What do you think?

Rate this book

256 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2006

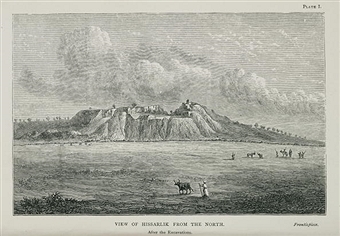

Do you see there, Sophia, that bay? That is where the princess Hesione was exposed to the attacks of the sea-monster sent by Neptune. Do you see that promontory of black rock? That is where Hercules saved her.No qualification, or caveat regarding the veracity of the story…for Obermann, it happened exactly the way Homer said it did. It is truth and it colors everything about him.

'In your latest report to The Times, Mr. Obermann, you mentioned a tower.'“No Matter. We have a different vision.” That sentence sums up Obermann perfectly.

'Of course. It is there? Do you not see it rising out of the earth?'

'I see a piece of wall. Nothing more.'

'Look again, Professor. It is the tower that Andromache ascended because she had heard that the Trojans were hard pressed and that the power of the Achaeans was great.'

'I know the passage, Mr. Obermann. But I’ll be darned if I can see the tower.'

'No matter. We have a different vision.'

'But one thing does puzzle me.'I don’t think you will have ever come across a character quite like Herr Obermann. Deeply moving, deeply flawed, even dangerous, but so engaging you will not be able to look away and he will almost make you wish you could see the world through his eyes.

'Yes?'

'In your report to The Times you say that the palace was built on the summit. But it is here, on the north-west ridge.'

'It is necessary to inspire the readers of your newspapers. To give them dreams. That is my, idealism, Professor. In my imagination I witnessed the gleaming palace surmounting all.'

There are many Turks who believe that the capture of Constantinople was a just vengeance for the fall of Troy. The Greeks were at last made to pay for their perfidy. [loc. 2376]

Reread: my review from 2010 is here. I remembered nothing at all about this novel! Apparently I purchased a paperback copy in 2007: as with almost all of his other novels, no Kindle edition is available.

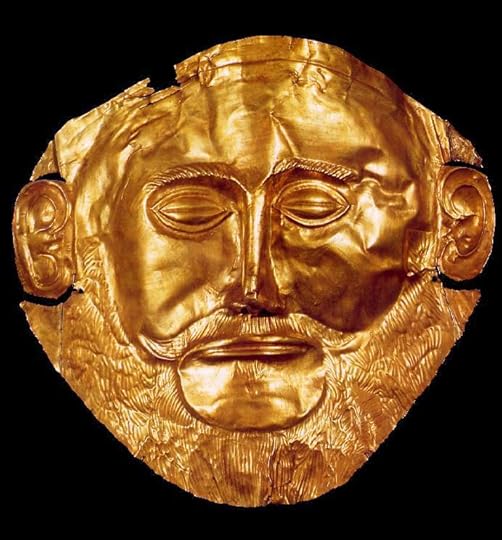

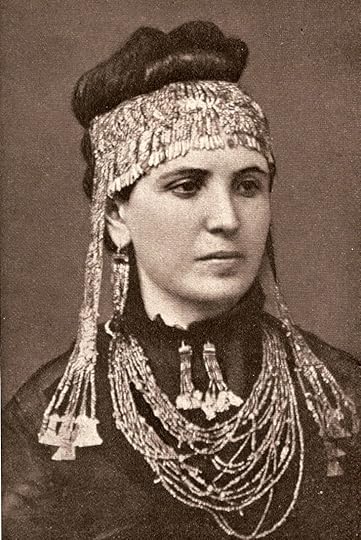

Ackroyd bases his novel on the life of Heinrich Schliemann, who first excavated Troy, and his marriage to a much younger woman, a Greek (famously chosen on the basis of a photograph and 'Homeric spirit'). Ackroyd's fictional archaeologist is named Heinrich Obermann, and he has all of Schliemann's flaws and more: he's avaricious, racist, an intellectual fraud and a bigamist. He goes by his gut feeling rather than solid archaeological methodology, and he refuses to accept evidence which contradicts his own opinions.

We see him from his wife Sophia's perspective: she doesn't love him, but is determined to make the marriage work. She finds purpose in the excavation of the ancient city, and colludes with Obermann's deceits -- until she discovers that he has lied to her, as well as to everyone else.

I liked the way that Ackroyd wove in some of Schliemann's tall stories (smuggling Priam's treasure away from the site in Sophia's shawl) and I found Obermann's fate rather more satisfactory than Schliemann's: hubris and nemesis.