What do you think?

Rate this book

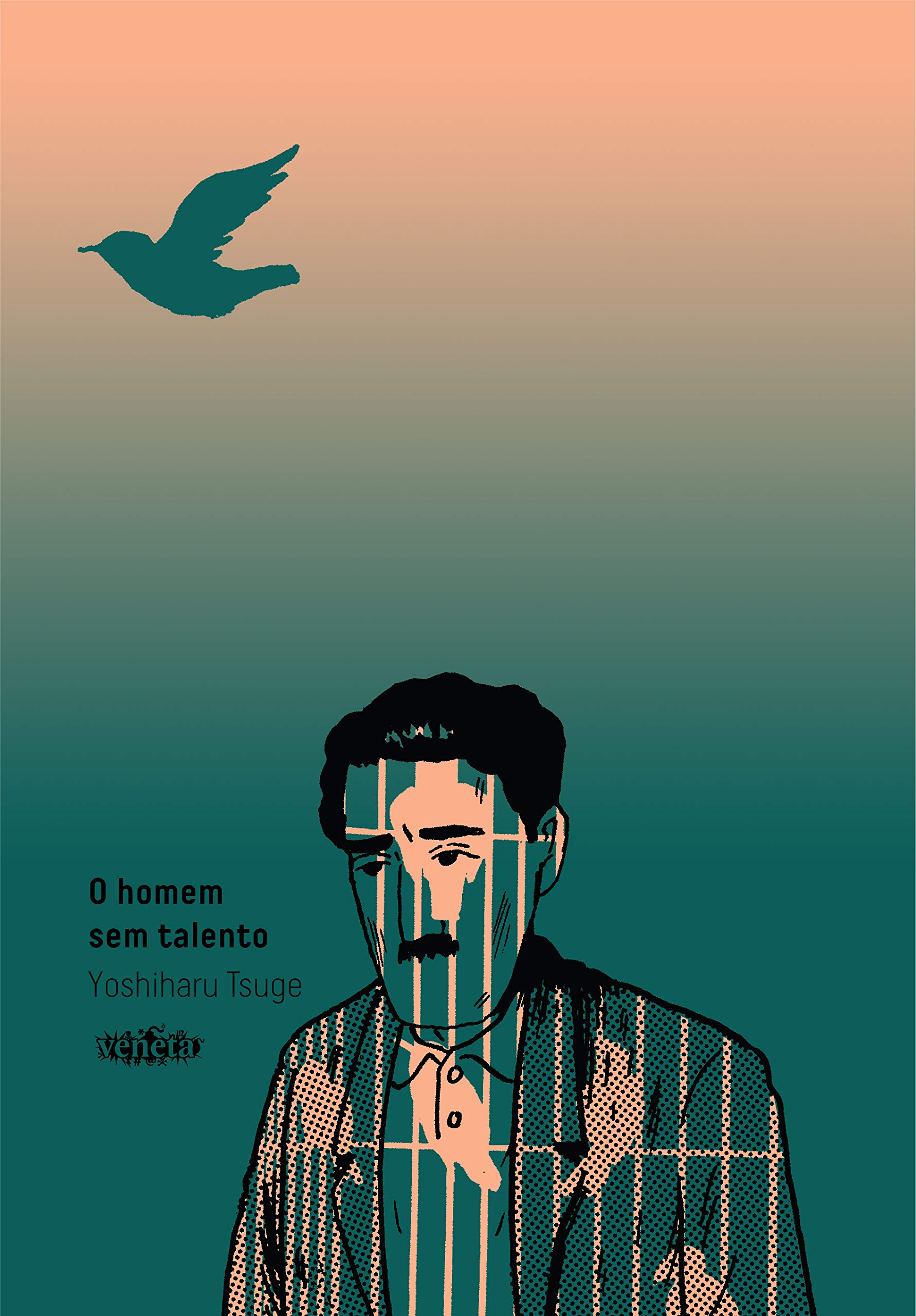

240 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 1986

'"I came to enjoy [my stories] being read as fact or close to fact, and the protagonist being imagined as the artist myself. I thought perhaps I could use the style of shishōsetsu to confuse fact and fiction, mislead people about what the artist is like, and thereby hide my true identity. Using self-concealment as a means of self-expression myself and have always preferred to hide. There is only one way to really do that, however, and that is to stop drawing altogether"—which is exactly what he did in 1987.'