What do you think?

Rate this book

224 pages, Hardcover

First published November 1, 1989

- Some shells develop protective coloration (e.g., spots, stripes, etc) as a defense primarily against vertebrate predators (i.e., fish), as most invertebrates hunt by smell rather than sight. Some shells such as the surface-floating "bubble shells" even evolved "protective shading" so that they are dark blue/purple on top and lighter on the bottom, so that when viewed from above they blend with the ocean, and when viewed from below they blend with the sky, (much like some WWI aircraft camouflage).

- And speaking of predators, mollusks include the same wide range of eating styles as do vertebrates — some are pastoral "vegetarians" (feeding on algae or sifting silt), while others are SERIOUS predators, quickly or (often) very slowly killing and devouring their prey. There are even "vampire snails" that attach themselves to sleeping sharks or rays and feed on their blood. Relatedly and also like mammals, most predator shells are loners, while "grazing" shells such as olives can live in large herd-like colonies.

- And speaking of feeding, many "tinted" shells get their color from what they eat; e.g., a shell that lives on pink coral may ultimately built that color into its growing shell, etc.

- Many shells with fancy knobs, leaves and spines grow in spurts of rapid shell growth followed by a pause to add a row defensive "varices;" these generally occur in fixed increments of either 180° (resulting in a "maple leaf" design), or 60° which results in the common "caltrop" configuration, (see murex photo way below).

- Cephalopods (octopus, squid, cuttlefish) have "de-evolved shells" from their nautiloid and ammonoid ancestors into (A) those internal "cuttlefish bones" placed in birdcages for beak-sharpening; (B) those clear, blade-like strips you find when eating squid (at least when the whole animal is prepared as in Asia, vs. Western-style squid rings); and (C)...well, nothing in octopuses, where they have disappeared altogether.

- And speaking of nautiloids, the "paper nautilus" is neither a proper nautilus nor even shell at all — it's actually an egg case that evolved separately into that classic Fibonacci spiral form, and so is a perfect example of evolutionary convergence and a "testament to the functional constraints of environment on form."

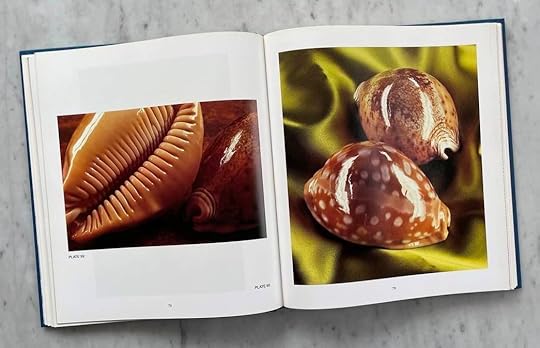

- Those smooth and glassy cowrie and olive shells are in the evolutionary process of reducing or internalizing their shells, and may in some distant future once again become totally shell-less, going the way of those beautiful ocean nudibranchs (ooh, ahh) or their gross terrestrial counterparts, slugs (yuck; see cool quote at the end of the review**).

(Cowrie shell on it's SLLOOOOWWW journey to becoming just a snail—again…)

- I've long been kinda fascinated by taxonomy — basically, scientific naming — and in this area, seashells do NOT disappoint: we have here the Knobbed Whelk, Spiral Babylon, Miller's Nutmeg, the whole Wentletrap family (Noble, Precious and Magnificent), Lazarus Jewel Box, Pacific Lion's Paw (which frankly looks like every other scallop to me; see book jacket photo), and — my favorite — the Exalted Nut Clam.

- And speaking of™ taxonomy, accurate taxonimic classification remains very much an evolving science, especially as we better understand genetics. Shells that were previously grouped together based on appearance are now being reevaluated and reclassified based on genetic rather than visual characteristics. Science!

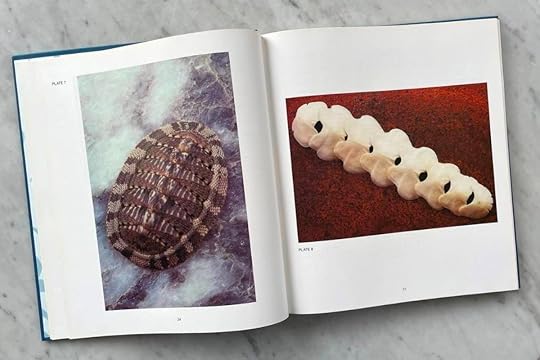

- The Squamose—aka "Snakeskin"—Chiton (left)…is that just the coolest thing or what?

(Can Google these for even clearer images of their remarkably snakeskin-like mantles)

- I never understood before the function of the "siphon channels" that run along the aperture of most gastropods, but I now know that there are distinct "inhalent" and "exhalent" channels that serve as the "mouths" and "butts" of such shells. Cool and gross!

- The book mentioned a few "perverse" shells, which got me curious as to just what the hell that "-verse" suffix means. Turns out, it just means "turn," so we get OBVERSE (“turn toward”), REVERSE (“turn back”), CONVERSE (“turn with”), INVERSE (“turn inside out”), UNIVERSE (“turned into one”), DIVERSE (“turn separately”), AVERSE (“turn away”), SUBVERT ("turn from below") and finally PERVERSE (“turn the wrong way”). Also learned some new, shell-specific vocab here, such as periostracum and byssus.

- And yes, while gastropods are the true stars here, bivalves also get their due, proving that at least some of them are beautiful, (or can at least be beautifully photographed):

(That was actually one of my delicious murexes. Like most shells, these are surprisingly hard to spot underwater as they are TOTALLY encrusted with algae, coral and other crud, and they take FOREVER to clean. That's also why most dive clubs try to get at least one dentist or dental assistant as a member, because no tools are better for cleaning shells than old dental picks!)Also—never quite understand why, but certain locations were known hotspots for particular shells. Off the southern coast was a formation we called Conch Rock, because whenever you dove there you would invariably find 1-2 giant spider conches (also edible), as well as the occasional scorpion conch; and then up north off another chunk of shore you'd invariably find murexes and eggshell cowries. Water temperature, wave action, sand vs. coral base…not sure what it was, but it was like driving through different neighborhoods.