What do you think?

Rate this book

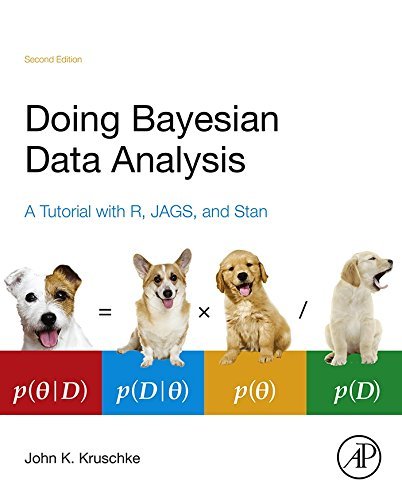

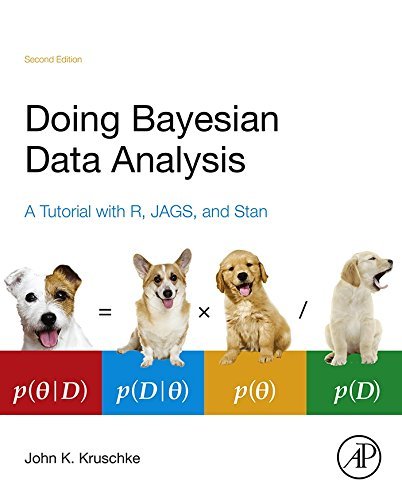

There is an explosion of interest in Bayesian statistics, primarily because recently created computational methods have finally made Bayesian analysis obtainable to a wide audience. Doing Bayesian Data Analysis: A Tutorial with R, JAGS, and Stan provides an accessible approach to Bayesian data analysis, as material is explained clearly with concrete examples. The book begins with the basics, including essential concepts of probability and random sampling, and gradually progresses to advanced hierarchical modeling methods for realistic data. Included are step-by-step instructions on how to conduct Bayesian data analyses in the popular and free software R and WinBugs. This book is intended for first-year graduate students or advanced undergraduates. It provides a bridge between undergraduate training and modern Bayesian methods for data analysis, which is becoming the accepted research standard. Knowledge of algebra and basic calculus is a prerequisite.

New to this Edition (partial list):

There are all new programs in JAGS and Stan. The new programs are designed to be much easier to use than the scripts in the first edition. In particular, there are now compact high-level scripts that make it easy to run the programs on your own data sets. This new programming was a major undertaking by itself. The introductory Chapter 2, regarding the basic ideas of how Bayesian inference re-allocates credibility across possibilities, is completely rewritten and greatly expanded. There are completely new chapters on the programming languages R (Ch. 3), JAGS (Ch. 8), and Stan (Ch. 14). The lengthy new chapter on R includes explanations of data files and structures such as lists and data frames, along with several utility functions. (It also has a new poem that I am particularly pleased with.) The new chapter on JAGS includes explanation of the RunJAGS package which executes JAGS on parallel computer cores. The new chapter on Stan provides a novel explanation of the concepts of Hamiltonian Monte Carlo. The chapter on Stan also explains conceptual differences in program flow between it and JAGS. Chapter 5 on Bayes’ rule is greatly revised, with a new emphasis on how Bayes’ rule re-allocates credibility across parameter values from prior to posterior. The material on model comparison has been removed from all the early chapters and integrated into a compact presentation in Chapter 10. What were two separate chapters on the Metropolis algorithm and Gibbs sampling have been consolidated into a single chapter on MCMC methods (as Chapter 7). There is extensive new material on MCMC convergence diagnostics in Chapters 7 and 8. There are explanations of autocorrelation and effective sample size. There is also exploration of the stability of the estimates of the HDI limits. New computer programs display the diagnostics, as well. Chapter 9 on hierarchical models includes extensive new and unique material on the crucial concept of shrinkage, along with new examples. All the material on model comparison, which was spread across various chapters in the first edition, in now consolidated into a single focused chapter (Ch. 10) that emphasizes its conceptualization as a case of hierarchical modeling. Chapter 11 on null hypothesis significance testing is extensively revised. It has new material for introducing the concept of sampling distribution. It has new illustrations of sampling distributions for various stopping rules, and for multiple tests. Chapter 12, regarding Bayesian approaches to null value assessment, has new material about the region of practical equivalence (ROPE), new examples of accepting the null value by Bayes factors, and new explanation of the Bayes factor in terms of the Savage-Dickey method.746 pages, Kindle Edition

Published November 11, 2014