What do you think?

Rate this book

I had invited Baxter to come give a reading at the university at which I then taught, and he and I had spent the day doing the usual classroom-visit stuff. Now we were driving the rain-slick streets of Cleveland, having just come from a bookstore where Baxter had signed copies of his then-new novel "Shadow Play."

Somehow we got started talking about writers who rarely get taught anymore or even get talked about much but who are better than many of those writers who do. My candidates were people like John Dos Passos, Willa Cather, Richard Yates, and Peter Taylor. Baxter's list was smarter and more obscure. I don't remember everyone he mentioned, only that when he mentioned William Maxwell and I lied and said, "Gee, that name rings a bell," Baxter's eyes got big.

"Turn the car around," he said. "Excuse me?" "Go back to thatbookstore," he said. "If they have a copy of "They Came Like Swallows," I'll buy it for you."

Baxter had heretofore struck me as forthrightly sane, in that peculiarly midwestern way. I looked at my watch. "I don't know," I said, meaning that the time for Baxter's reading was closing in, and we had dinner reservations. "Won't take but a minute," he said.

And so I threw my car into a U-turn and we went back. The store did not have the book or anything at all by William Maxwell. "I'll read it," I said. "I promise." He nodded. We were midwestern men who had publicly expressed and heard expressed our passions. Time to go get a nice meal.

William Maxwell may be the definitive writer's writer. He's a masterful, accessible writer whose name comes up frequently in writers' shoptalk. He's also been a great friend to and booster of other writers. From 1936 to 1976, he was a fiction editor at The New Yorker, which allowed him to aid and abet the writing careers of such giants as John O'Hara, John Cheever, Vladimir Nabokov, J. D. Salinger, Eudora Welty, Frank O'Connor, Mary McCarthy, William Carlos Williams, Tennessee Williams, and John Updike.

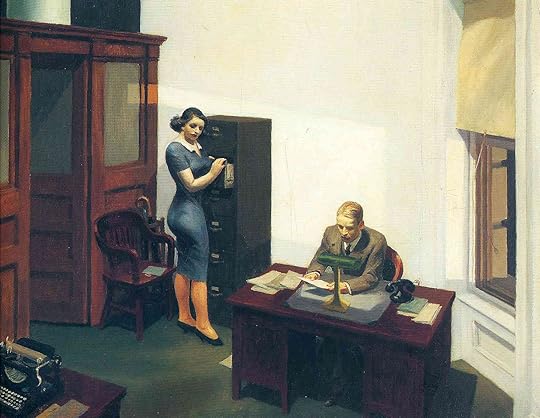

Unlike most of the authors he edited (including all of the above), Maxwell was an American midwesterner. He was born and raised in Lincoln, Illinois, and his books are profoundly midwestern full of unquaint farms, befuddled dogs, sensitive paperboys, earnest churchgoers, and disappointed old people. His work is wildly emotional without ever on the surface seeming to be so. Even his publishing history is humble in a midwestern way; Maxwell published his own acclaimed short stories for 30 years before he agreed to publish his first collection (OVER BY THE RIVER, which came out in 1977, right after he retired from The New Yorker).

I did read "They Came Down Like Swallows," a sharply observed, unsentimental child's-eye view of his mother's dying, and I admired but for some reason did not fall in love with the book. The same strange effect that tempers passion in books you are assigned to read for a class can affect books pressed upon you with evangelical zeal (this doesn't stop me from evangelically pressing books on people). I blame myself.

When Maxwell's (highly recommended) collected stories, "All the Days & Nights," came out in 1994, reviewers stood to write benedictions for the career of the octogenarian Maxwell. These raves, I fear, made readers avoid Maxwell's book. Nobody likes a critics' pet. It's like being outside of a club you didn't know existed and being invited in by snooty people who wouldn't talk to you in high school or, worse, who live in New York City. At least that's how it is if you are an American midwesterner.

This attention, though, prompted Vintage to reissue most of Maxwell's books, and it was with one of these, the magnificent short novel "So Long, See You Tomorrow," that I became a Maxwell acolyte. I am, for this book's sake, willing to turn cars around to buy copies for new friends.

The book concerns a murder on an Illinois farm in the 1920s and, principally, that murder's consequence on the livingthe families in particular, the town in general. The book is told, a half-century later, from the point of view of a friend of the murderer's...

Audio Cassette

First published January 1, 1980

"Two friends on a scaffold, with no final goodbye,

One sank into silence, the other passed him by"

“It happened the way all tragedies happen: not at once, but inch by inch, shadow by shadow.”

"So long," he said.

"See you tomorrow."

The meeting in the school corridor, a year and a half later, I keep reliving in

my mind, as if I were going through a series of reincarnations that end up

each time in the same failure. I saw that he recognized me, and there was

no use in my hoping that I would seem not to have recognized him,

because I could feel the expression of surprise on my face. He didn't speak.

I didn't speak. We just kept on walking.

“Han pasado cinco o diez años sin que haya vuelto a pensar en Cletus para nada y, de pronto, algo me lo recuerda… entonces lo veo acercarse hacia mí por el pasillo de aquel enorme instituto, y se me tuerce el gesto al recordar que no le dije nada. E intento quitármelo de la cabeza”

“… entonces tenía clase de matemáticas en el segundo piso, en la otra punta del edificio, y el tiempo justo para llegar antes de que sonara el timbre”

“Sabía que lo que le había ocurrido a Cletus era algo terrible y que él quedaría marcado para siempre, pero no intenté ponerme en su lugar”