There is something analogous in Hume’s characters of Cleanthes, Philo, Demea, and their pursuit of natural religion to the workings of a dog track. In order to get the dogs to run in a circle, a metal, rabbit-shaped animal—often given a cute name like “Sparky”--appears in front of the pack just when the starting gate is lifted. The dogs, driven by natural instinct, catch sight of Sparky and begin the race. Sparky, driven by an intelligently designed mechanism that surpasses the speed of even the fleetest greyhound, manages to stay ahead of them until he disappears at the finish line. To the gambler, the fastest dog wins the race, but to a more dispassionate observer, the real winner is Sparky. In Hume’s Dialogues, Demea and Philo are the greyhounds, but the winner of the race is the machine, the Sparky-like Cleanthes.

That Cleanthes emerges as the winner of the debate on natural religion isn’t really a surprise. In the first chapter of the Dialogues, Pamphilus introduces Cleanthes as the accurate philosopher, Philo as the careless skeptic, and Demea as the rigidly inflexible orthodox. It is rare in a competition for anyone either careless or rigidly inflexible to prevail. These aren’t the qualities of a winner. While Philo may give the best account of himself with the depth and breadth of his knowledge, I think Cleanthes delivers the ultimate rejoinder at the conclusion of Part VII. Philo’s theories, Cleanthes posits, are “whimsies … that may puzzle but never can convince us.” Cleanthes is forever contemptuous of Philo’s skepticism. That skepticism is “fatal to knowledge but not to religion.” While I tend to identify more with Philo the skeptic or Demea the mystic, their reasoning and eloquence are ultimately futile. If your opponent in a religious debate is convinced that the Deity is “similar to human mind and intelligence” and endowed with anthropomorphic characteristics, any attempts to dislodge him from that belief are likely to end in failure.

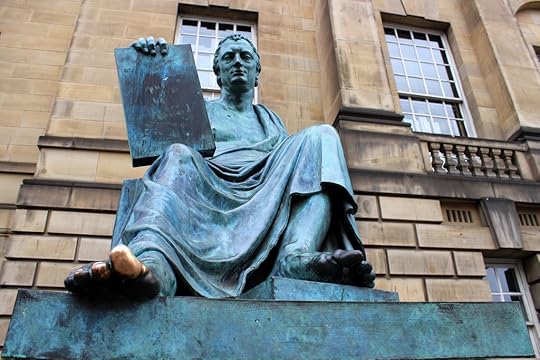

Cleanthes thesis is succinct: “the Author of Nature is somewhat similar to the mind of man, though possessed of much greater faculties.” He goes on to say “by this argument, and by this argument alone, do we prove at once the existence of a Deity and his similarities to human mind and intelligence.” The world is “nothing but a machine” of the highest order that is “subdivided into an infinite number of lesser machines.”

Philo immediately attacks this premise. How can order alone be the proof of design? Couldn’t matter itself function as the source, or what he more often calls the “spring,” of the order that we see in the world? Design is merely one of the springs or principles of the universe.

In response, Cleanthes makes one of his best points when he asks Philo to consider the human eye. If you think about the marvelous structure of the eye, isn’t it obvious that some kind of design is responsible for its function? This argument might seem less persuasive in the modern age where people carry around man-made eyes embedded in their cell phones, but even today science is better able to explain the dynamics of the distant universe than the inner workings of the human mind. Can even the smartest man explain how we see, or how we remember things from our past? Where in the plethora of animals is the dividing line between consciousness and mere instinct, and how did humans rather than chimps acquire it? Cleanthes reference to the human eye is very brief, but this portion of the dialogue is especially persuasive to the notion of intelligent design.

Cleanthes takes issue with Demea’s proposition that God is unknowable. Humans, Demea says, are too “infirm” to understand the Divine, and it is dangerous to equate God to man. Mystics like Demea, Cleanthes replies dismissively, are really nothing more than atheists. Demea later asks Cleanthes for data to support his thesis. Philo quickly agrees with Demea and states, “we have no data to establish any system of cosmogony.” Human experience is too limited to make positive assertions about natural religion. The world, Philo says, resembles the working of an animal or a vegetable; nature is spontaneous and follows its own accord without any particular design. It just grows. Cleanthes response is simple. Use your common sense, Philo. Does the world really resemble a vegetable? Philo’s arguments are pretty, but they are unconvincing. Cleanthes isn’t citing any data; he relies on what I would call his “gut feel.” To impute the nature of the world to some kind of regenerative animal or vegetable doesn’t really refute his contention—those theories might even corroborate it.

Demea then proposes two classical proofs of the existence of God. The first is the “voluntary agent or first mover” theory of Aquinas fame. Philo takes issue with this and says that motion is just a principle of matter. Nature doesn’t require a prime mover to be in motion. Cleanthes, who has little use for proofs in the first place, makes an interesting point about camels. What good are they? Would the world have dissolved if camels or any domestic animal had never existed? Cleanthes makes a strong point here, just as he did when he put forth the example of the human eye. In my opinion, the human eye and camels are good arguments for design, or what Cleanthes more accurately calls “benevolent design.” Camels are indeed natural creatures, but it is hard to understand why they exist if not for some kind of divine benevolence, or perhaps some divine sense of humor that exists in a Deity (just as it exists in man) but is totally absent from nature.

A second classical argument about the existence of God is the ontological one. There must have been a first being, Demea says, because nothing can cause itself to exist. Not so, replies Cleanthes. In a conclusion that could have emanated from Philo, Cleanthes says that the material universe itself could be the first Being. There is something contradictory about this explanation. If Cleanthes admits that the universe could be the first Being, it follows that the universe could also be the source of its own design, but he denies this. Cleanthes is not a logician like Philo. As the debate unfolds, Cleanthes relies less on logic and philosophy to support his contention of intelligent design and falls back on that age old device to support a position that cannot be proven by evidence: belief.

In the last two chapters of the Dialogues, the nature and pervasiveness of evil play central roles in the debate. Here Cleanthes is relatively silent, his rebuttals falling short of the mark. When Demea and Philo insist that most men are miserable, Cleanthes can only say that he has observed “something like what you say in others,” but rarely in himself. He is a happy man indeed. Health, he says, is more common than sickness. Pleasure is more common that pain. That might be so, agrees Philo, but isn’t pain “infinitely more violent and durable?” Philo is ready to rest his case at the end of Chapter X. Heretofore, he has resorted to metaphysical arguments to refute Cleanthes’s system of design, but now he is certain the Cleanthes cannot explain how an infinitely powerful and infinitely wise Deity can be conjoined with the violent nature of the world.

Cleanthes doesn’t have much of a counter punch. His lame contention that the world experiences lesser evil in place of a greater one lacks credibility. Seemingly tired of the discussion, he asks Philo to explain the nature of evil. He does so over several pages. Cleanthes is not impressed, and he recovers himself to make what I think is his strongest statement in support of his position

A false, absurd system, human nature, from the force of prejudice, is capable of adhering to with obstinacy and perseverance; but no system at all, in opposition to a theory supported by strong and obvious reason, by natural propensity, and by early education, I think it absolutely impossible to maintain or defend.

It is better to believe in something than in nothing. A few pages later Cleanthes says, “religion, however corrupted, is better than no religion at all.”

Is that the final word? Is a corrupted religion better than no religion at all? Philo very properly argues that few doctrines have led to more misery in the records of history than religion. He is correct, but most people still believe because most people are not philosophers or skeptics. From my own perspective, I like facts and data more than I like stories, so my personal inclination is to side with Philo, or perhaps more closely to Demea. God probably does exist, in one form or another, but he is unknowable, and any attempts to get at him eventually dissolve into nothingness. It is certainly possible that God looks exactly like the strong, grandfatherly figure that Michelangelo drew at the apex of The Sistine Chapel. But mankind’s experience with God is minimal, and our data, as Philo contends, is nonexistent. It is just as likely that God created humans experimentally in an effort to devise something totally unlike himself. God might resent any comparisons between Him and us.

At the end of Part IV in the Dialogues, before the debate has really gained any traction, Cleanthes says, “I have found a Deity; and here I stop my inquiry. Let those go farther who are wiser or more enterprising.” I might not agree with Cleanthes, but his practical arguments about the Author of Nature prevail over the skeptical and the mystical.