What do you think?

Rate this book

164 pages, Paperback

Published July 1, 2016

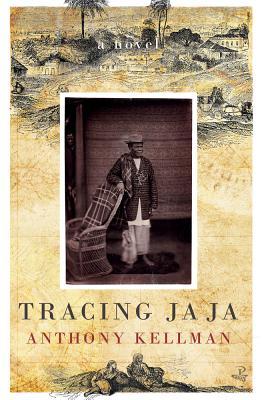

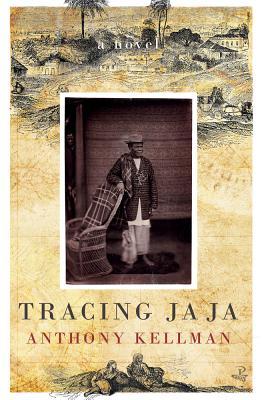

It is a passionate work of historical fiction drawing on actual events, to uncover one of the many atrocities of British colonial history. The novel engages the reader on both the emotional and cerebral level. We admired, and were moved by, Kellman’s portrayal of Jubo Jubogha, the African King, his resilience and refusal to submit to the indignities imposed on him by his British colonial jailers.

Much of the strength of Kellman’s work lies in his lyrical evocation of place, especially the Caribbean landscape. His portrayal of the people of Barbados captures both their pride in their African past and the suffering they endured. Tracing JaJa is a remarkable novel about human endurance, our capacity to find beauty and love even in the darkest of circumstances.

Peepal Tree aims to bring you the very best of international writing from the Caribbean, its diasporas and the UK. Our goal is always to publish books that make a difference, and though we always want to achieve the best possible sales, we're most concerned with whether a book will still be alive in the future.