"On monuments to the dead, it says that Andre, Celestin, and so many others 'died for France'; in that case, these people lived against her, and so do those who have succeeded them and who perpetuate their obsessions."

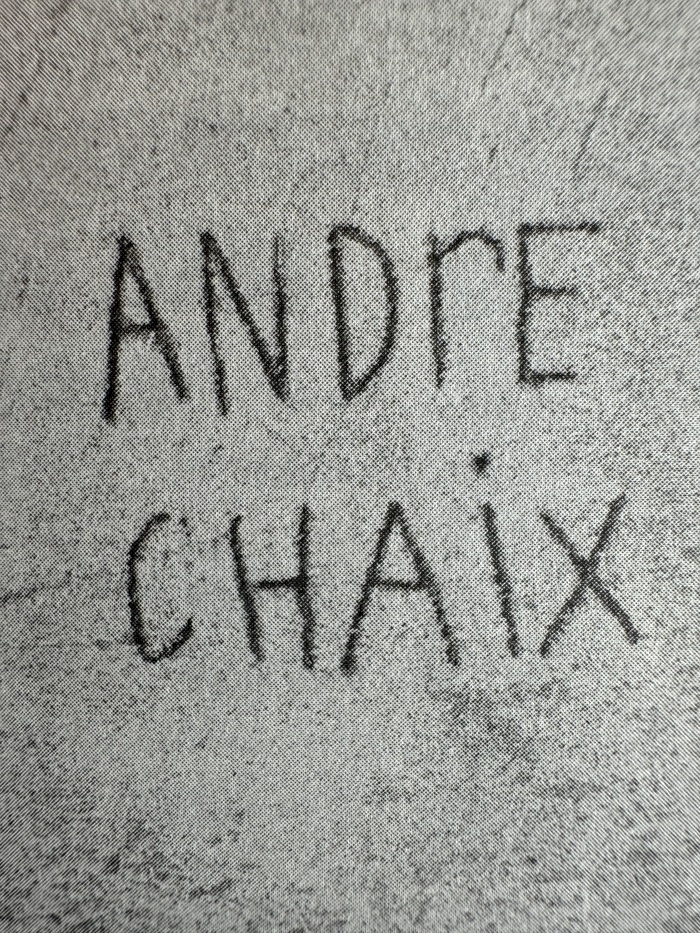

This is a pedestrian 'novel' about researching the scant evidence of the life of Andre Chaix, a young resistant whose name was carved into the outer wall of the author's newly-purchased home. Self-indulgent, undigested, and reminiscent of reading over someone's shoulder ambling through Wikipedia - but at each branch, the guy picks the less interesting link. His rehashings of 1960s 'who goes Nazi' "experiments" were particularly grating, for their irrelevance and for their obviousness. It's 2025 in the Western world... there are overt Nazis all about. Navel-gazing about the complacent conformity of ordinary people is only the inverse of 'not guilty / we were just following orders'.

Le Tellier quote Burke as an epitaph: "When bad men combine, the good must associate; else they will fall, one by one, an unpitied sacrifice in a contemptible struggle." But this book isn't about association, far less politics. It's about glazing the memory of a lonely, ineffectual death in the service of Good, until the author feels that "he can always give a brotherly smile to your name on the wall." On returning to it that line is even more insulting than on first reading. He displays only a sentimental curiosity about the facts of Chaix's tragically short life: indulging his own imaginings and digressions, he does not stop once to ask himself about the motivations or commitments of this brave young man, much less seek any but the most disrespectful resolution. One gets the sense that Le Tellier might think Chaix lucky, his death justified because, though his life was cut tragically short by German bullets during the war's bloodiest month, it someday came to the attention of the intrepid M. Le Tellier. Homer's Achilles warns us that the life of the humblest man is worth more than the glory of the most famous shade; M. Le Tellier isn't so sure.

Akin to Binet's far superior but similarly-flawed HHhH, there's something pathetically resigned about dwelling too freely in the clear-cut 1940s, especially in an autofictional mode like this. We must face up to our own times, and we cannot earn the respect or the brotherhood of our forebears by meekly admiring their righteousness. The world does not stay saved; and immersing oneself in imaginary communion with a victim of its last saving, while it cannot harm the dead, hardly redounds to the credit of the living.

Remember Auden and despair, and let that despair drive you to act anew:

To save your world you asked this man to die:

Would this man, could he see you now, ask why?