What do you think?

Rate this book

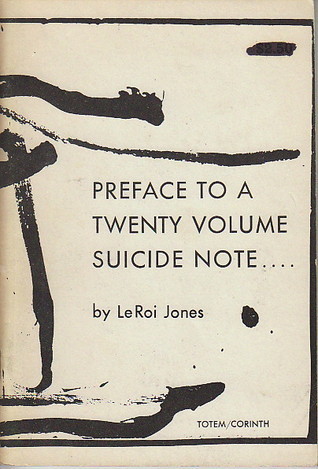

47 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1961

envious blues feeling

separation of church & state

grim calls from drunk debutantes

If they

leave their brittle selves behind (our time's

a cruel one.

Children

of winter. (I cross myself

like religion

Children

of a cruel time. (the wind

stirs the bones

& they drag clumsily

thru the cold.)

These children

are older than their words,

and cannot dance.