What do you think?

Rate this book

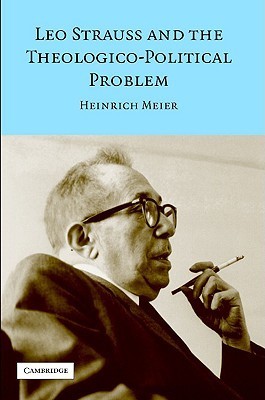

206 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2003

“What begins with the emancipation of politics from theology results ultimately, after the successful unleashing of a world of increasing purposive rationality and growing prosperity, in a state of incomprehension of and indifference towards the original sense of the theologico-political critique, a state in which the demands of politics are rejected with the same matter-of-factness as those of religion.”Whether democratic politics have deteriorated, or their unsavouriness has simply become more visible, the widespread political disillusion and ennui is apparent. This is the opening, once again, for religion to reassert its claims amid the resulting turmoil.

“Only through the Bible is philosophy, or the quest for knowledge, challenged by knowledge, viz. by knowledge revealed by the omniscient God, or by knowledge identical with the self-communication of God. No alternative is more fundamental than the alternative: human guidance or divine guidance. Tertium non datur”[there is no third way].