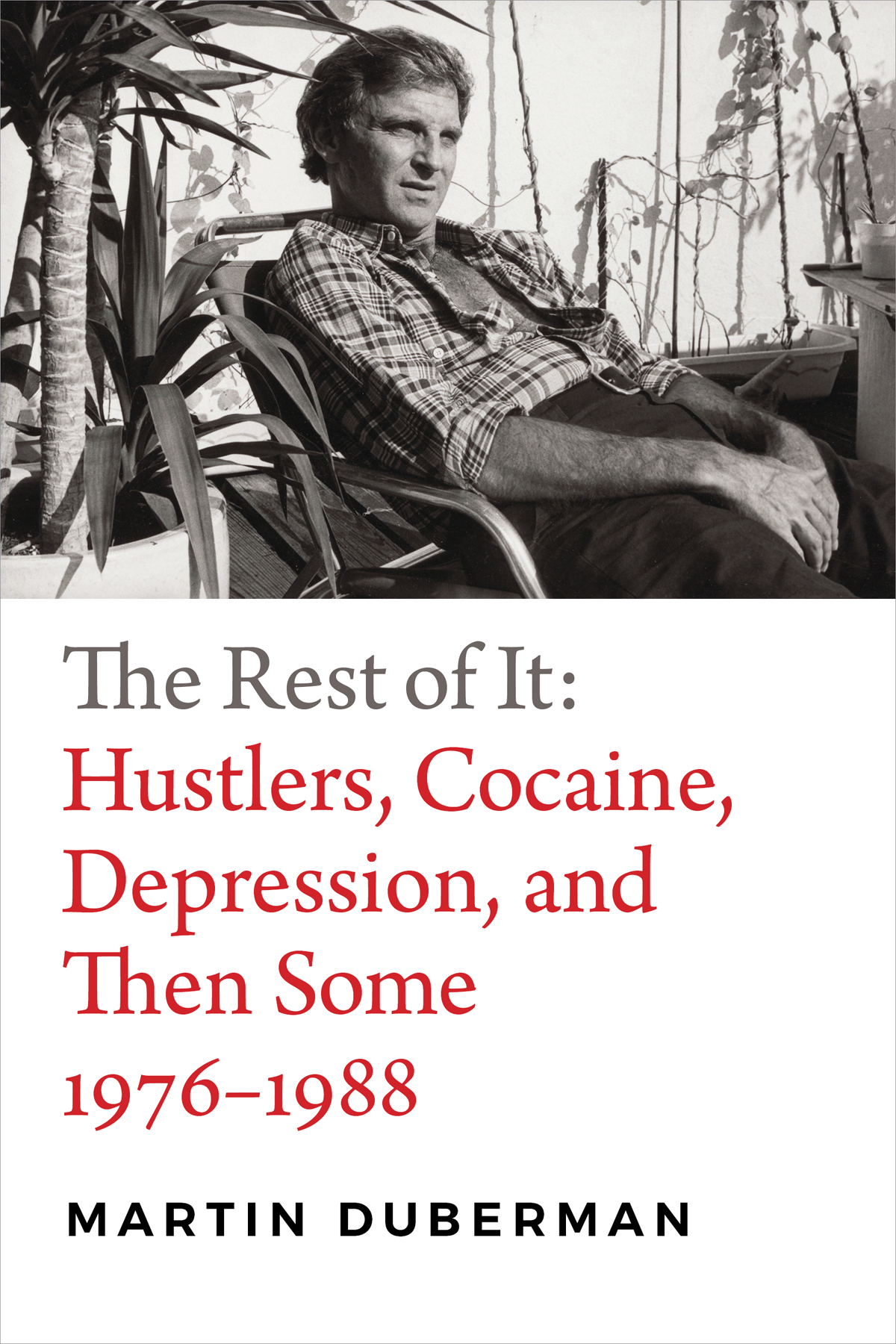

I'm a fan of Martin Duberman since reading his book, "Hold Tight Gently: Michael Callen, Essex Hemphill, and the Battlefield of AIDS." So I was very excited to read his newest memoir, "The Rest of It: Hustlers, Cocaine, Depression, and Then Some 1976—1988." In this memoir, he writes about the difficult years of his life.

Some quotes

""Coming out," most people don't seem to realize, is often a strategy for greater self-acceptance, not the thing itself."

"But self-recrimination no longer had the hold on me it once did. I felt I was at least beginning to live the life of an everyday mortal: "due" nothing, not even a long life; susceptible to the usual number of "unwarranted" disappointments, jolts, and denials; myself responsible for steering clear of people and occasions that called out my underdeveloped penchant for self assault. I would never fully learn to "settle"—my privileged upbringing guaranteed an abnormally high set of expectations—despite future defeats waiting in the wings. Yet, I was less sanguine about prospects and outcomes, less optimistic about my ability to produce a desired result. Reduced expectations were expressed in how I socialized. "

"But I didn't feel at all confident about just how the "left" the gay mainstream was these days: disco, drugs, and sex still maintained their primacy in urban, privileged, gay, white male circles, preempting political activity."

"Other organizations, such as the Gay Liberation Front, the Gay Activists Alliance, the Radicalesbians, had earlier conducted daring "zaps" and street actions that not only raised public awareness of our mistreatment but had also produced some important concrete results."

"Yet the counterculture élan that had characterized gay political groups in the immediate aftermath of the Stonewall riots, which had called for every alliance of all oppressed minorities in the struggle to sweep away entrenched structural inequalities ("intersectionality" they call it today, often assuming the concept is brand new), had all but disappeared by 1980. Zaps had given way to law briefs, sit-ins to petitions, marches to lobbying, radicalism to reformism. The building of a network of viable community institutions had been successfully begun—but they were primarily in service to the needs of a privileged white male constituency."

..."The board members who uttered these remarks (and there were others) would have angrily rejected my characterization of them as "homophobic," and that, as I wrote in my diary, is exactly the trouble with "sophisticated" liberals: "their rhetoric avoids the grosser forms of bigotry, assuming a guise subtle enough to allow them to disguise from themselves the nature of their feelings"—a feature of liberalism with which blacks have long been familiar."

"...multiple studies have shown—that LGBTQ people are more empathetic and altruistic than heterosexuals and that lesbians are far more independent-minded, and less subservient to authority, than straight women. Most gay men, moreover, unlike straight ones, put a premium on emotional expressiveness and sexual experimentation."

"One holds on to a group identity, despite its insufficiencies because for most non-mainstream people it's the closest we've ever gotten to having a political home—and voice. Yes, identity politics reduces and simplifies. Yes, it's a kind of a prison. But it is also paradoxically, a haven. It is at once confirming and empowering. And in the absence of alternative havens, group identity will for many continue to be the appropriate site for many continue to be the appropriate site of resistance and the main source of comfort.

Straight critics of identity politics employ high-flown, hectoring rhetoric about the need to transcend our "parochial" allegiances and unite behind enlightenment "rationalism," to become "universal human beings with universal rights." But to me the injunction rings hollow and hypocritical. It's difficult to march into the sunset as a "civil community" with a "common cause" when the legitimacy of our differences as minorities has not yet been more than superficially acknowledged—let alone safeguarded. You cannot link arms under a universal banner when you can't find your own name on it. A minority identity may be contingent or incomplete, but that doesn't make it fabricated or needless. And cultural unity cannot—must not—be purchased at the cost of cultural erasure."

It is a good book to read alongside Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore's "That's Revolting," David France's "How To Survive A Plague," and his earlier book I mention above. We have a lot to learn about gay history and how to create a revolution for change.

He mentions three memoirs he wrote earlier, plus this book goes into the details of writing the Paul Robeson biography, books I now want to read.