On the whole, I found this book interesting and thought-provoking – even though I disagree with the author’s premises and conclusions.

Like, I suppose, many other readers, I came to Jim Garrison’s 1988 book On the Trail of the Assassins via Oliver Stone’s JFK (1991), a film based in part on Garrison’s book. While I felt then, and feel now, that Stone’s conspiracy-theory interpretation of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963 was profoundly wrong, I found JFK to be a cinematic masterpiece.

Watching JFK on the 70-by-35-foot Cinerama curved screen at the Uptown Theatre in Washington, D.C., was an unforgettable experience. I was impressed by the film’s meticulous re-creation of period detail, its use of different film stocks to capture different points in time, and – most of all – the emotionally moving way it captured the nation’s grief and shock at the murder of the young president who seemed to embody so strongly the promise of a brighter American future.

Seeing JFK made me want to read On the Trail of the Assassins, though I went into the book feeling more than a bit skeptical. I knew that Garrison, a long-time district attorney for Orleans Parish in Louisiana, combined a record for tough prosecutions against vice and underworld figures with a reputation for being a publicity-seeker; his Wikipedia entry describes him as “a flamboyant, colorful, well-known figure in New Orleans”. I still disagree with Garrison’s ideas about the assassination of President Kennedy, but he certainly knows how to tell a flamboyant and colourful story.

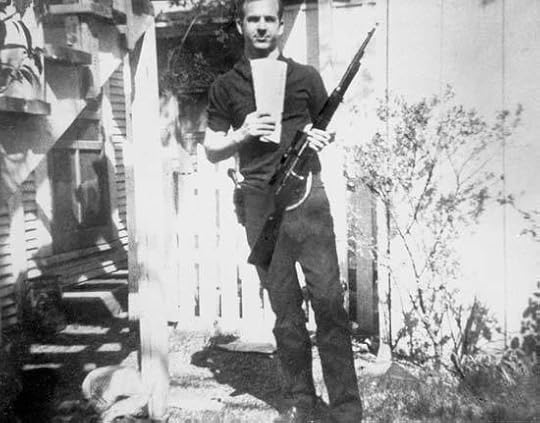

As Garrison recounts it, his time “on the trail of the assassins” began when an informant advised him that Lee Harvey Oswald might have had ties to New Orleans. What Garrison then discovered was that New Orleans was home to quite a few anti-communist Cold War ultras who had a couple of important things in common. One of those things was a rabid hatred of the late President Kennedy, who they felt had “betrayed” the Cuban anti-communists who carried out the ill-fated Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961.

Early in Garrison’s investigation, a man with the alias of “Clay Bertrand” emerged as a prominent person of interest. Garrison’s efforts to follow this lead brought up the issue of potential dangers to prospective witnesses. At Broussard’s restaurant in the French Quarter, Garrison interviewed Dean Andrews, “a roly-poly lawyer who spoke in a hippie argot all his own.” Garrison had learned that “Clay Bertrand” once spoke to Andrews about representing Lee Harvey Oswald, and Garrison wanted Andrews to furnish “Bertrand’s” real name.

Andrews engaged in one distraction tactic after another – knocking back martinis, pointing out a pretty girl in a red dress, talking jive – and then Garrison lost patience:

“I’m aware of our long friendship,” I said. “But I want you to know that I’m going to call you in front of the Grand Jury. If you lie to the Grand Jury as you have been lying to me, I’m going to charge you with perjury. Now, am I communicating with you?”

Andrews stopped eating his crabmeat and put down his fork. He was silent for a long moment, apparently saddened at the failure of his jive humor. Then he spoke….

“Is this off the record, Daddy-o?” he asked me. I nodded. “In that case,” he said, “let me sum it up for you real quick. It’s as simple as this. If I answer that question you keep asking me, if I give you that name you keep trying to get, then it’s goodbye, Dean Andrews. It’s bon voyage, Dean-o. I mean, like, permanent. I mean, like, a bullet in my head – which makes it hard to do one’s legal research, if you get my drift. Does that help you see my problem a little better?” (pp. 107-08)

“Clay Bertrand” turned out to be Clay Shaw. A New Orleans businessman with an aristocratic manner, Shaw was a pillar of the Crescent City’s business community, well-liked and popular. Garrison, therefore, would not be making any friends by going after Clay Shaw for alleged involvement in a conspiracy to assassinate a President of the United States. But Shaw did have C.I.A. contacts, and Garrison’s investigation eventuated in Shaw’s being arrested and charged, in March of 1967, with conspiracy to assassinate President Kennedy.

The Clay Shaw trial became a media firestorm, and Garrison seems to feel that he and his case were treated quite unfairly:

Some long-cherished illusions of mine about the great free press in our country underwent a painful reappraisal during this period. The restraint and respect for justice one might expect from the press to ensure a fair trial not only to the individual charged but to the state itself did not exist. Nor did the diversity of opinion that I always thought was fundamental to the American press. As far as I could tell, the reports and editorials…were indistinguishable. All shared the basic view that I was a power-mad, irresponsible showman who was producing a slimy circus with the objective of getting elected to higher office, oblivious of any consequences. (p. 200)

Garrison can believe as he believes; but as I was reading these passages, I couldn’t help reflecting that part of the job of the media, in the U.S.A. or any other democracy, is to be skeptical, to play devil’s advocate, to hold the powerful to account – including a district attorney with a controversial new explanation for one of the most notorious crimes in American history. As Garrison complained about an alleged media conspiracy to discredit him, on top of the alleged conspiracy to assassinate President Kennedy, I began to become weary of the conspiratorialism of it all.

The Clay Shaw trial, with the first public screening of the film footage that Abraham Zapruder shot on November 22, 1963, at Dealey Plaza, convened on January 29, 1969. On March 1 of that year, the jury found Shaw not guilty on all charges, after deliberating for less than an hour. It was the only time in U.S. history when an alleged JFK assassination conspirator was put on trial.

This legal reversal, and a later federal trial of Garrison on bribery charges – part, Garrison believed, of a federal conspiracy (another one!) to destroy him for his JFK investigations – left him unbowed. Late in the book, he states quite clearly what he thinks happened on that terrible November day in Dallas:

I believe that what happened at Dealey Plaza in Dallas on November 22, 1963, was a coup d’etat. I believe that it was instigated and planned long in advance by fanatical anti-communists in the United States intelligence community; that it was carried out, most likely without official approval, by individuals in the C.I.A.’s covert-operations apparatus and other extra-governmental collaborators, and covered up by like-minded individuals in the F.B.I., the Secret Service, the Dallas Police Department, and the military; and that its purpose was to stop Kennedy from seeking détente with the Soviet Union and Cuba and ending the Cold War. (p. 336)

Those who are disposed to believe as Garrison did will probably continue to do so. Those who do not believe Garrison will continue to feel as they have always felt about the assassination of President Kennedy. Garrison’s book – subtitled My Investigation and Prosecution of the Murder of President Kennedy – will probably not change many minds, one way or the other.

For my part, I have visited the Sixth Floor Museum in Dallas (it presents the history of the assassination and its aftermath responsibly and with dignity), and I have looked out the window from which Lee Harvey Oswald is said to have fired the fatal shots. I still believe that Oswald committed that dreadful crime, and that he acted alone. Sometimes, unfortunately, a misfit loser with delusions of grandeur can change the course of history for the worse, all by himself. It has happened before. Sadly, it will happen again.

If you believe in the existence of a JFK assassination conspiracy like what Garrison describes in his book, I respect your opinion. I simply don’t share it.

Garrison lost his district attorneyship in the aftermath of his bribery trial, but he remained a colourful character on the New Orleans scene until his death in 1992. Look fast in the scene where Dennis Quaid’s police-detective character goes on trial in the New Orleans thriller The Big Easy (1987), and you’ll see Jim Garrison playing the trial judge. Garrison also has a fun cameo in JFK, playing, of all people, Earl Warren! Yes, Supreme Court Justice Earl Warren, the very person who ran the commission whose findings – that Oswald acted alone – Garrison worked so hard to try to discredit.

I know that I’ll want to watch JFK again. Kevin Costner as Garrison gives a heartfelt performance – the best of his career, I think – and his work is complemented by those of one of the best ensemble casts ever assembled: Kevin Bacon, Tommy Lee Jones, Gary Oldman, Sissy Spacek, Joe Pesci, Jack Lemmon, Walter Matthau, Donald Sutherland, Ed Asner, Brian Doyle-Murray, John Candy, Sally Kirkland, Vincent D’Onofrio, Lolita Davidovich, and John Larroquette (with Martin Sheen narrating). I don’t know that I’ll read On the Trail of the Assassins again. But it can be a salutary thing, a good intellectual exercise, to read the work of a writer with whom one disagrees.