Ping-ponging between photorealistic naturalism and frankly Miyazaki- (and Moebius) inspired fantasy interludes, The Nao of Brown is a smart, layered novel about the relationship between reality and fantasy—in this case the fantasies, both violent and romantic, of Nao Brown, a young British woman of partly Japanese descent, who struggles with OCD and her own murderous daydreams. Nao is a good person, and desperately needs to keep reminding herself of that fact, but she cannot trust herself; she so often imagines hurting or killing the people she is with. To keep these terrifying fantasies at bay, Nao resorts to compulsive mental routines that are meant to distract and redirect her thoughts (memories of Justin Green's Binky Brown cannot help but come to mind, and indeed Dillon pays homage to Green several times). She has other fantasies too, such as her crush on a washing machine repairman with a complex and poetic soul, a man she likes at least partly because he resembles a favorite character of hers from anime. As she pursues her fantasy of being with this man, she ignores obvious signals from another: the owner of the toy and collectibles shop where she works.

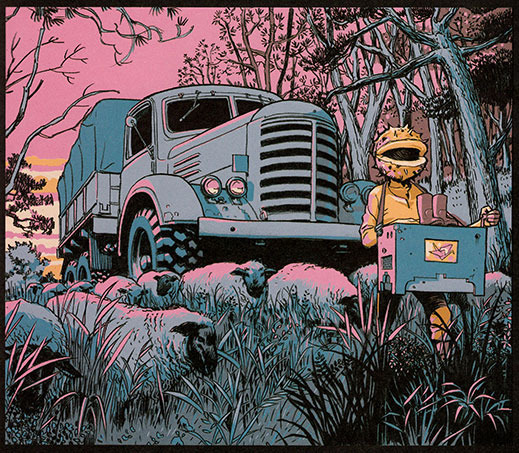

While these romantic possibilities, or entanglements, drive the plot, Nao's involvement with a Buddhist community center and her often frustrated practice of Buddhist meditation inspire fascinating digressions, detours rather, in the narrative. At the same time, the fantasy interludes (which tell an animistic fairy tale about a sort of tree spirit that recalls Miyazaki's eco-fantasies and the Brothers Grimm equally) take the story and art in still other directions. The important thing here, though, is Nao's relationship with her own mind, and her search for calm and self-mastery in spite of her disability. The Buddhist reflections play a large role in putting that struggle into perspective.

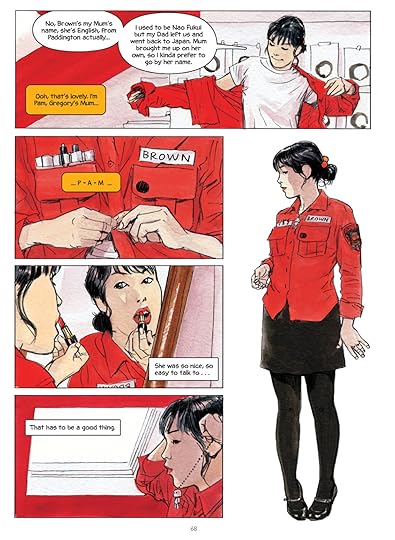

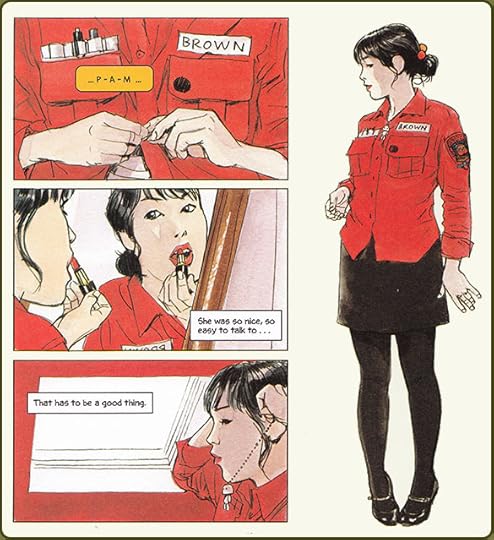

Visually, atmospherically, Nao is often brilliant, usually gorgeous, and a bravura performance overall. Dillon conjures London, and scenic interiors, with seeming effortless expertise, and the characters are distinctive and expressive. He handles layout ingeniously, using formal conceits (e.g. a split panel) cleverly but unobtrusively. His photorealistic drawing is nicely set off by a lightness of touch; the linework has an open, delicate quality, enhanced throughout by the lovely watercolors, which let the whiteness of the page shine through and never cloy or distract. The fantasy sequences are different in style: rendered more lavishly, with something approaching the clear-line aesthetic of Moebius or Cosey and full, saturated, traditional BD-style color, they pop out immediately from their surroundings. Presumably Dillon's drawing has been extensively photoreferenced—facial expressions are so acutely, precisely right that they suggest long study—but only in the climactic struggle between Nao and her object of desire, the repairman, does this quality become distracting, almost grotesque, perhaps because it's supposed to be (this is where the relationship between the two characters tips into outright confrontation, and buried secrets come screaming to the surface). It's there, in the home stretch, that Dillon sacrifices charm in a bid for realism, depth, and climax.

Nao enthralled me on several levels; it kept me up late one night when I was supposed to be sleeping. I have to say, however, that the book's attempted climax and resolution didn't quite come off. Sudden lurches in the plot, as [SPOILER ALERT] Dillon leaps years into the future to show us Nao's self-transformation, do not explain enough. That Nao's perspective on life is transformed when she is struck by a car—a sort of satori or Paul-on-the-road-to-Damascus moment, and at precisely the point of greatest stress in the story—strikes me as too convenient a leap. The repairman's own deep backstory, hinted at earlier, is simply spilled in several pages of prose, abruptly inserted (mind you, I'm not against the use of such devices in comics in general; there is no reason prose and comics cannot work together powerfully, as in, e.g., books by Phoebe Gloeckner or Posy Simmonds). There are several delightful and humane surprises in the book's conclusion, and they make me want to like that conclusion more, but Dillon's plot-rigging is too patent there, too rushed. Long and rich as the novel is, it needed to be even longer to earn the kind of warm emotive payoff it asks for.

It remains a rich character study, a beautifully made book, and a delightful confirmation of how comics can redefine the relationship between reality and fantasy. But, oh, the unearned leap of the ending.