What do you think?

Rate this book

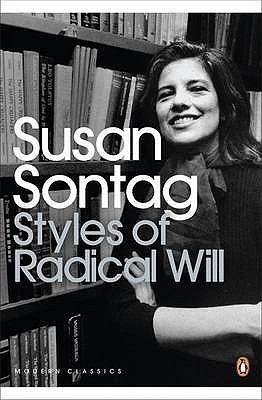

274 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1969

In my twenties if even a tenth reading of Mallarmé failed to yield up its treasures, the fault was mine, not his. If my eyes swooned shut while I read The Sweet Cheat Gone, Proust’s pacing was never called into question, just my intelligence and dedication and sensitivity. And I still entertain these sacralizing preconceptions about high art. I still admire what is difficult, though I now recognize it as a “period” taste and that my generation was the last to give a damn. Though we were atheists, we were, strangely enough, preparing ourselves for God’s great Quiz Show; we had to know everything because we were convinced we would be tested on it—in our next life.