Alan Moore tends to mythologized. This is bound to happen when you’re creating material in an era where fans are open to openly enjoying what they enjoy. Which is not an era in which we now live. Today it’s hard to tell what’s good material, because the only things people admit to enjoying are almost exclusively, to cynical eyes, common fare. Which is to say, in some eras it’s okay to like material that challenges, and in others it is not, and when Alan Moore was at his peak, he was considered one of the most challenging creators, and admired for it, and today we have Tom King, one of the most challenging creators of his era, and at least these days, he doesn’t get much love. So when he writes something like Batman: One Bad Day - The Riddler, which is a clear riff on Moore (same as Rorschach), you can compare and contrast.

Moore’s Killing Joke is famous (or infamous) for three things: it’s an origin story for the Joker, it features the Joker crippling Batgirl, and Batman apparently kills the Joker. Surprisingly, the most lasting element of the three was crippling Batgirl. For years she was wheelchair-bound, renamed Oracle, a totally different character. There’s still no definitive origin of the Joker, and he obviously didn’t die, no matter how many fans interpret the ending that way. Christopher Nolan riffed on the origin thing, brilliantly, in The Dark Knight, later. And at any rate, the comic is still viewed as one of Moore’s crowning achievements.

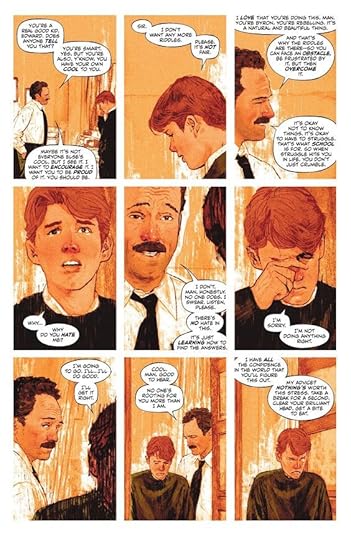

King references it directly in this. He has Riddler claim he gave the Joker the idea to attack Batgirl. He gives an origin to the Riddler. And he has Batman apparently kill the Riddler.

The question of whether any of this sticks is, at this point, moot. DC has distanced itself from a strict continuity, which is a process that began at the time Moore was writing things like Killing Joke, ironically just a few years after the “permanent streamlining” of Crisis on Infinite Earths. By allowing creators to tell bold stories (such as The Dark Knight Returns), DC was opening itself to letting the quality of the storytelling itself dictate what was publishable. For a while, there was a handy label, Elseworlds, that tucked all of it safely into little corners. But today, apart from the attempt to mask some of it under the “mature reading” Black Label, I don’t see the company making much of a fuss about it. The material is the material. King also finally had Batman marry Catwoman, but you won’t find that in common continuity.

And it doesn’t matter. So King explains the Riddler. And makes him the most dangerous man in Gotham. I’ve already seen some doubt that this is remotely possible, this despite a major theatrical release from earlier this year, The Batman, doing much the same. Some people just want to make it okay, for themselves, to dismiss whatever Tom King does.

How did he become obsessed with riddles? And what happens when he stops?

I just read the final issue of King’s Batman: Killing Time, which posits that the whole point of the story was to explain why a Batman villain plots insanely elaborate crimes. Basically, he concludes, it’s to, well, kill time. Because they can.

And that’s basically how King writes all his comics. A lot of readers just want straightforward comics, that do what comics have always done, which is to just have superheroes fighting supervillains. Period. King tends to ask questions about why they’re doing it, not just to get pesky origin stories out of the way, flimsy motivation, thin psychology. He digs deeper. He makes his characters human, capable of existing in the real world. Not just in the Marvel method of slapping on the veneer, but stepping out of the mold and observing.

Of course he still has outlandish, stylized touches. The whole point of using the Riddler at all, with this one, is that King clearly loves making up riddles, referencing history, literature, songs, and that’s his way of being theatrical, which in the hands of others is merely prancing costumes and fisticuffs, or sensationalism. And he has certainly been accused of shock tactics himself, but critics who contend he uses only shock tactics are willfully ignoring everything else, including how he uses them.

When Catwoman left Batman at the altar, or Bane killed Alfred, or KGBeast shot Nightwing, there was a grand arc working around those moments. When King transforms the Riddler into an object of terror, and spends little time on Batman himself, and yet concludes the story on an action Batman takes, it’s because he knows the reader already knows Batman, but didn’t know Riddler, so that “one bad day,” in which he meets his mother, and snaps, is the inverse of Batman, and the inverse of what Batman usually is, is what follows.

I think the storytelling is sound, as it usually is with King. I think it’ll be worth revisiting. I think people will remember it as a definitive Riddler story.