What do you think?

Rate this book

360 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1952

BANQUO: It will be Rayne to Night.

1ST MURD.: Let it come downe.

(They set upon Banquo.)

Everything he took the trouble to look at carefully seemed to be bristling with an intense but undecipherable meaning: Daisy’s face with its halo of white pillows, the light pouring over the array of bottles on the table, the glistening black floor and the irregular black and white stripes on the skins at his feet, the darker and more distant parts of the room by the windows where the motionless curtains almost touched the floor. Each thing was uttering a wordless but vital message which was a key, a symbol, but which there was no hope of seizing or understanding.

Banquo: It will be rain to-night.

1st. Murderer: Let it come down.

(They set upon Banquo.)

…she felt that the place represented an undefinable but very real danger. It meant nothing, never could mean anything, to Polly Burroughs. For that to happen she would have to go back, back, she did not know how many thousands of years, but back far enough for it to denote some sort of truth. If she possessed any sort of religion at all, it consisted in remaining faithful to her convictions, and one of the basic beliefs upon which her life rested was the certainty that no one must ever go back. All living beings were in process of evolution, a concept which to her meant but one thing: an unfolding, an endless journey from the undifferentiated to the precise, from the simple toward the complex, and in the final analysis from the darkness to the light. What she was looking down upon here tonight…all belonged unmistakably to the darkness, and therefore it had to be wholly outside her and she outside it. There could be no temporizing or meditation. It was down there, spread out before her, a segment of the original night, and she was up here observing it, actively conscious of who she was, and very intent on remaining that person, determined to let nothing occur that might cause her, even for an instant, to forget her identity.Bowles’s characters exist in relation to a certain idea of eternity. Throughout their lives, there's ebb and flow- they are drawn to it and fear it, often at the same time; sometimes it seems far off and sometimes very near, capable of surging forth and obliterating individuality. But it’s out there, always, its transmissions to the soul as ambiguous as the blinking red light of a radio tower, exerting its mysterious effect, tugging at consciousness. It’s what an esoteric Russian fascist of the Silver Age might have called a “missing totality”, or what we might call nirvana, except that the mental image I associate with nirvana- a candle swiftly blown out- is too painless for Bowles. Pain and fear are inescapable elements in his stories. In fact, I would say he has written some of the most quietly unsettling scenes in literature, like the one where Port and Kit are looking out at the desert in The Sheltering Sky:

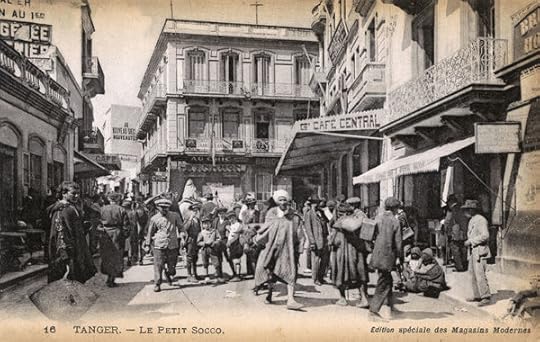

"You know", said Port, and his voice sounded unreal, as voices are likely to do after a long pause in an utterly silent spot, "the sky here's very strange. I often have the sensation when I look at it that it's a solid thing up there, protecting us from what's behind."Nelson Dyar in Let it Come Down has the same problem of not being able to get into life. He has worked at a bank in New York for over ten years, having been able to get the job in the wake of the Depression due to his father’s connections, and has been told he should be grateful. But what is gratefulness, anyway? His first act of violence is to leave his job at the bank for a job at a tourist agency in Tangier, run by an old acquaintance. Since, as Tobias Wolff wrote, Bowles’s stories “move with the inevitability of myth”, the reader never feels he could have done anything different. If it hadn’t been Tangier, it would have been Istanbul or Moscow. It’s like the story of Mr. Kurtz- being able to act with impunity brings certain aspects of himself to the surface...but they were always there, waiting. And so the real suspense in this novel is the sequence of mental events that takes place inside Dyar, which might sound very boring and abstract, except for how committed (or obsessive, depending on your view) Bowles is at describing these states precisely, lucidly. There is a logical consistency in how each slightly different state follows from the previous one; the mystery is what set the sequence in motion in the first place, which carries with it a whiff of the uncanny, of the dark matter we can observe only in its consequences.

Kit shuddered slightly as she said: "From what's behind?"

"Yes."

"But what is behind?" Her voice was very small.

"Nothing, I suppose. Just darkness. Absolute night."

"Please don't talk about it now..."

"You know what?" he said with great earnestness. "I think we're both afraid of the same thing. And for the same reason. We've never managed, either one of us, to get all the way into life. We're hanging on to the outside for all we're worth, convinced we're going to fall off at the next bump. Isn't that true?"

For a while he sat quite still in the dark, with nothing in his mind save an awareness of the natural sounds around him; he did not even realize he was welcoming these sounds as they washed through him, that he was allowing them to cleanse him of the sense of bitter futility which had filled him for the past two hours. The cold wind eddied around the shrubbery at the base of the wall; he hugged himself but did not move. Shortly he would have to rise and go back into the light…For the moment he stayed sitting in the cold. “Here I am”, he told himself once again, but this time the melody, so familiar that its meaning was gone, was faintly transformed by the ghost of a new harmony beneath it, scarcely perceptible and at the same time, merely because it was there at all, suggestive of a direction to be taken which made those three unspoken words more than a senseless reiteration. He might have been saying to himself: “Here I am and something is going to happen.” The infinitesimal promise of a possible change stirred him to physical movement…World War II is mentioned in only a few sentences in this novel, and here is one of the sentences: “They went off to Brazil, the war came, and they stayed there until it was over.” Does this mean that Bowles is, as Orwell described Henry Miller, “inside the whale”, pursuing his sick obsessions while ignoring the outside world? I don’t really think so, because Bowles, intentionally or not, in pursuing his sick obsessions, ends up capturing something about his era (and maybe ours, as well) that, if not wholly representative, seems to me at least significant. Dyar is tired of feeling like a victim. He’s overwhelmed by the burden of freedom and having to fashion a life out of a meaningless job that collapses time and suppresses his personality. A decade passes like a day. Any action- as long as it’s decisive and assertive, made with conviction- is better than this lifetime of passivity and cowardice. Lee Harvey Oswald might have felt the same way. Bowles’s presentation of a character whose options to interact with the world are reduced to two poles- sadism or masochism, to act or be acted upon- reminds me of Steps by Jerzy Kosinski (which is also, I believe, about the feeling of lost human agency in the wake of World War II). I’m also reminded of Erich Fromm’s idea, in Escape from Freedom, that sadism and masochism are two sides of the same coin, both mechanisms of escape; and that the need to escape was one of the reasons people followed totalitarian leaders like Hitler- the obliteration of the individual self in a mass movement (masochism), and at the same time permission to do violence unto others (sadism). I don’t know- could be someone’s idea of eternity.

The feeling of unreality was too strong in him, all around him. Sharp as a toothache, definite as the smell of ammonia, yet impalpable, unlocatable, a great smear across the lens of his consciousness. And the blurred perceptions that resulted from it produced a sensation of vertigo.

A life must have all the qualities of the earth from which it springs, plus the consciousness of having them. This he saw with perfect clarity in a wordless exposition—a series of ideas which unrolled inside his mind with the effortlessness of music, the exposition of geometry. In some remote inner chamber of himself he was staring through the wrong end of a telescope at his life, seeing it there in intimate detail, far away but with awful clarity, and as he looked, it seemed him that now each circumstance was being seen in its final perspective. Always before, he had believed that, although childhood had been left far behind, there would still somehow, some day, come the opportunity to finish it in the midst of its own anguished delights. He had awakened one day to find childhood gone—it had come to an end when he was not looking, and its elements remained undefinable, its design nebulous, its harmonies all unresolved. Yet he had felt still connected to every part of it by ten thousand invisible threads; he thought he had the power to recall it and change it merely by touching these hidden filaments of memory.