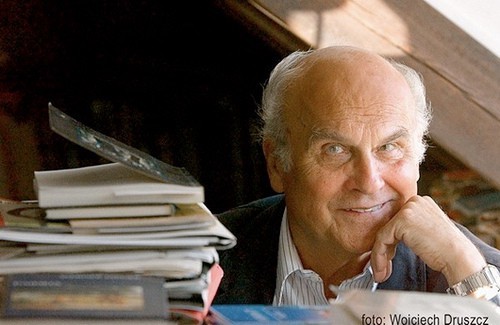

Since reading Kapuscinski's memoir Imperium—a description of his travels across the Soviet Union between 1939 and 1993—I have been an avid reader of his books. A historian turned journalist, whose mission is to "write history as it unfolds," his works provide vivid descriptions of major events of the 20th century. He focuses on Africa, Asia, and Latin America, examining their processes of decolonization and the increasing interconnectedness of various aspects of human life across the globe. Although this book does not describe major events in detail, it touches on critical topics: the rise of Pan-Africanism and decolonization in Africa, the plight of farmers worldwide, the global increase in refugees, and the profound impact of these trends on humanity.

This book is a collection of 3 interviews in which the author is questioned about various aspects of journalism, the observer's / writer's unique perspective on events, and the evolution of the profession amidst liberalization, digitalization, and the rise of large media conglomerates with political agendas. These organizations increasingly prioritize capturing attention over delivering quality content. Increasingly, the media is inundated with a torrent of images depicting catastrophic events, transforming readers into passive spectators of horrors—either voyeurs or guilty witnesses. By promoting such content, the media position themselves as moral arbiters. In this context, Kapuscinski insists that our understanding of the world is shaped less by authentic history and more by the narratives crafted by the media.

Overall, this book offers valuable insights into how this influential author observes, gathers material, and writes about the world. His ideas are increasingly relevant as we grapple with our relationship to information, truth, and the means through which we access them—be it traditional journalism, social media, or other platforms. Kapuscinski observes a crisis in literature, which he attributes not to the failings of writers but to those of readers, who no longer rise to the demands of high literature. He contends that high literature cannot exist without engaged and discerning readers. I believe the same applies to journalism and history: there are fewer and fewer individuals willing to make the extra effort to read more extensively, consult diverse sources, or engage with longer, in-depth articles. Instead, we increasingly succumb to small snippets of information, delivered through posts or tweets, which endangers both high-quality journalism and our individual thought processes.