Mark Mordue's Blog

May 7, 2017

งานกรอบรูปแนวโมเดินร์น

กรอบรูปนั้นมีหลากหลายแบบทั้งแบบแอนติดแบบโบราณ หรือแบบแนวต่างๆ ลายไทย ก็เหมาะกับบ้านแนวโบราณหรือแนวทรงไทยๆ หน่อยถึงเหมาะสม หรือไม่ว่าจะเป็น กรอบรูปแนวหลุยส์ก็เหมาะกับแนวงานแต่งงาน สวยๆ และเหมาะกับงานโรงแรม หรือบ้านหรูๆ และสวยๆ ก็ทำให้สถานที่ต่างๆก็ทำให้บ้านเราดูดีขึ้น แต่ทรงหรือแนวที่เหมาะมากในปัจจุบัน เช่นกรอบลอย กรอบรูปแคนวาส แบบลอย หรือไม่ว่าจะเป็นไม้แบบแนวๆโมเดิร์นสวยๆ ขาว หรือดำเรียบๆ ใช้ไม่เบื่อและทำให้บ้านเราดูทันสมัยอยู่ตลอดเวลา และทำให้คนที่อยู่ในบ้านรู้สึกสดชื่นได้ครับและเมื่อแขกไปใครมาก็ทำให้เราเจ้าของบ้านนั้นดูดีและน่าชื่นชมด้วยครับ ดังนั้นการเลือกกรอบรูป หรือแนวการตกแต่งบ้านสำคัญเช่นกันนะครับหากท่านใดกำลังตกแต่งบ้านอย่าลืมเลือกกรอบรูปหรือแนวให้เข้ากันกับบ้านของเราด้วยนะครับ

Published on May 07, 2017 06:38

January 15, 2017

กรอบรูปงานแต่งงาน ของประดับที่สำคัญ

กรอบรูปงานแต่งงานเป็นอีกอย่างที่ขาดไม่ได้ครับเพราะในงานแต่งงานนั้น พระเอกสำหรับในงานไม่ใช่แต่เพียงคู่บ่าวสาว หรือว่าเป็น แขกผู้ร่วมงานเท่านั้นและอีกสิ่งที่สำคัญไม่น้อยกว่าเลยคือ กรอบรูปที่ใช้่ประดับในงานแต่งงาน เพราะเป็น ของประดับที่สำคัญไม่น้อยกว่าอย่างอื่นเลยครับไม่ว่าจะเป็นของชำร่วยหรือว่าจะเป็น ฉาก ดอกไม้หรือ ซุ้มดอกไม้ แต่กรอบรูปถือว่าเป็นพระเอกในงานก็ว่าได้ครับ เพราะบ่งบอกถึงความเป็นตัวของทั้งคู่ด้วยครับเพราะเป็นเรื่องราวของความรักความผูกพันธ์ ของคู่บ่าวสาว

และเรื่องราว กรอบรูปแต่งงานนั้นมีหลากหลายแบบ ทั้งกรอบหลุยส์ที่นำไปวางไว้หน้างานแต่ง หรือกรอบลอย กรอบลอยผ้าแคนวาส ที่กำลังนิยมเป็นอย่างมากครับ แต่ละแบบก็สามารถประดับได้หลากหลายสไตล์ และมีเอกลักษณ์ในตัวเองครับดังนั้นหากใครคิดจะหากรอบรูปแบบต่างๆมาประกอบงานก็ควรดูให้เข้ากับรูปแบบและงานของท่านด้วยนะครับจะได้มีงานที่สมบูรณ์และทรงคุณค่าที่สุดในชีวิตแต่งงานครับ

และเรื่องราว กรอบรูปแต่งงานนั้นมีหลากหลายแบบ ทั้งกรอบหลุยส์ที่นำไปวางไว้หน้างานแต่ง หรือกรอบลอย กรอบลอยผ้าแคนวาส ที่กำลังนิยมเป็นอย่างมากครับ แต่ละแบบก็สามารถประดับได้หลากหลายสไตล์ และมีเอกลักษณ์ในตัวเองครับดังนั้นหากใครคิดจะหากรอบรูปแบบต่างๆมาประกอบงานก็ควรดูให้เข้ากับรูปแบบและงานของท่านด้วยนะครับจะได้มีงานที่สมบูรณ์และทรงคุณค่าที่สุดในชีวิตแต่งงานครับ

Published on January 15, 2017 07:04

กรอบลอยผ้าแคนวาส กรอบลอย เคลือบลามิเนต เป็นอย่างไร

กรอบลอยเป็นกรอบรูปที่หลากหลายท่านคงรู้จักกันดีไม่มากก็น้อยนะครับ ไม่ว่าจะเป็นวัยรุ่นๆ หรือว่าวัยทำงาน หรือท่านที่กำลังจะแต่งงาน ไปจนถึงวัยผู้ใหญ่ ก็คงเคยเห็นกรอบรูปลอยมากกันแล้วนะครับเพราะสมัยปัจจุบันนี้ เป็นที่นิยมมากๆครับไม่ว่าจะนำมาประดับตกแต่งบ้าน หรือว่านำมาเป็นกรอบรูปของขวัญให้เพื่อน ให้แฟน หรือให้วันเกิด วาเลนไทน์ ก็ถือว่านิยมมากๆครับเป็นของขวัญที่ไม่น่าเบื่อ ดูมีคุณค่าและยังเต็มไปด้วยเรื่องราวและความสวยในตัวครับ กรอบลอยนั้นคุณภาพดีต้องเคลือบลามเนต ครับเพื่อป้องกันหน้าภาพให้อยู่ทนทาานนานนับสิบๆปี และ สีก็จะสดใสอยู่ตลอดครับ ส่วนกรอบรูปลอยที่ทำจากผ้าแคนวาสนั้นก็เป็นอีกวัสดุที่นิยมมากๆเช่นกันครับเพราะเป็นการพิมพ์ผ้าแคนวาส ด้วยสีคุณภาพและนำมาทำโครงกรอบลอยสวยๆ ประดับบ้าน น้ำหนักเบาและยังเต็มไปด้วยความมีศิลปะอย่างยิ่งครับ หลากหลายท่านนำไปตกแต่งบ้าน หรือว่านำไปประดับแกลลอรี่งานแต่งสวยๆครับ ให้เพื่อน น้อง แฟน รุ่นพี่ก็เป็นที่ถูกใจทุกคนครับ หากใครคิดจะหาของขวัญ หรือของแต่งบ้าน กรอบลอย เป็นอีกอย่างครับที่ดูน่าสนใจและไม่แพงสำหรับทุกท่านเลยทีเดียวครับผม

Published on January 15, 2017 06:57

January 7, 2017

ของขวัญกรอบรูปอะไรให้เพื่อนแล้วเขาจะถูกใจ

กรอบรูปนั้นมีหลากหลายครับไม่ว่าจะเป็นกรอบรูปไม้แบบโบราณ หรือว่าจะเป็นกรอบรูปหลุยส์

สีต่างๆ นั้นต่างมีแบบและสไตล์ในตัวที่เราควรเลือกให้ถูกกาลเวลาและสถานะที่ควรค่าเช่นถ้าเราจะให้เพื่องานแต่งงาน เราควรให้กรอบรูปที่ไม่ดูเด่นเกินไปนัก และ น่ารักและดูมีสไตล์ เช่นกรอบรูปผ้าแคนวาส กรอบลอย หรือว่า กรอบรูปไม้กล่องสีขาวโมเดิร์น ทำให้ผู้รับนั้นชอบเพราะสามารถนำไปตกแต่งบ้านได้ง่ายและ ดูน่ารักตลอดใช้งานได้ทุกสไตล์ของบ้านทุกทรงทุกแบบครับ ส่วนถ้าเป็นของขวัญรับปริญญาตอนนี้ก็ นิยมแคนวาส มากๆครับเพราะกรอบรูปผ้าแคนวาส นั้นดูมีความคลาสสิคคล้ายภาพวาดในตัวครับทำให้ผู้รับนั้นประทับใจในงานของผู้ให้และยังทำให้ง่ายต่อการพกพาเพราะแคนวาสนั้นเบาและง่ายต่อการพกพาสะดวกมากครับ ดังนั้นหากจะทำกรอบรูปนั้นควรพิจารณาหลายๆประการเพื่อความเหมาะสมโอกาสและกาลเวลาด้วยนะครับผม

สีต่างๆ นั้นต่างมีแบบและสไตล์ในตัวที่เราควรเลือกให้ถูกกาลเวลาและสถานะที่ควรค่าเช่นถ้าเราจะให้เพื่องานแต่งงาน เราควรให้กรอบรูปที่ไม่ดูเด่นเกินไปนัก และ น่ารักและดูมีสไตล์ เช่นกรอบรูปผ้าแคนวาส กรอบลอย หรือว่า กรอบรูปไม้กล่องสีขาวโมเดิร์น ทำให้ผู้รับนั้นชอบเพราะสามารถนำไปตกแต่งบ้านได้ง่ายและ ดูน่ารักตลอดใช้งานได้ทุกสไตล์ของบ้านทุกทรงทุกแบบครับ ส่วนถ้าเป็นของขวัญรับปริญญาตอนนี้ก็ นิยมแคนวาส มากๆครับเพราะกรอบรูปผ้าแคนวาส นั้นดูมีความคลาสสิคคล้ายภาพวาดในตัวครับทำให้ผู้รับนั้นประทับใจในงานของผู้ให้และยังทำให้ง่ายต่อการพกพาเพราะแคนวาสนั้นเบาและง่ายต่อการพกพาสะดวกมากครับ ดังนั้นหากจะทำกรอบรูปนั้นควรพิจารณาหลายๆประการเพื่อความเหมาะสมโอกาสและกาลเวลาด้วยนะครับผม

Published on January 07, 2017 22:24

November 24, 2013

High Tide: Ian McEwan's On Chesil Beach

"They were young, educated, and both virgins on this, their wedding night, and they lived in a time when a conversation about sexual difficulties was plainly impossible. But it is never easy."So Ian McEwan begins his latest novel, a short but highly charged work of fewer than 180 pages. The year is 1962 and the newlyweds are Edward and Florence, names that reek of an old world the '60s would soon transform.When the book opens they are being served dinner in their hotel room on the Dorset coast of England by two trussed-up local lads who seem as awkward with the occasion as they are. In the distance the waves of Chesil Beach can be heard breaking, a sound of "gentle thunder, then sudden hissing against the pebbles".Initially, McEwan's writing is restrained and formal, a quint- essentially British tone befitting the time in which it is set. One thinks of old BBC radio plays and "hears" the story being told. It would be easy to mistake this as tame fare indeed but for a sly humour and confidence percolating beneath McEwan's voice:"This was not a good moment in the history of English cuisine, but no one much minded at the time except visitors from abroad. The formal meal began, as so many did then, with a slice of melon decorated by a glazed cherry ... It would not have crossed Edward's mind to have ordered a red."McEwan's intent, however, is not drawing room comedy. Ominous descriptive traces like the "hissing against the pebbles" and far rawer feelings are pulsing within a few pages. The internal mechanics of the book quickly reveal themselves as we discover who Edward and Florence are (he an aspiring historian, she a young violinist), diving into their thought patterns and family memories, reliving the romance between them and returning to the events of the wedding night as seen through the eyes of each.Virtually everything that happens in On Chesil Beach occurs during this one evening and the tidal intensity, the back and forth between Edward and Florence, is palpable as it leads us down, finally, to the beach itself and the book's climactic scene.McEwan exposes the rationalisations and self-deceptions we all succumb to in situations of great emotional uncertainty, the shifts in perception that show what changeable and unpredictable beings we can be to ourselves, let alone one another. In doing so, the book takes us deeper into two people's lives, counter-pointing the tensions of the present with the great backwash of their past and the surging of a future neither can fully see.

As the extent of Florence's fear of sex becomes clear - "her whole being was in revolt against the prospect of entanglement and flesh ... sex with Edward could not be the summation of her joy, but the price she must pay for it" - we are clued into Edward's long-standing awareness of her repressive personality. Florence's genuinely loving affection, along with her passion for playing the violin, has allowed him to deceive himself of what must be "her richly sexual nature" and what he mistakes for simple shyness. Florence, of course, is at pains to make it seem this way. Edward, not entirely insensitive to these tensions and resistances, tries to be understanding, to take their wedding night slowly. By the time she is moaning in disgust at his touch he is interpreting it as the sound of ecstasy.It's hard to say more without giving away the plot of this slender book. Suffice to say the emotions and ideas are profound in what might seem like the narrowest of circumstances. And though the focus remains overwhelmingly intimate - newlyweds in a hotel bedroom, mutual concerns about when they will have sex and how it will go - McEwan summons up the Cold War atmosphere with textures like the wireless playing downstairs, from where Edward hears the word "Berlin" and to where Florence wishes she could flee, "to pass the time in quiet conversation with the matrons on their floral-patterned sofas while their men leaned seriously into the news, into the gale of history".

McEwan has always been a political writer, as demonstrated in works as varied as his film script for The Ploughman's Lunch (1983), a critique of life in Thatcher's Britain, or his last brilliant novel, Saturday (2005), an attempt to grapple with the nature of violence and human connectedness in a post-September 11, 2001, world. His reflections in The Guardian on the events of September 11 still stand out among the best things written at the time. Whether penning an elegy for a deceased author like Saul Bellow or speaking with deep ambivalence about the Iraq War, he remains committed to the engaged notion of a public intellectual.And yet there's a provocative, almost mathematical coolness to his writing that undercuts the comforting status of a literary good guy.His debut collection of short stories, First Love, Last Rites (1975), opened with the tale of a boy telling you, in a bemused tone, how he raped his sister. McEwan's ability to evoke the psychotic pull of a murderer in The Comfort of Strangers(1981) or a stalker's obsession in Enduring Love (1997) similarly displayed his taste for evil and violence in ways that appeared irresistible, almost mystical.This interest in the sexually aberrant, the bizarre and the psychologically unsettling led to McEwan being nicknamed Ian Macabre early in his career. Over time McEwan's books have become less overtly strange (one of his most acclaimed short stories, Solid Geometry, deals with a man who discovers how to fold his wife up like a piece of paper and make her disappear) and more everyday in their intensities. And yet the same neo-gothic traits of lives lived in secret and looming darkness infect all his works with threat and fear.When McEwan won the Booker Prize in 1998 for Amsterdam it was largely seen as a lightweight work in his career, a tightly plotted entertainment. On Chesil Beach is similarly short, but far more serious, harking back to the compressed nature of his early and most haunting short stories, as well as McEwan's long-running interest in the random and banal ways ordinary lives can be shattered.It is proof that no life is completely private or shut off from the world, that we can be victims of ourselves and, if we're unlucky, our historical moment, too.

- Mark Mordue

* First published in Sydney Morning Herald Spectrum Books, April 6 2007

+ Photo of Ian McEwan taken at Paris Book Fair, 2011. Accessed via Wikipedia Commons. Image made by The Supermat - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sal...

Published on November 24, 2013 17:46

October 27, 2013

Paul Kelly: One Day at a Time

Paul Kelly's back in town. I meet him at a King's Cross hotel where his daughter, Madeleine, is turning her slice of cheese into a jigsaw puzzle that makes sense only to her.On his new album, Deeper Water, Kelly has named a song after her. The chorus? "Madeleine - you never let me sleep." Fathers everywhere will empathise.While the four-year-old tugs persistently at his hand, Kelly's two-year-old daughter, Memphis, is in another room recovering from carpet burns to the face after she dived off a hotel lounge headfirst onto the floor.Actor Kaarin Fairfax is, meanwhile, seeing an old friend, the portrait photographer Wendy McDougall, out the door. Kelly met Fairfax in 1988 when she starred in Sam Shepard's Lie Of The Mind. "We were just hanging at the bar," Kelly recalls, throwing the memory to Fairfax like an old joke.The pair married in 1993. With two young children and stretches of time in Los Angeles - where Kelly has been based kick-starting an American career - Kaarin Fairfax hasn't had much time for acting. That's changing now the family is back in Australia."I did Correlli," Fairfax says, acting tough, pushing words out the side of her mouth, "playing a criminal's goil-friend."At the centre of all this, Paul Kelly just hangs back quietly. Despite the hyperactivity, it's clear his family life protects him - that Kelly pulls it around him like a warm blanket. Seeing him on the couch with Madeleine when I arrive, he's oddly calm, oddly vulnerable.As he will say later, when discussing his returns to Australia after overseas jaunts: "I like to come home. It's OK here."Kelly's manager, Rob Barnham, starts ticking off the day's media itinerary with Kelly. I'm tagging along for the afternoon to get a closer look at one of Australia's favourite songmen.Late last year Kelly toured Europe and America and he's playing at home this month. In typical Kelly fashion, the songs from Deeper Water have become part of our lives."That's why you write songs," Kelly says, as if it's nothing special and certainly obvious. "You want them to be in people's lives."With the Helen Demidenko/Darville controversy still percolating, Kelly's eager to say The Hand That Signed The Paper “is good writing. But all the Jews in the book are communists. So it's bad history." It's a crucial distinction for Kelly, whose poet of the common man credentials are built on both good writing and accuracy - whether it be something as subtly textured and local as allusions to "a Silvertop" taxi (‘To Her Door’) or Randwick bells (‘Randwick Bells’), or a turning point in the history of the land rights movement (‘From Little Things Big Things Grow’)."I've always liked concrete writing with pictures and details," says Kelly with relish. "Chuck Berry was a great example of that. I'm very conscious of it. I wanted to map where I came from the way Chuck Berry mapped out America."

Dressed in a brown bomber jacket with a blue T-shirt and jeans, Kelly's hair is close and short. I'm sure he has dressed this way for ages, rock 'n' roll basic, nothing too flash. As he says of writing: "Simple is always best."But the 40-year-old seems slimmer than a year ago, somehow sharper than the sated, middle-aged bloke who last toured. Wanted Man, from 1994, was a critical low point for Kelly. Despite some great live shows, the album sounded like a songwriter falling off the face of American FM rock with a dull thud. Was the guy losing his touch, or getting soft because of family life and success?Ask Kelly about Wanted Man's artistic failure, ask him about Deeper Water and its profound return to form - his best form ever - ask him if he sees Deeper Water as more coherent, more feeling on every front, and he just shrugs his shoulders."My friends like this record better," he finally admits, under pressure. "It's more of a band record I think." Then he laughs. "All my records feel like they're scraped together. Deeper Wateris just what I did this year."Rather than shy or aloof, Kelly's just a quiet guy. Stillness is one of his most potent qualities. It makes him easy company. Strong company, too.Back when he was the socket-eyed, leather jacketed poet of the early '80s Melbourne music scene with his band The Dots, that stillness simmered with self-destructiveness.Listen to Post, his stark account of heroin use, inner-city relationships and people dying, hear ‘From St Kilda To Kings Cross’, and you'll get something of the world he left behind when he came to Sydney to live for a few years.Kelly prefaced his book of lyrics, (called Lyrics) with a quote from Chekov: "I don't have what you would call a philosophy or coherent world view, so I shall limit myself to describing how my heroes love, marry, give birth, die and speak."On Deeper Water parenthood is Kelly's dominating theme. But Kelly's propensity for mawkishness is absent, and his spare eye never lets the colloquial slide into cliché. Deeper Water's take on family, growing older and love also has a dark edge to it, something in the territory around the songs, that gives the album an unusual intensity and warmth.Kelly weighs up what I'm trying to say with that observation, weighs it quite considerably."I have a pretty good life now," he finally sighs. "But it ... feels like it's endangered. Or precious, or fragile - maybe that's what I'm trying to say. Maybe it's to do with having children or something but, as a parent, you have to be prepared for disaster."He starts to talk about his song ‘Gathering Storm’. "It sounds like someone waiting for a lover. What was at the back of my mind when I wrote it was a parent worrying about a child. And how there's so much ... a lot of danger."If Kelly deals with parenthood and the powerfully related theme of mortality in songs like ‘Deeper Water’ and ‘Gathering Storm’, he also deals with sex with unusual rawness and heart. His song ‘Blush’ exalts to the summer beach lyric: "When we kiss she tastes so salty/On her cheek and her neck/I can't wait till I get with her/So I can kiss her salty breasts.""It's really hard to write about good sex or write straightforwardly about sex without being banal about it," he says. Citing Motown music, Kelly adds "the great thing about a lot of soul music is that they wrote about sex and joy really well. Whereas the singer-songwriter tradition is about things that went wrong, the complications and the unrequited."He shakes his head. "When I was last in America I was listening to modern r'n'b, urban radio. They played rap, hip-hop and they'll have balladry, but horrible songs all about sex and "doing it', and always the singers doing vocal gymnastics that are very explicit and ... well, just horrible."At Soundcom, an organisation responsible for Ansett's in-flight music as well as in-store sounds for the likes of Just Jeans and Woolworths, Kelly's asked to play a couple of songs, and it turns into a free concert for the staff, who file in smiling, waiting nervously for him to begin. The intimacy in the small conference room between Kelly's performance and this audience of 20 is absurdly reverent and close.He chooses ‘Blush’, then ‘Queen Stone’, a thinly disguised paean to heroin, the dark muse, written by his old guitarist Maurice Frawley. Then he follows with ‘Difficult Woman’, which he wrote for Renee Geyer - "I got my hands full with a difficult woman."Overall it's a sweet, gently intense effort. Everybody claps, absolutely beams appreciation. The love is palpable. Kelly puts his guitar down, embarrassed. "If I'd known you were all coming I'd have practised more."Outside, in the daylight, Kelly says the experience was "a bit strange". He seems quite rattled, then he laughs. "During the last song I suddenly got a flash of one of those Elvis Presley movies." I tell him about a saying I heard at a party a few months ago. "Scratch an Adelaide person, find an Elvis." Kelly snorts, keeps laughing to himself, then finally says between fits of chuckling: "I'm from Adelaide, you know."

- Mark Mordue

* Story first published as ‘Poet of the Common Man’ in the Sydney Morning Herald Metro, January 12, 1996.

Published on October 27, 2013 20:28

September 2, 2013

Learn to Fly

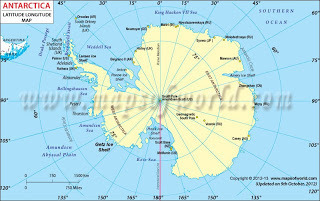

Burn the birdsBurn them nowUse our fire, breath fear on their wings.We gulp down lies and simplificationsLike petrolSpit it out. Circus jerks.“Here we are now, entertain us.”My vote for you protects my perks:Islamic racists loving mini-skirts.Burn the birdsLet’s wipe the sky with tongues of flameKeep them out. The old, the young, the lame.We love a sun-fun countryA lad of chefs and sushi trains.To many fuckers, too many fish with feathers.Call the monk. Club and crucifix.Burn the birds. They have no name.Perks. Jerks. Soon we’ll all be runningBad weather is coming.Hide the money from our children.Down in Antarctica among the last stonesSomeone called The Leader can explainWhy it was we ate tomorrow.Bird bones in our throats. No brains.

- Mark Mordue

Published on September 02, 2013 02:44

July 30, 2013

"What will survive of us is love": Isabel Fonseca's Attachment

It's 10am in Primrose Hill, London. The author Isabel Fonseca sits in her kitchen, "tanking up on coffee". An American by birth and a New Yorker at heart, she says, "I can't believe I've lived in England for over 25 years or whatever it is. It's payment for my sins. Or maybe I just forgot to leave."Her tone has a throwaway flash to it; just joking, right? Fonseca corrects me immediately. "I'm not, you know."Why such resentment towards her adopted home? After all, England made her, so to speak. From a philosophy, politics and economics degree at Oxford to her role as an assistant editor at The Times Literary Supplement and the publication of Bury Me Standing in 1995, a non-fiction study of the gypsies of Eastern Europe.That book involved five years of participatory journalism, living and breathing her subjects' lives from Albania to Estonia. Upon publication Salman Rushdie called it "a revelation: a hidden world"; Edward W. Said praised its "profound sympathy and brilliant insight".In the meantime, Fonseca was making other news over her affair with Martin Amis. She had already picked up the nickname "Funseeker" on the London social circuit, as well as a slew of admirers that purportedly included John Malkovich, Clive James, Bill Buford and, yes, Salman Rushdie.Men fairly wilted before Fonseca and to this day, at age 46, there is not an article on the internet from The Sunday Timesto W Magazine that does not still remark upon her beauty. A formidably intelligent brunette, her dark looks reflected the heritage of her Uruguayan father, a highly regarded sculptor, and her Jewish American mother, a painter and heiress to the Welch grape juice family-company fortune.Amis would eventually leave his first wife, Antonia Phillips, and their two sons; get a hotshot American agent, a seriously big American publishing deal and even get his teeth fixed. Fonseca was the scarlet woman behind this scandalous Americanisation of a British icon, a cliche that ignored Amis's long-running transatlantic obsessions, not to mention the fact Phillips was an American academic. Fonseca and Amis would go on to marry in 1998 and now have two daughters, Fernanda, 11, and Clio, 9.When I ask Fonseca about her antipathy to England, she's quick to refine it into something more good-natured: "Oh it's all right. London's just too expensive to be loveable … Actually we just spent a few years living in South America. And it was wonderful, charming, heaven. But I don't mind being in the wrong place. I think for a writer being in the wrong place is often a very good thing."Back in 2004 Fonseca and family decamped to Uruguay for 2½years in the wake of her father's death. There Fonseca attempted to write and then abandoned a major non-fiction work on her extended family. During that time she turned to "what was, I thought, a short story at first" before it evolved into the highly intimate book she now calls Attachment.Attachment is not only Fonseca's debut novel it is her first major work since Bury Me Standing. In it she quotes these crucial, if ambiguous words from Philip Larkin's An Arundel Tomb: "What will survive of us is love."Like the Larkin poem, Attachment takes a somewhat anti-romantic view of romance, before leaving us with a bittersweet and defiantly fragile ending. The book's central character is Jean Hubbard, a syndicated American health columnist married to a high-achieving British advertising executive called Mark. Mark is described as "six feet four in bare feet and striking with his grayed hair swept back, wind-eroded dune grass above the expanding beach of his face". This alone sounds like an awfully good depiction of Amis with a height boost, not to mention a more commercialised slant on his and Fonseca's literary preoccupations.Like Fonseca, Hubbard has a background that includes having once worked as a paralegal for the summer in New York; she similarly buys pot as a teenager in Washington Square; studies at Oxford; is shadowed by a brother who has died tragically young; deals with a father who is critically ill; and copes with the unexpected appearance of a young woman who might be her husband's daughter (Amis discovered he had an unknown daughter called Delilah Seale in 1997). That the opening of Attachment is set on the imaginary island of St Jacques - supposedly located somewhere near Mauritius, but also a hot, exotic place not unlike Uruguay - brings it even closer to home.When Attachment begins, Hubbard discovers a sexually provocative letter that leads her to a secret email link and an affair her husband has been having. To find out more about it Hubbard begins writing to "Giovanna" as if she were her husband. This incites Hubbard to abandon herself to a night of infidelity back in London, and to later flirt with an old lover in New York while her father hovers on the critical list in hospital. "Everything was sullied and she was rotting from within," Hubbard reflects as she delves into a world of internet affairs and online pornography. Later, as she embraces a path of disillusionment to license her own betrayals, she admits "this was the consequence she most feared: her own revulsion for her world, for all that she had. Auto-eviction."Britain is already abuzz with Attachment as an adulterous and confessional insight into a less-than-happy marriage - as well as the critical complications of dealing with a work that may or may not be a roman-a-clef. Attachment is a novel of great promise but it ebbs and flows in its intensity according to the proximity one feels between the author and her "truths". In short, the things Fonseca seems to have experienced are powerfully evoked; the things she appears to have imagined feel forced or contrived.Fonseca runs a nice line in self-deprecating humour and frankness. But in the course of an hour's conversation she puts herself to the test of her own thinking repeatedly and seems to find herself wanting. Talking on the phone there's that strange, floating sense you have not so much entered her home as her headspace: an inner world so thoughtful and honest it can leave you feeling cowardly by comparison."There's a long period of merger in the beginning of any relationship," Fonseca says. "Then with children you sense you have to keep a united front. My daughters are nine and 11 now. Old enough to get your space back a little. You see that you still have a long way to go - I hope! That I'm only halfway … But you also ask, 'Is that it?' Not as a matter of complaint, more as a matter of stupefaction." Fonseca almost laughs. "Here I am, I've made babies, but who am I now that I am on my own again?"She's adamant "adultery is not the subject of Attachment, but ageing is. There's this disappointment about your decrepitude, this realisation you are going to die which you have never quite accepted. Adolescence and middle-age actually share a lot of parallels. The unease about the body and the sexual awareness that's associated with it, only you have this death awareness that gives it a particular pungency in middle age. Things like the way your parents suddenly demand your attention with their mental or physical fragility or both; or something as simple as the way your children won't do what they're told any more."Coincidentally Bury Me Standing and Attachmentboth resound with a quest for home. "Whenever you write it is to investigate some anxiety. Writing about the gypsies there was some public anxiety with identity. Fiction is more about scratching about in a silent anxiety. And your sense of identity often relates to what home means, I guess. I didn't set out to do that. But I see now there's a lot of homesickness in the story [of Attachment] … Maybe it's a cliche of fiction that the past is another country. But this nostalgia for the time before is so often identified with place as much as time.""You know I still go to New York about four times a year for various reasons. One of the real, but less legitimate reasons I do it is you can imagine life before it happened to you, when things could have gone 19 different ways. I think that's why I'm lucky to be a writer. Because you can think about and write about such things, just to see how you feel."

- - Mark Mordue

· * First published as ‘Well written in the Wrong Place’, Sydney Morning Herald Spectrum, June 14, 2008

Published on July 30, 2013 21:56

July 18, 2013

The Lost Worlds: Anna Funder's Stasiland

"I am hungover and steer myself like a car through the crowds at Alexanderplatz station. Several times I miscalculate my width, scraping into a bin, and an advertising billboard. Tomorrow bruises will develop on my skin, like a picture from a negative."

And so we begin. Caught inside a "headspace." Having trouble with our borders, as if the damaged compass of our narrator will map its own unpleasant realities across us the further as we move into her story. Bruises of another kind.In the company of the Australian writer Anna Funder words have a cool poeticism and metaphoric sharpness that prick deep, reflective emotions inside the reader. It is the language of ice, winter, enclosure, and, of course, death.So it is that you don't just browse through the Stasiland's pages on some idiosyncratic tour of present-day, techno-grooving Berlin (as the sexy cover art for the Australian edition might suggest); instead you pass through a netherworld of bad historical memories and the damaged lives that still inhabit it.With a fearlessness that seems guileless for someone so perceptive, as if Funder has never been truly hurt or endangered before, the author dives into the history of the laughably named "German Democratic Republic" and its former security force, "the Stasi", whose surveillance culture dominated East Germany during Communist rule and continues to haunt many of its populace today. She does this simply by posting an advertisement in the local paper "seeking former Stasi officers and unofficial collaborators for interview." It is the opening act on the proverbial can of worms."People here talk of the Mauer im Kopf or the Wall in the Head," Funder writes. "I thought this was just a shorthand way of referring to how Germans define themselves still as easterners and westerners. But I see now a more literal meaning: the Wall and what it stood for do still exist. The Wall persists in Stasi men's minds as something they hope one day might come again, and in their victims' minds too, as a terrifying possibility."Stasi headquarters was known as "the House of One Thousand Eyes." Funder explains, "At the end, the Stasi had 97,000 employees--more than enough to oversee a country of seventeen million people. But it also had 173,000 informers among the population. In Hitler's Third Reich it is estimated that there was one Gestapo agent for every 2000 citizens, and in Stalin's USSR there was one KGB agent for every 5830 people. In the GDR there was one Stasi officer or informant for every sixty-three people. If part-time informers are included, some estimates have put the ratio as high as one informer for every 6.5 citizens."In this kind of world, secrecy and surveillance were not without their bureaucratic absurdity. At one point Funder cites a Stasi file note from 1989, the year the Wall finally fell, in which "a young lieutenant alerted his superiors to the fact there were so many informers in church opposition groups at demonstrations they were making these groups appear stronger than they really were. In one of the most beautiful ironies I have ever seen, he dutifully noted that it appeared that, by having swelled the ranks of the opposition, the Stasi was giving the people heart to keep demonstrating against them."The preying density, the absolute complicity of it all, leads Funder through a world of broken and repressed lives that no shorthand summary can do justice to: a mother separated from a critically ill son by the building of the Wall in 1961; a budding young linguist denied a career, then a love life, and finally the ability to love, by the encroaching thuggery of the State; a maverick rock star refused his public existence by the annulling force of the security apparatus. You meet them all in Funder's strangely permeable company; feel something of their lost quality as one might feel the hurt of familiars. At one point Funder admits, "No one can ever tote up life's events and calculate the damages; a table of maims for the soul." But in Stasiland she most certainly tries.Beyond the victims she speaks to collaborators, propagandists, apologists and people who felt they were just doing their job, as well as Stasi men still living a secret life, still absorbed in the possibility of another turning point back into history: a nostalgia for the ice age of totalitarianism that is surprisingly prevalent beneath the surface of east German life today. I'd argue the successes of Le Pen in France, let alone the mood beneath the regimes of China and Russia, suggest this mood is not so delusional--or exclusively Teutonic in flavour.Funder certainly gives it chilly credence here. She visits office spaces and torture rooms, has murky assignations with Stasi men at bars and churches and curtain-drawn homes, places that emanate a banal evil all their own. Human coldness is manifest in the architecture around her, in bereft public spaces, even an empty chair. Everything feels soiled.Finally she meets "the puzzle women in Nuremburg" who seek to piece back together the shredded documents of the most bureaucratized police state the world has ever known, the stories of lives that were destroyed--often covertly--by the Stasi: thickly plotted "mysteries" of lost jobs, suicide, murder and divorce, all puppet-pulled from invisible strings above people's heads. Indeed many of the victims Funder meets exist themselves in fragments and gaps, as unrestored to meaning as the shredded dossiers and files on their lives. Never to be put back together again.One of the most interesting themes to Stasiland is the way "many people withdrew into what they called "internal emigration." They sheltered their secret inner lives in an attempt to keep something of themselves from the authorities."For Funder's young and beautiful landlady Julia this defensive response has become a prison of its own. "It's the total surveillance that damaged me the worst," Julia confesses to her in one of the many startling set-pieces of the book, a kitchen scene choking with regret and claustrophobia. "I know how far people will transgress over your boundaries--until you have no private sphere left at all. And I think that is a terrible knowledge to have... That's probably why I react so extremely so approaches from men and so on. I experience them as another invasion of my intimate sphere."On that masculine point it's interesting to reflect that the GDR had the world's oldest leaders at the time the Wall was brought down and the Communist regime finally collapsed. Julia speaks of her earlier dreams that they would all eventually die off, though later she discovered they were injecting themselves with sheep cells, taking oxygen, doing anything to prolong their creepy grip on power. A female cleaner attending to the old Stasi headquarters--now a museum--speaks of how when she first arrived all the rooms emanated "the smell of old men."One feels in these irksome descriptions--along with the spidery quality beneath Funder's own encounters with aging Stasi men--the incontinency and anxiety of this culture at its very end, its repulsive dankness and needy aggression. If there is meta-psychology to the book, it's a view of the state as a people held tight in daddy's oppressive fist. It's this perspective that leads me to wonder if only a woman could fully negotiate and sensitize the political mystery of totalitarianism in the manner Funder has achieved. But perhaps that's being way too Freudian and deterministic for such brilliant inquiry into the soul of a nation at its lowest depths.By the end of Stasiland Funder is weighted by the sorrows she has heard and the death of her own mother back in Australia. Grief comes down upon her "like a cage." She leaves Germany with no great wisdoms to offer, but when she returns almost three years later it is spring, not the winter she lived through. Berlin is now "green, a perfumed city," a place she knows yet does not know at all from the winter-world she previously passed through. Though there is the vague feeling of Funder self-consciously looking for meaning in these final chapters, a flicker of her narrative control losing confidence, she still delivers a heart-rending denoument: a recognition of other, humbler human secrets, infinitely lighter than the world she submerged herself into.The queen of Australian literary journalism, Helen Garner, has rightly acclaimed this book with a cover note that states it "makes us love non-fiction." With her debut Stasiland Anna Funder has certainly announced herself as one of the leading non-fiction writers of the present day, Sydney's very own answer to Joan Dideon. Like Dideon at her early best in books like Slouching Towards Bethlehem, Funder's writing persona is taut and pale, interior and existential, yes, but absolutely enmeshed in history. We are fortunate to witness her arrival.

- Mark Mordue

Review first published online at Freezerbox (USA) on 16.06.2003. http://www.freezerbox.com/archive/art...

Published on July 18, 2013 10:22