"My manner of thinking, so you say, cannot be approved. Do you suppose I care? A poor fool indeed is he who adopts a manner of thinking for others!"—Marquis de Sade

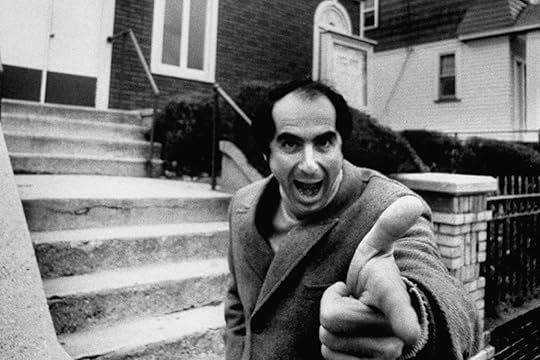

Reading Roth’s 1995 National Book Award-winning novel is not easy. At a little more than a year anniversary from his 2018 death, I took a look at all my higher-rated Roth books, now concluding with his last great book, his personal favorite of all his books, but not the personal favorite of all his readers. And now I re-evaluate the book, which I think I judged a bit too harshly in my initial review. I see the book in three parts, the first part of Mickey Sabbath's affair with his mistress Drenka; the second part is about his descent into madness primarily through his reliving the past, and the third part takes place at the Jersey Shore, where he meets 100-year-old Fish, an old neighbor, and where he recovers (comes to a greater appreciation of) memories of his brother Morty and his lover Drenka.

For much of the first part, almost a quarter of it, former puppet master and adjunct puppet theater instructor Mickey Sabbath (or, Morris Shabas) is having an affair with Drenka Balich. Most of what we read is about their intense sexual relationship, which is very graphic. But then you have to see that Mickey is a type, a satyr. He's not a nice guy (see above, and he makes this clear repeatedly by his actions and words throughout). You're not supposed to "like" him, he's maybe a bit like Humbert Humbert, an amazingly-crafted character that constantly challenges your impulse to try and find a way to admire or even sympathize with him (though he really does finally achieve a bit of this in the last part for me). Seen in this way he is a thoroughly interesting character, Roth pulling out all the stops with his richest language yet. You can how Roth delights in the old goat:

"He'd paid the full price for art, only he hadn't made any."

He was "just someone who had grown ugly, old, and embittered, one of billions."

"Despite all my many troubles," Sabbath tells Norman, "I continue to know what matters in life: profound hatred."

He's a misanthrope, through and through.

And while Drenka is as sex-obsessed as Mickey, it's not lovely romantic sex, it's unapologetically animalistic. And then (spoiler alert, sorry!) Drenka dies, which begins for Mickey a spiraling descent into comically suicidal (I know it seems strange to say this, but Roth pulls it off somehow) reflection—sometimes in Joycean stream-of-consciousness. That's another reference here, to Joyce, Drenka as Mickey's Molly. I guess you might call this strange book dark comedy or comic farce, recalling others who write unapologetically about sex (and death), from de Sade, to Rabelais to Henry Miller.

“Many farcical, illogical, incomprehensible transactions are subsumed by the mania of lust”--Mickey

Nothing is too outrageous for this guy, and I think Roth, who shocked and offended and delighted the literary world with Portnoy's Comlaint, goes way darker and so some people hate this far more. But he's deliberately shocking, deliberately unsentimental. He's not trying to "please" you with a redemptive story. You think you might begin to like him? Well, Roth says, watch Sabbath do THIS; do you like him now? And you squirm. I surely squirmed, and couldn’t read a lot of it at one time. But he isn't a character from Ametican Pastoral, he's not an admirable father or complicated ethical deliberator, he's just a great outrageous character.

“He’d never lost the simple pleasure, which went way back, of making people uncomfortable, especially comfortable people.”

“All I know how to do is antagonize.”

Thrown out of his house finally by his drunken wife Roseanna, disgraced by audiotaped phone calls confirming a relationship (at 60) with his 20 year old student, Kathy, Sabbath is a train wreck of a man, unemployed, and angry at the world, but knows he has no one to blame but himself.

“Mistressless, wifeless, vocationless, homeless, penniless,” he goes to Manhattan for a funeral, stays at the home of his former best friend, and steals the panties of his nineteen year old daughter “ . . . on the self-destroying hilarity of the last roller coaster.” We learn of the libidinous Sabbath’s life in street and off-off-Broadway puppeteering--The Indecent Theater of Manhattan--and of his many sexual escapades. We are not—I think now—asked to admire this devil, this man seen in the process of destroying his life, but in these early years we can almost see his comically bawdy show and smile at his outrageousness; that is, until he gropes a woman from the audience engaged with him in one of his street theater shows, and charges are pressed against him by a passing cop (not by the woman; she sees it all as part of his act). Just when you begin to maybe begin to like him, he slaps you in the face.

“I am disorderly conduct.”

In Manhattan he meets his first wife, Nikki, who (spoiler alert) mysteriously disappears, leading him to escape to upstate New York and to the arms of another wife, Roseanna, who barely is able to stay with him until his public disgrace over the affair with his student makes it finally impossible. We are not led to cheer on this old horny goat, who is at the time of the tale told 64. This guy is a failure, an often arrogant, usually articulate, sometimes funny, sometimes disgusting pig whom we see suddenly faces despair and possibly death. You decide:

“In the masterpieces people are always killing themselves when they commit adultery. He wanted to kill himself when he couldn’t.”

“. . . those ejaculations leading nowhere.”

“The walking panegyric for obscenity. The inverted saint whose message is desecration"—Norman, about Sabbath

And yet, Sabbath, purchasing his gravesite, is funny; just when you have given up on any shred of decency in the man, he is finally thoughtful, anguished, seeing things closely for maybe the first time. I begin to even care for him when he finds, in his 100-year-old ex-neighbor Fish’s house, a box with his dead brother Morty’s artifacts in it, something that turns him around (for a bit? For good?). Each successive act of disaster leads him back in memory to Morty, killed in WWII, and Nikki, his missing wife, and to his lover Drenka, whom we can finally accept as the love of his life.

Sabbath is in the end King Lear, at least as he sees himself; not maybe quite admirable, but maybe Lear and Fool together, wrapped in his brother's honorary American flag, wearing his red, white and blue yarmulke. This is an image you will not forget, I think. As Drenka says of him,

“You are America.”

Roth as fiction writer is not unlike Sabbath in his puppet theater, manipulating his audience, messing with us, crossing the line and groping us, though sometimes impressing us! Creating illusions. Here's one, or is this real?

“We are immoderate because grief is immoderate, all the hundreds and thousands of kinds of grief.”

And then Mickey says of himself, in case we think he is just a joke: “I do not say correct or savory. I do not say seemly or even natural. I say serious. Sensationally serious. Unspeakably serious. Solemnly, recklessly, blissfully serious.”

Roth (RIP 1933-2018) has said that Sabbath's Theater is his favorite book, the one he had the most fun writing. Fun!? Well, I can see that. Yes, the act of creating, the sheer language in it! It’s not my favorite Roth—American Pastoral is mine--but I can finally appreciate it for its powerful literary achievement, maybe his most impressive accomplishment.