Again some guys who did not understand their Nietzsche properly

On May 21, 1924 the highly intelligent students Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb killed a 14-year old neighbour, Bobby Franks, hitting him with a chisel and choking him by putting a sock into his mouth. Their only motive was sheer vanity at the thought of committing a perfect crime and their conviction, falsely aquired from a misreading of Nietzsche, that they were “supermen” to which human laws would not pertain.

Five years later, the English playwright Patrick Hamilton made their story into a drama, setting the scene in London. His anti-heroes, the two students Brandon and Granillo strangle a fellow-student and conceal his body in a large chest. In order to revel in their ghastly deed, they invite several people, amongst whom the father and aunt of their victim, for a dinner party and actually have these people partake of their sandwiches and caviar from the very chest that contains the assassinated young man’s remains. One of their guests, Rupert Cadell, a somewhat jaded poet, however, smells the rat and tries to hunt them down.

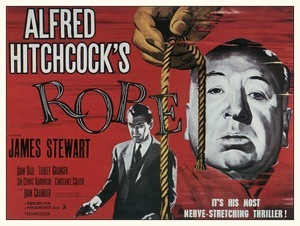

This story will seem familiar to most of us from the Hitchcock film of 1948 starring James Stewart, but the play stands in its own right, as it differs in many points from its adaptation for the screen by Hitchcock. For a start, most of the characters in the play have not known each other before meeting on that macabre occasion. Then we can hardly find anything pleasant about the main characters, as even Cadell is far from being the dandified cynic who, in his heart of hearts, is a likeable and decent man, as played by Stewart. Unlike the film, the play also provides some clues with the help of which Cadell traces down the morbid mystery. One major plus of the play is that its dialogues are more refined and nuanced than those of the film, e.g. it does not have the conversation in which Cadell, in a rather playful manner, enlarges on his salon nihilist theory of the rightfulness of murder. Instead we find him demasking common moral tenets according to which murder in times of peace is socially rejected, whereas in times of war it is even rewarded. At this stage it becomes clear that much of this character’s disillusionment and bitterness are a consequence of the atrocities he went through in World War I.

The play contains some fine scenes of suspension, although the characters lack the typical Hitchcock esprit, and it also makes you think about moral values and how they are influenced by social prejudice, e.g. the positive image of killing in times of war, or for other seemingly “noble” motives. It is just a bit of a pity that Nietzsche is dragged into this sordid affair again.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hukbu...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hukbu...