What do you think?

Rate this book

208 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 2008

JOHNSON: Now then, Cormac, where were we. Chapter Eight; new paragraph. Quote: ‘Edward Morley, a chemist at neighboring Western Reserve University, was as meticulous a scientist as Michelson. The two men agreed that it would be pointless to make another attempt to detect the Earth's absolute motion unless they could first confirm Fresnel's hypothesis – that the celestial backdrop is fixed in space with only pinches of aether dragged along by transparent objects.’ Just read that back for me, would you?

MCCARTHY: The sky was clear and Michelson's heart was clear and only in the far west the clarity was broken where the last cloudbank bled over the land like a jugged hare; and yet all was in motion, heart, blood and sky, spiraling forever into the measureless void and haling the ether along with it like the caul over a miscarried infant's soft and innocent head. Innocent? Nay – rife with original sin.

Michelson spat on the ground, and the parched land accepted his meager gift.

—Reckon Fresnel might have been on to something after all, Morley said, studying the westering sun.

JOHNSON: Perhaps we should take a break.

* The ways that professors steal credit for work that their students have done – or that their students lay greater claim to that work their advisors believed they deserved (e.g., Robert Millikan and Harvey Fletcher).I doubt that Johnson hoped that I would draw these conclusions, although he probably would not have been surprised either. Science is a very human endeavor.

* The important roles of scientific rivals or supportive colleagues in the progress of that science (e.g., Galvani and Volta): Though neither man could quite see it, their experiments complemented each other, for they were dancing around a single truth (p. 74). Conversely, Lady Ada Lovelace was an effective and important muse to Michael Faraday, and Alexander Graham Bell was an important benefactor to A. A. Michelson.

* It's not just the observations that matter, but what you do with them (e.g., Lavoisier, Priestley, and Scheele). Could Priestley and Scheele recognize their data's meaning? (Of course, data doesn't come with clear labels.) Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier did.

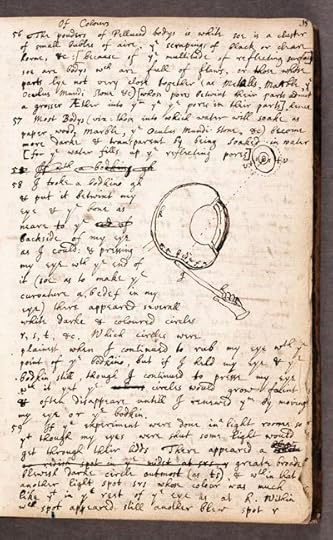

* The experimental mindset is central and essential to the work and to the personality of the researcher, illustrated in the story of Lavoisier's execution by guillotine – surely hyperbole. He wondered whether death by guillotine was painless. Lavoisier tested this hypothesis, so the story goes, by beginning to blink his eyes as soon as he felt the blade touch his neck and as many times as he could, while an assistant in the crowd would count his blinks. Such a mindset touches everything. Or, as in the drawing above, Sir Isaac Newton was so intensely curious about vision and light as to poke a stick in and around his own eye to observe what happened.

* Memory is often treacherous. Johnson described several cases of clear misremembering, as in Wilhelm Roentgen's first reports of x-rays of the hand, which so excited Robert Millikan that he misremembered this report as happening at the German Physical Society on Christmas Eve, but it instead took place in the following January.

* But Johnson described other cases of "misremembering," which seem much more to be "cooking the books," where researchers appeared to comb their data for support for their preconception (e.g., Robert Millikan).

*Or in yet other cases, the experimental method appears to be "smoothed over" rather than an accurate description of the initial research. Stillman Drake, for example, argued that Galileo probably sang in order to assess time in his experiments, but “Even in [Galileo's] day, it would have been foolish to write, ‘I tested this law by singing a song while a ball was rolling down a plane, and it proved quite exact.’" (p. 15).