What do you think?

Rate this book

288 pages, Hardcover

First published September 17, 2020

Gurnah’s latest novel, the magnificent Afterlives from 2020, takes up where Paradise ends. And as in that work, the setting is the beginning of the 20th century, a time before the end of German colonisation of East Africa in 1919. Hamza, a youth reminiscent of Yusuf in Paradise, is forced to go to war on the Germans’ side and becomes dependent on an officer who sexually exploits him. He is wounded in an internal clash between German soldiers and is left at a field hospital for care. But when he returns to his birthplace on the coast he finds neither family nor friends. History’s capricious winds rule and as in Desertion we follow the plot through several generations, up until the Nazis’ unrealised plan for the recolonisation of East Africa. Gurnah again uses name-changing when the story shifts course and Hamza’s son Ilias becomes Elias under German rule. The denouement is shocking and as unexpected as it is alarming. But in fact the same thought recurs constantly in the book: the individual is defenceless if the reigning ideology – here, racism – demands submission and sacrifice.

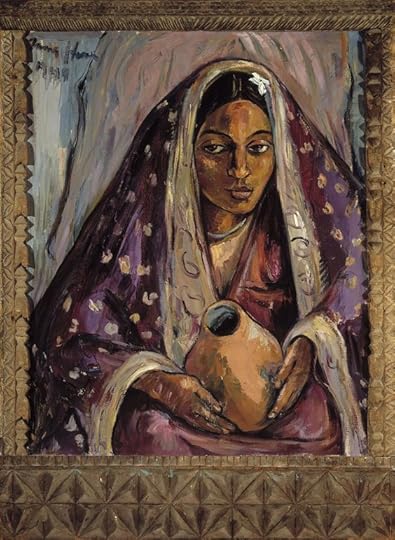

At other times she was afraid she would lose him, and he would move on as he had come, heading nowhere in particular but away from her. She had understood that much about him, from looking and listening, that he was a man who was dangling, uprooted, likely to come loose. Or at least that was what she guessed from what she saw, that he was too diffident to make the decisive move, that one day she would wait for him to come to the door for the bread money and he would not appear and would be gone from her life forever.