What do you think?

Rate this book

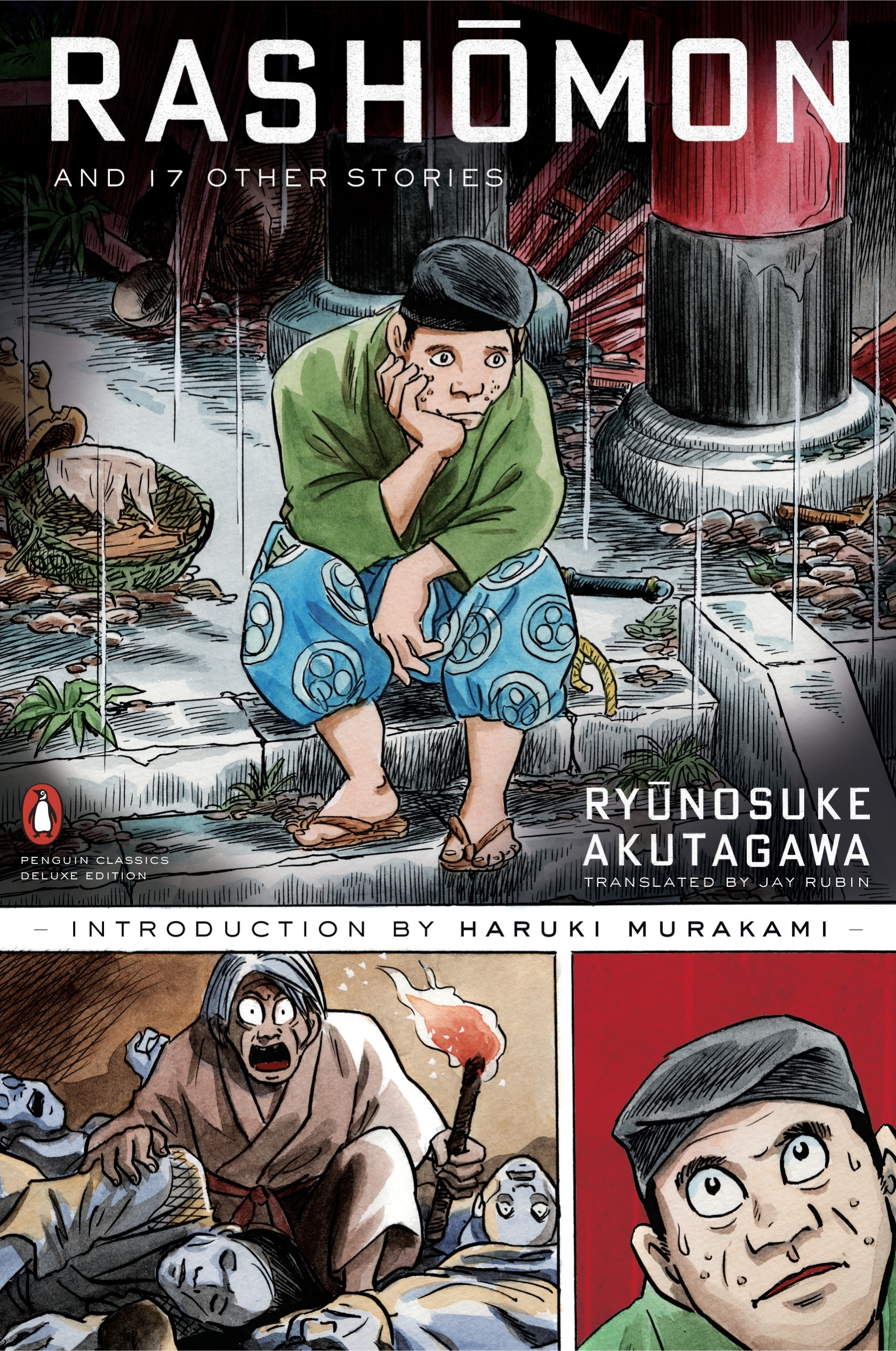

268 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1927

Early this mornin', when you knocked upon my door

Early this mornin', ooh, when you knocked upon my door

And I said, "Hello, Satan, I believe it's time to go"

Me and the devil, was walkin' side by side

Me and the devil, ooh, was walkin' side by side

-Me and the Devil Blues-

Robert Johnson