We’ve all read epic family sagas—sweeping multi-generational tales like The Thorn Birds, The Godfather, Roots, the Star Wars franchise, and anything remotely connected to the British Monarchy. So as I read Judith Barrow’s Howarth Family trilogy, I kept trying to slot them into those multigenerational tropes:

*First generation, we were supposed to see the young protagonist starting a new life with a clean slate, perhaps in a new country.

*The next generation(s) are all about owning their position, fully assimilated and at home in their world.

*And the last generation is both rebel and synthesis, with more similarities to the first generation made possible by the confidence of belonging from the second one.

But the complex, three-dimensional miniatures I met in the first three books of the trilogy stubbornly refused to align with those tropes. First of all, there’s Mary Howarth—the child of parents born while Queen Victoria was still on the throne—who is poised between her parents’ Victorian constraints, adjustment to a world fighting a war, and their own human failures including abuse, alcoholism, and ignorance.When Pattern of Shadows begins in 1944, war-fueled anti-German sentiment is so strong, even the King has changed the British monarchy’s last name from Germanic Saxe-Coburg to Windsor. Mary’s beloved brother Tom is imprisoned because of his conscientious objector status, leaving their father to express his humiliation in physical and emotional abuse of his wife and daughters. Her brother Patrick rages at being forced to work in the mines instead of joining the army, while Mary herself works as a nurse treating German prisoners of war in an old mill now converted to a military prison hospital.

Mary’s family and friends are all struggling to survive the bombs, the deaths, the earthshaking changes to virtually every aspect of their world. We’ve all seen the stories about the war—plucky British going about their lives in cheerful defiance of the bombs, going to theaters, sipping tea perched on the wreckage, chins up and upper lips stiff in what Churchill called “their finest hour”. That wasn’t Mary’s war.

Her war is not a crucible but a magnifying glass, both enlarging and even inflaming each character’s flaws. Before the war, the Shuttleworth brothers might have smirked and swaggered, but they probably wouldn’t have considered assaulting, shooting, raping, or murdering their neighbors. Mary and her sister Ellen would have married local men and never had American or German lovers. Tom would have stayed in the closet, Mary’s father and his generation would have continued abusing their women behind their closed doors. And Mary wouldn’t have risked everything for the doomed love of Peter Schormann, an enemy doctor.

I was stunned by the level of historical research that went into every detail of these books. Windows aren’t just blacked out during the Blitz, for example. Instead, they are “criss crossed with sticky tape, giving the terraced houses a wounded appearance.” We’re given a detailed picture of a vanished world, where toilets are outside, houses are tiny, and privacy is a luxury.

The Granville Mill becomes a symbol of these dark changes. Once a cotton mill providing jobs and products, it’s now a prison camp that takes on a menacing identity of its own. Over the next two volumes of Howarth family’s story, it’s the mill that continues to represent the threats, hatred, and violence the war left behind.

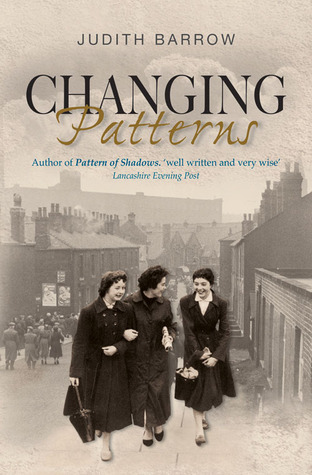

Unlike the joyful scenes we’re used to, marking the end of the war and everyone’s return to prosperity and happiness, the war described in these books has a devastatingly long tail. When Changing Patterns takes up the story in 1950, Mary and Peter have been reunited and are living in Wales, along with her brother Tom.

But real life doesn’t include very many happy-ever-afters, and the Howarths have to live with the aftermath of the secrets each of them has kept. The weight of those secrets is revealed in their effect on the next generation, the children of the Howarth siblings. The battle between those secrets and their family bonds is a desperate one, because the life of a child hangs in the balance.

Finally, the saga seems to slide into those generational tropes in Living in the Shadows, the final book of the Howarth trilogy. Interestingly enough, this new generation does represent a blend of their preceding generations’ faults and strengths, but with the conviction of their modern identities. Where their parents’ generation had to hide their secrets, this new generation confidently faces their world: as gay, as handicapped, as unwed parents, and—ultimately shrugging off their parents’ sins—as family.

But I didn’t really understand all of that until I considered the title of the prequel (released after the trilogy). 100 Tiny Threads tells the story of that first generation, their demons, their loves, their hopes, and their failures, and most importantly, their strength to forge a life despite those failures. That book, along with the novella-sized group of short stories in Secrets, gives the final clues to understanding the trilogy. As Simone Signoret said, “Chains do not hold a marriage together. It is threads, hundreds of tiny threads, which sew people together through the years.” And it’s both those secrets and those threads not only unite them into a family, but ultimately provide their strength.

This is the part where I’m supposed to tell you that each of these wonderful books can be read alone. But no, don’t do that. In fact, if you haven’t read any of them, you’re luckier than I am, because you can start with the prequel and read in chronological order. I chose to review these books as a set, and I believe that’s how they should be read.

Every now and then, I come across books so beautifully written that their characters follow me around, demanding I understand their lives, their mistakes, their loves, and in this case, their families. Taken together, the Howarth Family stories are an achievement worth every one of the five stars I’d give them.