clutching their hats and with skirts flying, according to photos and documentaries I’ve seen about the Civil War: some of those who ran to avoid being killed are still alive, whilst others born later are dead…

’[E]verything is continually travelling on, everything is connected, some things drag other things along with them, all oblivious to each other, everything is travelling slowly towards its own dissolution the moment it occurs and even while it is occurring…’

‘What a strange contact that intimate contact is, what strong, non-existent links it instantly forges, even though, afterwards, they fade and unravel and are forgotten…but not immediately after establishing those links for the first time, then they feel as if they were burned into you, when everything is fresh and your eyes still wear the face of the other person’The physical contact bonds us to others, and not only to those we immediately make contact with, but all those with whom we are now linked to by the process of our minds acknowledging that the other has contact with people beyond us and now we are linked to them through this chain of interaction. The narrator often tries to recall an old Anglo-Saxon term that failed to be adopted into the languages that stemmed from it, a term describing the bond between those who have shared a bed with the same person. The narrator feels an unbearable burden to acknowledge all the men he may ‘be related to Anglo-Saxon-style’, and posits that the word has not survived because ‘it isn’t easy to accept the act that it describes and it’s therefor better not to name it’, a ‘connection based on rivalry and unease and jealousy and drops of blood’. It is language that ties us together the most; language binds us with those around us and with those throughout all of human history.

‘everything depends on the end result doesn’t it, and that includes everything, even if it’s only an instant in time, one particular action varies depending on the effect it has.’This presents a reality in which truth and morality is subjective to an individual, and the reader must be ever conscious to see through the narrative as it is delivered by a mind utterly convinced of the validity of each action. What may come across as endearing could be viewed as creepy from an outside perspective, which is something we must all take to heart, remembering to think outside ourselves in our everyday interactions. If we do act in acknowledgement of the injustice of our actions, our soul buckles under the weight, and visions of ghosts may haunt us in our sleep. We become enshrouded in shadows, burdened by our desire to become whole again through the act of storytelling.

’Our lives are often a continuous betrayal and denial of what came before, we twist and distort everything as time passes, and yet we are still aware, however much we deceive ourselves, that we are the keepers of secrets and mysteries, however trivial’

“he dado la espalda a mi antiguo yo, ya no soy lo que fui ni tampoco el que fui, no me conozco ni me reconozco. Y yo no lo busqué, yo no lo quise.”la siempre incompleta y adulterada información con la que contamos para decidir;

“Un sí y un no y un quizá y mientras tanto todo ha continuado o se ha ido, la desdicha de no saber y tener que obrar porque hay que darle un contenido al tiempo que apremia y sigue pasando sin esperarnos”las intrincadas complicaciones y repercusiones que puede acarrear cualquier paso que demos por inofensivo que parezca; la enorme cantidad de posibilidades vitales que se mueven a nuestro alrededor y a las que por ser conscientes en una ínfima parte no podemos responder en consecuencia; el rápido olvido de lo que fuimos, sentimos e imaginamos, la poca constancia que queda de nuestra vida; el autoengaño en el que caemos al contarnos nuestra historia, al convencernos de nuestra identidad; y la necesidad de contar y contarnos, de convencer o hacernos entender, del perdón y hasta de algo de compasión, de sacarlo de nosotros y poder seguir viviendo; el enorme peso que puede significar nuestro pasado ("Mañana en la batalla piensa en mí"). En definitiva, lo frágiles, azarosas e insignificantes que son nuestras vidas. ¿Qué tema puede ser más interesante y más relevante que este?

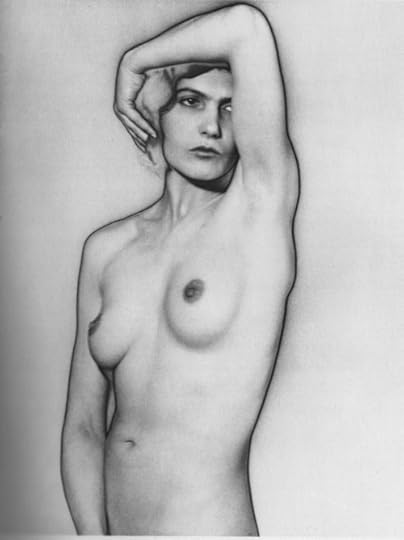

Everything is travelling towards its own dissolution and is lost and few things leave any trace, especially if they are never repeated, if they happen only once and never recur, the same happens with those things that install themselves too comfortably and recur day after day, again and again, they leave no trace either.The writing of Javier Marias is a different case altogether. Repetition and recurrence are common aspects of his books * and yet they always leave an everlasting trace on readers mind. He handles melancholy with a tender touch of his words and let the sadness tranquilly seep through our being but at the same time he keeps a strand of hope lurking around so that we can comfortably sail through the waves of dense narration he usually resorts to without losing sight of the horizon and gets the precious reward waiting for us on the other side of the shore. The vividness of his storytelling is a treasure to behold. I can still see that half-naked woman lying on her bed and slowly, without making any noise, without any apparent struggle, saying her goodbye to this world.

Tomorrow in the battle think on me, and fall thy edgeless sword. Tomorrow in the battle think on me, when I was mortal, and let fall thy pointless lance. Let me sit heavy on thy soul tomorrow, let me be lead within thy bosom and at a bloody battle end thy days. Tomorrow in the battle think on me, despair and die.Victor contemplates these lines from Shakespeare’s Richard III and relates it to his situation. A ridiculous situation. An unfortunate situation. A situation he didn’t choose for himself but now he can’t escape it. Then again, who choose to become a sole witness to a death? Who choose to make memories out of the last breath exhaled from someone’s red lips? Who choose to weave a story by pulling out threads out of the last moments someone spent in the arms of an almost stranger? Probably no one but life comes with its own bundle of surprises and dilemmas. Marías takes up these elements of life and indulge into a philosophical enquiry that treads a long path through unending sentences, frequent digressions and an eloquent prose. He leaves a reader numb by creating something magnificent with a tiny shred of a long forgotten past and illuminates the significance of a supposed inconsequential present. He makes us see and makes us admit that sometimes behind a normal facade, there hides both an angelic and a demonic form of our soul we never deem to exist. We never think ourselves capable of inflicting ruthless pain on someone or view ourselves as some sort of savior and before we know it, we becomes an inexplicable reason for somebody’s life and death.

It isn't just the minuscule history of objects that will disappear in that single moment, it’s also everything I know and have learned, all my memories and everything I've ever seen– my memories which, like so many of my belongings, are only of use to me and become useless if I die, what disappears is not only who I am but who I have been, not only me, poor Marta, but my whole memory, a ragged, discontinuous, never-completed, ever-changing scrap of fabric.