This is a unique book - both in terms of the author's approach and in terms of the circumstances under which it was written. Most history books I read describe a sequence of events, possibly with some analysis as to how the events are related. In this book, however, the author devotes the first half of the book to describing Japanese beliefs (religious and otherwise), and only then goes into history. As such, the book is as much a window into the Japanese mind at that time as a history of Japan. Simultaneously, because the book was published over one hundred years ago, it is a window into the European mind at that time. Regarding the latter, there certainly were a few places where the authors perspective, viewed from today, is at best naive and at worst offensive. Be that as it may, I deeply enjoyed the book.

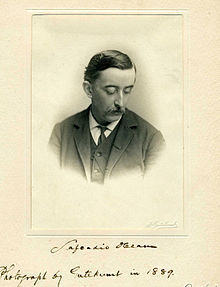

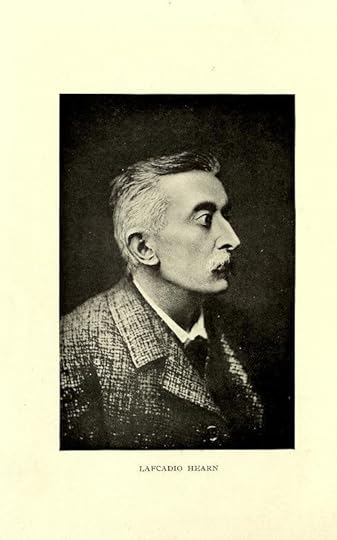

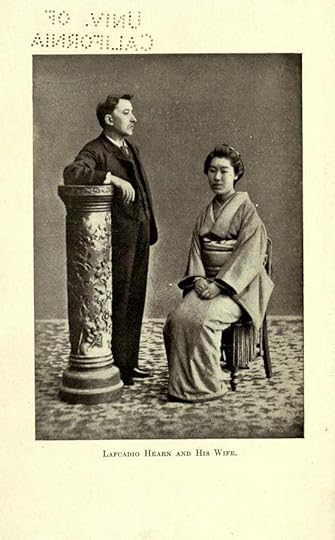

The author is Lafcadio Hearn, a European who moved to Japan in 1890 and remained there until his death in 1904. The author died between the completion of the book and its publication. Having lived in Japan for 14 years, become a naturalized Japanese citizen, and married a Japanese woman, so I think he is reasonably qualified for the task he set out to do in this book. As I said earlier, the first half of the book is a description of Japanese beliefs, most of the emphasis being on the religion of ancestor worship. I think, had I known at the outset that I would be reading a book about Japanese religion, I would not have bought the book, as I did not think that this was a subject I was interested in. However, the author began the book by insisting that in order to understand a people, you must first study their beliefs - in particular, religious beliefs - and I now agree that this statement is reasonable.

Simply put, ancestor worship firstly is the idea that your dead ancestors still exist as ghosts, and moreover, that they depend upon you for nourishment (given in the form of sacrifices). Secondly, it is the idea that ghosts are responsible for natural phenomena both good and bad, and therefore just as they depend on you, you depend on them (for a good harvest, avoiding natural disaster, etc). In other words, in ancestor worship, you have a two-way transaction between the living and the dead - the living provide the dead with nourishment, and in return, the dead protect the living against natural disasters.

This has helped me to understand why Eastern cultural fathering a son being seen as the all-important filial piety (duty to parents)? I had assumed that the motivation came from some vague notion of "continuing the proud family name". In fact, it is far more pragmatic. After you die, you will be depending on your descendants for nourishment. Moreover, "descendants" is defined in such a way that female children don't count. Therefore, should you fail to father a son, after you die you, your parents, and all your other ancestors will be completely fucked. One way to think of it is that death really just means being sent to an old folks home to you live forever together with all of your already dead ancestors. Food in this old folks home is not free - your living descendants must send food money every month. Now, imagine that you die without fathering a son. You show up at the old folks home, and now your dad and all of your other ancestor's food money that they have been enjoying is abruptly cut off, forever. Moreover, it's 100% your fault - your dad shakes his head and says "Son...what the fuck. What have you done..."? Now you have to spend eternity in this old folks home with all of your ancestors, all of whom hate you, and with no money for food. This doesn't sound that far off from the Christian concept of hell. Therefore, from the economic perspective of incentives, the main difference between ancestor worship and Christianity is the conditions under which one is condemned to an eternity in hell.

With this in mind, practices in China such as wife-kidnapping (where girls as young as 12 are kidnapped and sold to farmers in distant parts of the country as wives) and selective abortion of girls under the one-child policy, make perfect sense - they are natural responses to incentives. Or, to be more precise, it makes sense provided the dogma of ancestor worship continues to be taken literally today. As I go about my daily life in Taiwan, I see evidence of the ritual of ancestor worship everywhere - old men and woman burning paper money in little bins on the sidewalk as I walk to and from the university, tables covered with offerings of potato chips, beer, and other snacks amidst burning incense sticks arranged in front of storefronts. What is less clear is whether the people doing this are just going through the motions of ritual without really believing, much like many modern-day Christians in the west. I haven't had a chance to investigate this, but my guess is that in the big cities, this may well be the case. However, I find it highly plausible that in the remote and poorly educated countryside of China - which is where wife-kidnapping is most common - these beliefs might still be taken literally.

The actual history portion of the book was interesting in that it was written prior to either of the world wars. Towards the end, the author made some speculations as to the future tribulations of both Japan and Europe, some of which was prescient.