When I wanted to acknowledge the centennial of the worst pandemic in history (yes, far worse than bubonic plague), I didn't know two new books had been released in 2018 by Catharine Arnold and Jeremy Brown, on the 1918 global flu pandemic. It was difficult to find Alfred Crosby's 1989 historical work, so I settled on Kolata's 1999 popular account, since I like her breezy yet scientifically accurate style. Funny thing is, based on synopses of the Arnold and Brown books, our knowledge of the 1918 flu has not expanded much in the 20 years since Kolata wrote this book.

The author begins her book by mentioning several funny things. She had a lifelong interest in health and infectious diseases, yet knew almost nothing about the pandemic. The more she probed, the more her ignorance made sense. The media in 1918 was strangely silent, and the victims' families and public health officials seemed almost embarrassed to talk about it, a scenario similar to the 1970s-80s early reaction on AIDS. Crosby and Kolata both attribute this to psychological numbing and wartime censorship -- the world had just ended a devastating global war, and no one seemed ready to confront another atrocity.

This book is not a definitive historical guide to what happened in 1918. One could turn to Crosby or Arnold for that. Instead, it operates as numerous detective stories, taking place immediately following the flu's decline, and in the 1950s, 1970s, and 1990s. Kolata does a good job of weaving these stories together, particularly the efforts to find bodies of victims frozen in the permafrost in order to gain virus samples. Along the way, Kolata talks about the swine flu vaccine misfire during the Ford administration in 1976, and the public health crisis over live chickens in Hong Kong in the late 1990s. Sometimes she goes far afield, in describing Johan Hultin's Alaska adventures in the 1950s, but her journeys are usually enjoyable ones. Other times, her character assessments seem a bit harsh, like her easy dismissal of Kirsty Duncan in the Spitzbergen expedition. (Duncan was appointed Minister of Science in Justin Trudeau's government in Canada, so one could say she had the last laugh.)

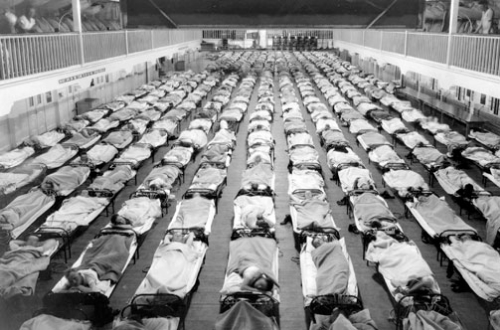

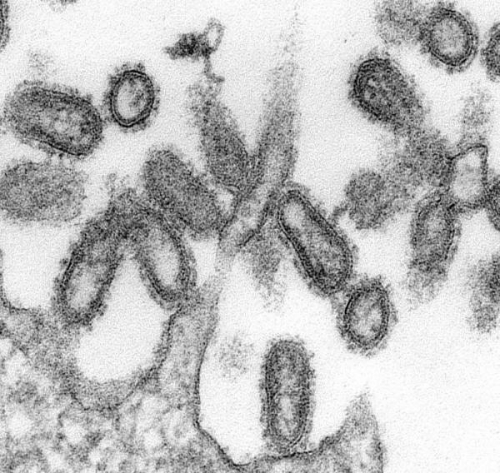

What emerges from Kolata's hopscotching across the decades is that science uses the tools available at the time, and often has to retrace its steps as new tools make it possible to conduct studies that were impossible decades earlier. But gaining clarity does not always mean gaining deeper understanding. We know that the 1918 flu was an H1N1 bird flu derivative, we know details of its protein coat, but we don't know why it was so astonishingly virulent, killing close to 100 million people worldwide. Kolata ends her book, not with a series of revelations, but with a series of new questions raised as researchers continued their viral studies at the end of 1999. The last possibility she raises turns out to be one that many scientists accept today: the strain of the virus itself was not particularly aggressive, since it arrived in two waves in early and late 1918 (and perhaps even in 1916-17 in France). Rather, most deaths were caused by an overreaction of the body's immune system, creating a cytokine storm that led to total respiratory failure.

We all now that the rapid mutation of the flu virus makes the annual flu vaccine offered by health authorities a crapshoot at best, though the vaccine is certainly better than nothing. But health authorities also must look at antibody histories of those receiving flu shots, to see if maybe a vaccine, or a particular flu strain, could trigger the kind of cytokine storm that led to a pandemic in its own right. A century later, we are still not close to unlocking all the mysteries of the 1918 flu. And our ability to avoid a future pandemic depends on our increasing our understanding fairly quickly. The problems of the 1976 vaccine show we must avoid making costly errors, as well.