What do you think?

Rate this book

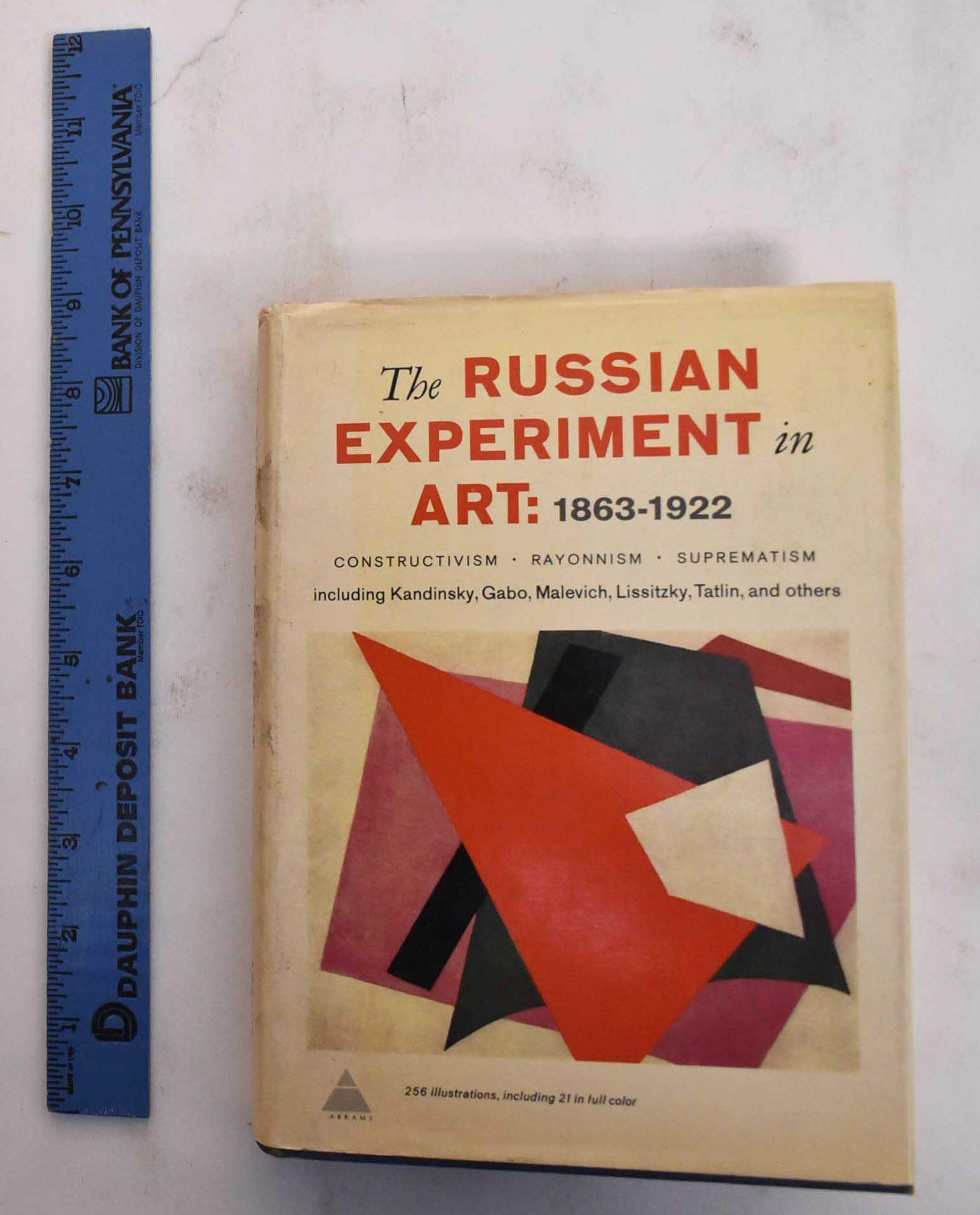

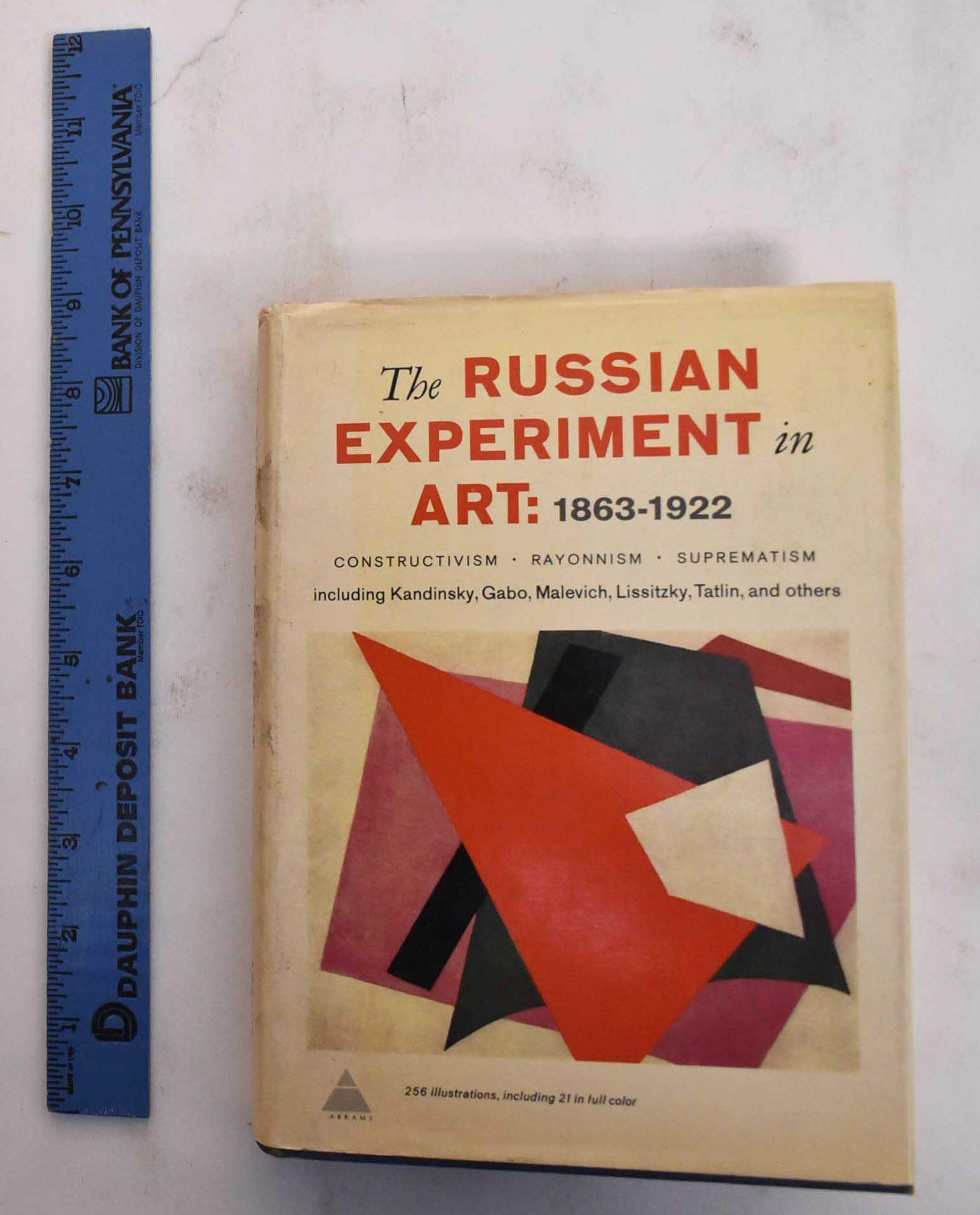

Hardcover

First published January 1, 1971

which the artist specified should be hung in the corner of the room opposite the door in the same way an icon should traditionally have been hung, do we then perceive it as a religious work - colour and form as a way of approaching God, or perhaps a piece to inspire mediation and reflection, or is Art the new religion? Is the artist God? This kind of reinvention is strongly visible in the use of colour and layout (and not just in it's mother with child motiv) in Petrov-Vodkin's "Petrograd 1918"

which the artist specified should be hung in the corner of the room opposite the door in the same way an icon should traditionally have been hung, do we then perceive it as a religious work - colour and form as a way of approaching God, or perhaps a piece to inspire mediation and reflection, or is Art the new religion? Is the artist God? This kind of reinvention is strongly visible in the use of colour and layout (and not just in it's mother with child motiv) in Petrov-Vodkin's "Petrograd 1918"  .

.