I have been intrigued by Lacan since I first read his work (or at least, tried to read) in college, maybe it was the “purloined letter”. Around that time too I heard about Zizek and read some of his easier stuff, watched the “Pervert’s Guide” documentaries, which are great. Lacan is infamously difficult to read, and so many people end up reading people like Zizek or (this book) Bruce Fink.

It seems part of Lacan’s appeal is that he is taking Freud’s ideas and “updating” them, rooting them in language rather than the more biological / mechanical systems that Freud seemed to land on. Why does Freud need updating? He is mostly treated as a punching bag in psychology courses; he is probably read only seriously in Literature departments or by psychoanalytic practitioners. But what’s interesting about Freud is that his basic premises seem pretty uncontroversial: that we might behave in certain ways for unconscious reasons, the defense mechanisms, that early experiences are formative, this is pretty vanilla stuff for both practitioners and academic psychologists even if they don’t use those terms.

Where Freud gets in trouble, however, is that he reasons: if there are unconscious thoughts, they must live somewhere, a literal place, perhaps in the brain, perhaps as electrical (?) currents. As someone with intellectual roots in the 19th century, he is too mechanical, literal. You see this too in his discussion of penis envy, the Oedipal complex, etc. What’s funny about this is that a modern psychologist might talk about unconscious thoughts but not really worry about the implications of those claims (where is the unconscious?). They treat the unconscious as more like metaphorical language and if there’s some basis in biology that’s fine, but not of concern.

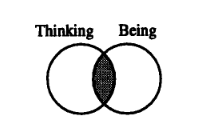

Lacan takes Freud’s ideas and makes them all about language. We are born into what he calls a symbolic order, a world of language, symbols, meaning and prohibitions that we did not get to choose. This is “good”, in that it allows us to communicate with others, live in somewhat orderly societies, be comforted in the predictability that a world of stable meaning provides. In fact, for Lacan, rejecting this symbolic order is the mark of the psychotic. This is also “bad” in that it alienates us from ourselves, makes it so that rather than having an unmediated experience of our own needs and desires we are taught to instead use these words that are not our own (the “Other’s” words) to articulate them. We have desires, but they are never fully our own, so they can never be satisfied. We are

Our relation to this symbolic order is a big part of how we understand the world and ourselves. We are, in some sense, always thinking about the symbolic as if it were this Other, a sort of person, and we worry about what “it” wants. We can think about anxiety in this way: the person at the party, plagued with social anxiety, self-aware, wondering how others see them, what they look like to others, etc. Or the over-achiever, worried about getting the right grades, into the right school, etc. The concern is with this Other: we know it wants something of us, we are not exactly sure what, and we can never quite meet it.

That’s my gloss on the clearest parts of Lacan from this book, which I have to say, varies tremendously in difficulty. The early chapters are so impressive: taking these difficult concepts and making them lucid in a way I hadn’t seen before. But the later chapters are nearly inscrutable. The chapter on sexual difference, for example, I basically couldn’t parse at all.

Fink is also less useful and less impressive in other ways. He’s less convincing when he draws on the more Freudian sounding examples for these concepts, for instance, of infants and their relations to their mothers and fathers, of people’s dreams having important meaning, of slips of the tongue that reveal everything about the person’s hangups. Maybe this is obvious to clinicians, and perhaps to some parents, but these are just not examples that resonate with me. These examples also run head first into what I feel are pretty compelling critiques of psychoanalysis, namely, that if you look at tea leaves long enough you’ll eventually make patterns that aren’t necessarily there.

Fink basically does not take seriously any of the critiques of psychoanalysis presented by more positivistic psychology, which is lame. He seems to effectively reject any kind of biological constraints on the psyche, for example. Early on, for instance, he says that for an infant, the whole body has equal potential to be erogenous, that it’s only in the symbolic order that we learn which parts “matter”, which just seems implausible. Language is powerful, but surely there are general tendencies in human behavior that seem linked to biology. And towards the end, he explicitly says that psychoanalysis is a discourse, that Science (tm) is a discourse, and that there’s no real difference between any of it. Seems, again, too strong.