The Old Curiosity Club discussion

The Haunted Man

>

The Haunted Man - Part One

If you don't have a copy of The Haunted Man, you can read it online or download in Kindle, epub (Nook), or other formats here:

http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/644

Another ebook version is here:

https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/d/dick...

http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/644

Another ebook version is here:

https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/d/dick...

"Everybody may sometimes be right; “but THAT’S no rule,” as the ghost of Giles Scroggins says in the ballad."

The ballad: (click on page 2 at the bottom for the rest of the ballad)

http://levysheetmusic.mse.jhu.edu/col...

The ballad: (click on page 2 at the bottom for the rest of the ballad)

http://levysheetmusic.mse.jhu.edu/col...

Hi Peter and Curiosities,

Hi Peter and Curiosities,Glad to be joining a Dickens Christmas read, despite its dark beginning! I enjoyed the paragraph repetitions, until 'When', when I lost track of the context and was glad to finally return to our protagonist. Very atmospheric.

Swidger is a great name. It took me a while to realize Redlaw (another interesting choice) calls the couple by the man's first name, William, as does the narrator. I was also confused by Redlaw asking what William was going to tell him about his 'wife's honour.' Had he already begun to tell him? Missed that part.

The poor young gentleman, alone at school for the holidays, reminds me of Scrooge -- wasn't that part of his past? Then we learn that Redlaw had a similar childhood, with the exception of his sister and a friend. Intriguing that he considers helping this student, but instead takes the ghost's offer to forget his own past. Not very wise, for such a learned professor.

Everyman wrote: "If you don't have a copy of The Haunted Man, you can read it online or download in Kindle, epub (Nook), or other formats here:

Everyman wrote: "If you don't have a copy of The Haunted Man, you can read it online or download in Kindle, epub (Nook), or other formats here:http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/644

Another ebook version is here:

h..."

The Delphi Classics edition, which doesn't have the lettering problems that some of the books at Gutenberg have, is for one dollar at Barnes & Noble. I do support Gutenberg as a great resource, though, too.

Vanessa wrote: "Hi Peter and Curiosities,

Glad to be joining a Dickens Christmas read, despite its dark beginning! I enjoyed the paragraph repetitions, until 'When', when I lost track of the context and was glad ..."

Hi Vanessa

Glad you are aboard for this read.

I think the calling of a person by two different names is a key hint to this story. The William/Swidger combination represents two parts of one person. Later in this part we have the spectre manifest itself and assume the role of the very dark side of Redlaw. Not to give any spoilers away, but we do see at the end of Part One how Redlaw’s curse will be to separate a person from their former self through the loss of memory. Thus, each person will have two parts to them, a part that can function and exist in society and a second part that has lost, buried or forgotten a part of their existence. Very Jeckyl and Hyde in some ways.

Here is a link to an article that explains the concept. Jung wrote after Dickens, of course, but I think Dickens was ahead of his time.

https://academyofideas.com/2015/12/ca...

Glad to be joining a Dickens Christmas read, despite its dark beginning! I enjoyed the paragraph repetitions, until 'When', when I lost track of the context and was glad ..."

Hi Vanessa

Glad you are aboard for this read.

I think the calling of a person by two different names is a key hint to this story. The William/Swidger combination represents two parts of one person. Later in this part we have the spectre manifest itself and assume the role of the very dark side of Redlaw. Not to give any spoilers away, but we do see at the end of Part One how Redlaw’s curse will be to separate a person from their former self through the loss of memory. Thus, each person will have two parts to them, a part that can function and exist in society and a second part that has lost, buried or forgotten a part of their existence. Very Jeckyl and Hyde in some ways.

Here is a link to an article that explains the concept. Jung wrote after Dickens, of course, but I think Dickens was ahead of his time.

https://academyofideas.com/2015/12/ca...

Thanks, Peter, for the intro! Just to make sure I have the rules right, I'm posting under the assumption that it's ok to talk about anything in Part One, The Gift Bestowed, but nothing after that. (Not that I've read any further.)

Thanks, Peter, for the intro! Just to make sure I have the rules right, I'm posting under the assumption that it's ok to talk about anything in Part One, The Gift Bestowed, but nothing after that. (Not that I've read any further.)What struck me about "Everybody said so" is that it's pretty close to the same opening as Austen's Pride and Prejudice: "It is a truth universally acknowledged..." Does anyone know if Dickens read this? Whether he did or not, it seems to me to say a lot about both authors that Austen is so distanced and indirect in her opening words (passive verb, no clear sense at the start of what the "it" truth is), while Dickens goes straight for the punch. He can be plenty indirect himself, but that's not how he starts things here.

Like Vanessa, I was glad to be through the Whens. This surprised me a bit, because Dickens does the same kind of thing in some of my favorite openings of his other books--the Fog section in Bleak House, for instance, and a little bit at the start of Tale of Two Cities as well. But I got the feeling he was just phoning it in this time: the word "When" doesn't pack the same symbolic importance, say, as the word "Fog," and it all went on for a very long time. My first thought was that he was in a hurry and made himself a note to the effect of "insert anaphoric scene-setting here" because he already knew this would work and he had a deadline to meet, but then I checked the dates and realized Haunted Man was written before the other books. So now I'm thinking maybe this was a technique he was teaching himself--that he might not have down perfectly yet, but that would pay off beautifully later on.

I love the ghost. It's so very creepy--taking the form of increasing darkness first, then of Redlaw himself, and then he starts chanting his offer: ooooooh all three of these moves gave me chills. I went and read them to my 7 year old. Hope they don't leave him with nightmares.

Finally, I've made my students read Dickens serially lots, and I've examined how he breaks his installments up, but I don't think I've ever read one of his books serially myself, and found it agonizing to cut off with this one and make myself wait until next week. But I look forward to going back!

Hi Julie

Yes. When we read we assume that the only knowledge of the text we have is what we have read. Very hard sometimes. In a longer novel, if we are well into the book, we might project where symbolism or foreshadowing seem to be leading.

I do not know if Dickens read Austen. My guess would be that he only had a passing knowledge of her work.

From Dickens’s early work to his mature work one can definitely see his style evolve. I enjoy and agree with your observations and comments about the stylistic devices you mentioned.

I hope your daughter did not have an uncomfortable sleep, but thank you for introducing her to Dickens so early.

When we begin our reading in the new year I hope you enjoy our method of reading. I also hope you enjoy the remainder of The Ghost’s Bargain.

Yes. When we read we assume that the only knowledge of the text we have is what we have read. Very hard sometimes. In a longer novel, if we are well into the book, we might project where symbolism or foreshadowing seem to be leading.

I do not know if Dickens read Austen. My guess would be that he only had a passing knowledge of her work.

From Dickens’s early work to his mature work one can definitely see his style evolve. I enjoy and agree with your observations and comments about the stylistic devices you mentioned.

I hope your daughter did not have an uncomfortable sleep, but thank you for introducing her to Dickens so early.

When we begin our reading in the new year I hope you enjoy our method of reading. I also hope you enjoy the remainder of The Ghost’s Bargain.

Peter wrote: "Hi Julie

Peter wrote: "Hi JulieYes. When we read we assume that the only knowledge of the text we have is what we have read. Very hard sometimes. In a longer novel, if we are well into the book, we might project where ..."

Oh, I'm absolutely enjoying reading it part by part. It was difficult to stop, but also fun to be sharing the story with people in pieces. And I think I'll appreciate the craft that goes into shaping each piece more this way.

Hello everyone,

I think the beginning of The Haunted Man mirrors the beginning of the previous Christmas novel, The Cricket on the Hearth, which runs:

In both instances, we are thrown right into the action by being made to focus on one particular detail. This is very effective writing, and I hope that the rest of this Christmas tale will keep up the standards set by the first sentence, all the more so since Cricket soon began to fail for me.

In the case of The Haunted Man the immediate beginning gives us an idea of the lingering, all-pervading presence of the sinister ghost, who has cast his shadow over every detail of Redlaw's life, his outward appearance, his behaviour as well as his surroundings.

There are, as Peter said and some of you pointed out, several indirect references to Dickens's first, and most famous, Christmas ghost story, but this time it strikes me that the ghostly appearance is anything but benevolent and helpful. It seems to be a sinister personification of something that went wrong in Redlaw's life and that has bruised his soul. The similarity between the ghost and the haunted man seems to imply that, maybe, the ghost is not so much an exterior manifestation but rather an element of Redlaw's very soul. Unlike the ghosts that haunt Scrooge, Redlaw's ghost is not so much bent on making him remember things from his past, re-evaluate them and help him to become a better person, but quite on the contrary, to make him forget his past and suppress his feelings.

We see that there is a potential of sympathy within him when he wants to help the poor lonesome student, but as soon as he has concluded his mysterious bargain with the ghost, he seems to be bereft of any human feeling, which can be seen in his treatment of the little boy.

This is, all in all, a very haunting story.

I think the beginning of The Haunted Man mirrors the beginning of the previous Christmas novel, The Cricket on the Hearth, which runs:

The kettle began it! Don’t tell me what Mrs. Peerybingle said. I know better. Mrs. Peerybingle may leave it on record to the end of time that she couldn’t say which of them began it; but, I say the kettle did. I ought to know, I hope! The kettle began it, full five minutes by the little waxy-faced Dutch clock in the corner, before the Cricket uttered a chirp.

In both instances, we are thrown right into the action by being made to focus on one particular detail. This is very effective writing, and I hope that the rest of this Christmas tale will keep up the standards set by the first sentence, all the more so since Cricket soon began to fail for me.

In the case of The Haunted Man the immediate beginning gives us an idea of the lingering, all-pervading presence of the sinister ghost, who has cast his shadow over every detail of Redlaw's life, his outward appearance, his behaviour as well as his surroundings.

There are, as Peter said and some of you pointed out, several indirect references to Dickens's first, and most famous, Christmas ghost story, but this time it strikes me that the ghostly appearance is anything but benevolent and helpful. It seems to be a sinister personification of something that went wrong in Redlaw's life and that has bruised his soul. The similarity between the ghost and the haunted man seems to imply that, maybe, the ghost is not so much an exterior manifestation but rather an element of Redlaw's very soul. Unlike the ghosts that haunt Scrooge, Redlaw's ghost is not so much bent on making him remember things from his past, re-evaluate them and help him to become a better person, but quite on the contrary, to make him forget his past and suppress his feelings.

We see that there is a potential of sympathy within him when he wants to help the poor lonesome student, but as soon as he has concluded his mysterious bargain with the ghost, he seems to be bereft of any human feeling, which can be seen in his treatment of the little boy.

This is, all in all, a very haunting story.

However, there are also some elements I strongly dislike: There is the rambling old man and his constant question, "Where is my son William?", and there is also a certain lengthiness in the whole Swidger episode. Mr Swidger, for instance, is some kind of Columbo, only less astute, in that he is given to a lot of pointless talk - and this stretches out the first chapter more than it would have been necessary for me.

Okay, the first one of you to call me a grump will be treated to a mug of negus in the Travellers' Twopenny!

Okay, the first one of you to call me a grump will be treated to a mug of negus in the Travellers' Twopenny!

Tristram wrote: "Okay, the first one of you to call me a grump will be treated to a mug of negus in the Travellers' Twopenny!.."

Grump.

Grump.

Tristram wrote: "Hello everyone,

I think the beginning of The Haunted Man mirrors the beginning of the previous Christmas novel, The Cricket on the Hearth, which runs:

The kettle began it! Don’t tell me what Mrs...."

Tristram

I agree with you completely when you comment that this ghost is “a sinister ghost” and he does cast a shadow over every detail of Redlaw’s life. The mood and feeling of the opening part of The Haunted Man does have a much more “unpleasant tone and mood” as you note than in A Christmas Carol. Marley’s ghost is much less jagged and heavy. In a span of just a few years Dickens has certainly changed his methodology of Christmas stories.

Your comment that the ghost that haunts Redlaw is “an element of Radlaw’s own very soul” is, to my mind, exactly what Dickens wanted to suggest. In my message 6, I give a reference to an article on Jung’s concept of the shadow. There I go with more Jung. It seems that I’m in Jung mode lately.

I do see the Ghost in The Haunted Man as radiating from within Radlaw as opposed to being external like Marley appears to be in A Christmas Carol. This is a major development in how Dickens crafts, develops, and motivates his characters. While we should keep a Christmas focus to our comments, A Haunted Man roughly parallels D&S which also seems to be the turning point where Dickens also presents his characters with much more psychological depth.

I think the beginning of The Haunted Man mirrors the beginning of the previous Christmas novel, The Cricket on the Hearth, which runs:

The kettle began it! Don’t tell me what Mrs...."

Tristram

I agree with you completely when you comment that this ghost is “a sinister ghost” and he does cast a shadow over every detail of Redlaw’s life. The mood and feeling of the opening part of The Haunted Man does have a much more “unpleasant tone and mood” as you note than in A Christmas Carol. Marley’s ghost is much less jagged and heavy. In a span of just a few years Dickens has certainly changed his methodology of Christmas stories.

Your comment that the ghost that haunts Redlaw is “an element of Radlaw’s own very soul” is, to my mind, exactly what Dickens wanted to suggest. In my message 6, I give a reference to an article on Jung’s concept of the shadow. There I go with more Jung. It seems that I’m in Jung mode lately.

I do see the Ghost in The Haunted Man as radiating from within Radlaw as opposed to being external like Marley appears to be in A Christmas Carol. This is a major development in how Dickens crafts, develops, and motivates his characters. While we should keep a Christmas focus to our comments, A Haunted Man roughly parallels D&S which also seems to be the turning point where Dickens also presents his characters with much more psychological depth.

I like how Redlaw’s inner chamber is part library and part laboratory. It reminds me of the setup in Sherlock Holmes’ living quarters.

I like how Redlaw’s inner chamber is part library and part laboratory. It reminds me of the setup in Sherlock Holmes’ living quarters.

Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Okay, the first one of you to call me a grump will be treated to a mug of negus in the Travellers' Twopenny!.."

Grump."

I didn't expect you to be the first one to call me grump, Everyman! Does that not re-open the question of Cricket as to whether it was the pot or the kettle who started it?

Grump."

I didn't expect you to be the first one to call me grump, Everyman! Does that not re-open the question of Cricket as to whether it was the pot or the kettle who started it?

Peter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Hello everyone,

I think the beginning of The Haunted Man mirrors the beginning of the previous Christmas novel, The Cricket on the Hearth, which runs:

The kettle began it! Don’t ..."

It is quite interesting in this context that Scrooge addresses the question whether Marley is really a ghost or a figment of his imagination brought about by a morsel of incompletely digested food. You know, the famous quotation as to whether Marley has more of gravey than the grave about him. Redlaw does not seem to raise that question at all although he is a scientist. But then maybe he has been under the spell of the ghost's hauntings for so long a time that he takes the ghost for granted.

I think the beginning of The Haunted Man mirrors the beginning of the previous Christmas novel, The Cricket on the Hearth, which runs:

The kettle began it! Don’t ..."

It is quite interesting in this context that Scrooge addresses the question whether Marley is really a ghost or a figment of his imagination brought about by a morsel of incompletely digested food. You know, the famous quotation as to whether Marley has more of gravey than the grave about him. Redlaw does not seem to raise that question at all although he is a scientist. But then maybe he has been under the spell of the ghost's hauntings for so long a time that he takes the ghost for granted.

Yes. I think Stephen and Tristram are correct. The point about Redlaw being a scientist, scholar, and living in the surroundings of a library and a laboratory do clearly point to a character who would probably have a more inquisitive and analytical mind. Yet, as Tristram noted, it seems that he has been haunted before and accepts the situation.

There is no humour in Redlaw’s encounters with the Spectre, or his night’s activities. Gloom and darkness pervade. Dickens has become a more somber writer, even at Christmas.

There is no humour in Redlaw’s encounters with the Spectre, or his night’s activities. Gloom and darkness pervade. Dickens has become a more somber writer, even at Christmas.

Well, now, I just realized I've been reading the Haunted House and not the Haunted Man. But now the ghost has tugged me in and I cannot leave until the end. So carry on, I'll join you all in January. But if you ever read the Haunted House, I'll be ready. Taking notes just in case.

Well, now, I just realized I've been reading the Haunted House and not the Haunted Man. But now the ghost has tugged me in and I cannot leave until the end. So carry on, I'll join you all in January. But if you ever read the Haunted House, I'll be ready. Taking notes just in case.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Well, now, I just realized I've been reading the Haunted House and not the Haunted Man. But now the ghost has tugged me in and I cannot leave until the end. So carry on, I'll join you all in Januar..."

Xan

Always a good idea to take notes. See you in January.

Xan

Always a good idea to take notes. See you in January.

After reading the above commentaries, I reread chapter one.

After reading the above commentaries, I reread chapter one.The repetition of certain words and phrases is interesting perhaps more to an accountant than to literature majors.

Seven times Who.

Two times His dwelling.

32 times When.

Six times eighty-seven.

The duplication of His dwelling points you toward a greater concentration on that if said only once.

Seven times Who is asked and is the answer seven times has Redlaw seen the ghost?

When represents times in Redlaw's life sorrow, wrong, and trouble have been known to him.

And, six times eighty-seven, 522 in numbers are the times old Philip has said keep his memory green in all his years.

Just an observation.

Glad to be joining in on this Christmas read with everyone!

Glad to be joining in on this Christmas read with everyone!I liked the short statement as the opening line as I immediately wondered "everybody said so" in reference to what? There was a mystery before the story had barely began.

As to the "who's" and "whens", I initially appreciated the repetition as it reminded me of all the "fog" at the beginning of Bleak House. However, I soon tired of the whens, felt a bit lost and was glad to get to the meat of the story already. Although during the meat of the story, I then found myself lost as to how many people were in the room since I was confused by the Williams and Swidgers. :) I thought they were one in the same, but was glad to get clarification in these threads.

OK, so finally the ghost enters, and he is indeed sinister. I can find no good in him and it seems he wants Redlaw to forget all past sorrows, but I wonder to what end? My immediate thought was that if Redlaw has no memory of any sadness, suffering, or sorrows, then what is to become of the student he declared that he would help? I foresee Redlaw will no longer sense any urgency to help this poor sickly man because how can one have any empathy for another without having the experience or memories of suffering? I'm curious to see if I'm on the right track here as to where the story is headed.

Stephen wrote: "I like how Redlaw’s inner chamber is part library and part laboratory. It reminds me of the setup in Sherlock Holmes’ living quarters."

Stephen wrote: "I like how Redlaw’s inner chamber is part library and part laboratory. It reminds me of the setup in Sherlock Holmes’ living quarters."I liked this as well, Stephen! Then I realized that since I always lug books to work and leave them on my shelves and desk, I sort of have the same set up. Though not as cozy, I imagine, and I need to lug in a lot more books.

It's interesting that nobody seems to think it's a good move for Redlaw to take the ghost up on the deal, not even my seven year old. I guess, well, the ghost is so disturbing that it would be difficult to believe he had anything good to offer. But is "would it be a good idea to forget your bad memories?" as easy a "no" answer as it seems to be here?

It's interesting that nobody seems to think it's a good move for Redlaw to take the ghost up on the deal, not even my seven year old. I guess, well, the ghost is so disturbing that it would be difficult to believe he had anything good to offer. But is "would it be a good idea to forget your bad memories?" as easy a "no" answer as it seems to be here? There's a kind of fake suspense started in this section. The question seems to be, would this be a good idea, but we've been given the answer from the start (not if a super-sinister ghost offers it to you), so I guess the real question in this book is, why not?

Tristram wrote: " Scrooge addresses the question whether Marley is really a ghost or a figment of his imagination brought about by a morsel of incompletely digested food."

Tristram wrote: " Scrooge addresses the question whether Marley is really a ghost or a figment of his imagination brought about by a morsel of incompletely digested food."Oh yes, it's one of my husband's favorite things to randomly say around this time of year! He usually just quotes the first sentence...

“You may be an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of underdone potato. There's more of gravy than of grave about you, whatever you are!”

Gilbert wrote: "After reading the above commentaries, I reread chapter one.

The repetition of certain words and phrases is interesting perhaps more to an accountant than to literature majors.

Seven times Who.

Two ..."

Hi Gilbert

Thank you for your accounting and observations. It is a great advantage to have the Curiosities bring various and sundry skills and backgrounds to a book. I enjoy doing a close reading of a text, and while I have no mathematics skill whatsoever, I find the numbers you provide both interesting and insightful.

The repetition of certain words and phrases is interesting perhaps more to an accountant than to literature majors.

Seven times Who.

Two ..."

Hi Gilbert

Thank you for your accounting and observations. It is a great advantage to have the Curiosities bring various and sundry skills and backgrounds to a book. I enjoy doing a close reading of a text, and while I have no mathematics skill whatsoever, I find the numbers you provide both interesting and insightful.

Linda wrote: "Glad to be joining in on this Christmas read with everyone!

I liked the short statement as the opening line as I immediately wondered "everybody said so" in reference to what? There was a mystery ..."

Hi Linda

You ask important questions that arise from the reading of Part One. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if they are, in fact, the key focus of our Christmas story.

We have started to unpack our Christmas decorations today and a couple of them are looking rather old and a bit battered. They are our oldest decorations and come with the most memories. I cannot conceive how a person could exist without memories, even those that are triggered by a scruffy, but to us, priceless part of our past. Our Christmas decorations.

Your comments fit perfectly with today’s activity in our apartment.

I liked the short statement as the opening line as I immediately wondered "everybody said so" in reference to what? There was a mystery ..."

Hi Linda

You ask important questions that arise from the reading of Part One. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if they are, in fact, the key focus of our Christmas story.

We have started to unpack our Christmas decorations today and a couple of them are looking rather old and a bit battered. They are our oldest decorations and come with the most memories. I cannot conceive how a person could exist without memories, even those that are triggered by a scruffy, but to us, priceless part of our past. Our Christmas decorations.

Your comments fit perfectly with today’s activity in our apartment.

Gilbert wrote: "After reading the above commentaries, I reread chapter one.

The repetition of certain words and phrases is interesting perhaps more to an accountant than to literature majors.

Seven times Who.

Two ..."

Wow, it's good I stopped reading that after the first few lines, my headache was starting. Math, numbers, putting little dots in the middle of numbers but having to move them later, 1/2, 1/3, 2/5, whatever, anything resembling math and numbers, no thanks. :-)

The repetition of certain words and phrases is interesting perhaps more to an accountant than to literature majors.

Seven times Who.

Two ..."

Wow, it's good I stopped reading that after the first few lines, my headache was starting. Math, numbers, putting little dots in the middle of numbers but having to move them later, 1/2, 1/3, 2/5, whatever, anything resembling math and numbers, no thanks. :-)

Tristram wrote: "Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Okay, the first one of you to call me a grump will be treated to a mug of negus in the Travellers' Twopenny!.."

Grump."

I didn't expect you to be the first one t..."

He cheated. He waited until he knew I'd be asleep, then pounced. Grump.

Grump."

I didn't expect you to be the first one t..."

He cheated. He waited until he knew I'd be asleep, then pounced. Grump.

My thoughts were about Mrs. William and her strange behavior. Decorating with holly, that is. Holly leaves are not soft, they are not a joy to hold, they are jaggy and they hurt, so why would you go to the trouble of decorating each room with holly only one day before Christmas? Evergreen branches would have been easier, or candles.

A word (lots of words) on the illustrations:

Ruth Glancy in "Dickens at Work on The Haunted Man" expresses the notion that the Christmas Books offered Dickens the rare opportunity "to correct an entire work before it went to press, a luxury not permitted by the serial publication of the novels". In fact, in terms of instructing his artists regarding their illustrations, he had no such luxury at all. Working with Hablot Knight Browne on the Martin Chuzzlewit plates was comparatively simple. In October, 1843, while starting A Christmas Carol, Dickens was writing the November installment, part eleven (Chapters 27, 28, and 29).

The routine during the composition and publication of Chuzzlewit in numbers was similar to that established for the previous monthly serials. The first half of each month was devoted to writing the new installments, the second half to correcting proofs. Subjects for the plates were supplied [to Phiz] as early as possible, usually by the tenth . . . . (Patten 132)

He would furnish Phiz with a clean set of proofs and a list of suggestions for illustration. Phiz would produce sketches which Dickens could then critique; thus, month in and month out, Dickens controlled an orderly program of writing and illustration. Whatever subjects he and Phiz decided upon for the plates was immaterial, since the illustrations occupied whole pages and were included at the end of each part; the reader could locate their realized moments in the accompanying text and, if he or she so desired, have the plates bound in at those points once all nineteen numbers had been acquired.

Now, consider the plates for any of The Christmas Books after A Christmas Carol: Dickens had to direct a team of artists to produce illustrations to be dropped into specific spots in the printed text. The Pilgrim Edition of the Letters of Charles Dickens, Volume V (1847-1849), reveal how tight his creative timeline was. In under two months, Dickens completed the physical act of writing The Haunted Man, beginning on October 5th at Devonshire Terrace, London, and finishing on the night of 30 November, at the Bedford Hotel, Brighton. By November 15th, little more than a month before publication, he had the proofs for the first part, including Tenniel's frontispiece and title-page, but not including Stone's "Milly and the Old Man," to which Dickens did not respond until November 23rd. The day before, Dickens wrote to his point man, John Leech, "With a Stick" (underlined) because he was still not in possession of Leech's illustration of the Tetterby family, which would have to be dropped into the text early in part two. On November 27th, writing Stone from Brighton, Dickens had no proofs for the artist, and had to describe what he had just written ("Sir, there is a subject I have written today for the third part, that I think and hope will just suit you."). By December 1st, Leech was still not in possession of the corrected proofs for the third part, and Dickens, fearing Leech's other work was slowing him down, diplomatically asked him to pass the last illustration, the dinner in the great hall, over to Stanfield (who, though not much of a caricaturist, would handle well the architectural elements of the scene). And yet, by December 13th, Dickens was able to send Mrs. Richard Watson an advance copy, even though Forster probably did not turn over the final proofs corrected until about a week previous. Having no rush proofs for part four, Dickens elected to go twenty-nine pages without a single illustration.

An added complication was that Dickens was supplying Mark Lemon with proofs to facilitate the staging of The Haunted Man, but certainly this break-neck schedule was worse than the measured routine Dickens followed in getting out a monthly serial installment.

I find that very interesting. What I don't understand is why he used so many illustrators for THM. It seems to me all the stuff talked about before this could have been made easier if he was only dealing with one artist. If anyone knows why he used four different artists for one small book, please let me know. Oh, perhaps it would less confusing for us if I listed the four illustrators. They were John Tenniel, John Leech, Clarkson Stanfield, and Frank Stone.

Whereas A Christmas Carol, more modestly illustrated with eight plates by a single artist, did not even contain a list of illustrations, the remaining Christmas Books had emphasized the pictorial element. In a sense, the second in the series, The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells that Ran an Old Year Out and a New Year In, had set the visual pattern for the series, having thirteen plates (ten of them dropped into the text as a stunning synthesis of pictorial and textual narratives) by four accomplished artists. This team approach Dickens inaugurated almost certainly to ensure that all plates would be ready in time for the December publication date. His illustrators were busy in those days, working for Punch and other illustrated magazines, as well as working on other writers' books. Despite the fact that the illustrations added considerably to the purchase price of Dickens's annual Christmas offering (especially if these were hand-colored) and would thereby decrease his profits (as was very much the case with the Carol five years earlier), Dickens did not merely maintain the program of illustration that accompanied previous Christmas Books; he expanded it. Now, for The Haunted Man Dickens devised a lavish program of seventeen plates, with Tenniel and Leech leading, and Stone and Stanfield supporting. Clearly Dickens placed great confidence in Leech throughout the Christmas Books, for he produced 44% of the total illustrations (28 out of 65 plates). Through his Pickwick illustrator George Cruikshank in July, 1836, while with Bentley's Miscellany, Dickens met John Leech, recommending him to Chapman and Hall for their Library of Fiction. With the exception of Tenniel, the artists were all close friends of Dickens well before he commenced writing The Haunted Man in the summer of 1847. Dickens first became acquainted with Stanfield in Dec., 1837, and with Stone, Secretary of the Shakespeare Society, in March, 1838. Dickens's 30 Oct., 1848, letter to Leech indicates that the leading Christmas Book illustrator had yet to meet Tenniel at that point, and, indeed, that thirty-six- year-old Dickens himself had just met the twenty-eight- year-old Tenniel:

........Mr. Tenniel has been here today and will go to work on the frontispiece. We must arrange for a dinner here [Devonshire Terrace], very shortly, when you and he may meet. He seems to be a very agreeable fellow, and modest. ( Pilgrim Letters 5: 431)

Tenniel (1820-1914) was some three years younger than Leech (1817-64) and considerably younger than Stanfield (1793-1867), but had already exhibited at the Society of British Artists in 1836 and at the Royal Academy (1837-42). Since Dickens's usual engraver, L. C. Martin (whose firm was responsible for seven of the 17 Haunted Man plates) was married to Tenniel's sister, it is surprising that Dickens and Tenniel had not met sooner. The year after illustrating The Haunted Man Tenniel replaced Doyle on the staff of Punch when the latter left because as a Catholic he objected to the magazine's attacks on the papacy. Dickens, not yet aware of Tenniel's capabilities, confined him to ornamental subjects (the frontispiece, the title-page, and the fire-side scene that opens the story proper), and gave over to him what Leech had not the time for, resulting in the extremely wooden renditions of Mrs. Tetterby and her brood, a muffled Redlaw, and "The Boy before the Fire" in "The Gift Diffused" (Ch. 2).

Ruth Glancy in "Dickens at Work on The Haunted Man" expresses the notion that the Christmas Books offered Dickens the rare opportunity "to correct an entire work before it went to press, a luxury not permitted by the serial publication of the novels". In fact, in terms of instructing his artists regarding their illustrations, he had no such luxury at all. Working with Hablot Knight Browne on the Martin Chuzzlewit plates was comparatively simple. In October, 1843, while starting A Christmas Carol, Dickens was writing the November installment, part eleven (Chapters 27, 28, and 29).

The routine during the composition and publication of Chuzzlewit in numbers was similar to that established for the previous monthly serials. The first half of each month was devoted to writing the new installments, the second half to correcting proofs. Subjects for the plates were supplied [to Phiz] as early as possible, usually by the tenth . . . . (Patten 132)

He would furnish Phiz with a clean set of proofs and a list of suggestions for illustration. Phiz would produce sketches which Dickens could then critique; thus, month in and month out, Dickens controlled an orderly program of writing and illustration. Whatever subjects he and Phiz decided upon for the plates was immaterial, since the illustrations occupied whole pages and were included at the end of each part; the reader could locate their realized moments in the accompanying text and, if he or she so desired, have the plates bound in at those points once all nineteen numbers had been acquired.

Now, consider the plates for any of The Christmas Books after A Christmas Carol: Dickens had to direct a team of artists to produce illustrations to be dropped into specific spots in the printed text. The Pilgrim Edition of the Letters of Charles Dickens, Volume V (1847-1849), reveal how tight his creative timeline was. In under two months, Dickens completed the physical act of writing The Haunted Man, beginning on October 5th at Devonshire Terrace, London, and finishing on the night of 30 November, at the Bedford Hotel, Brighton. By November 15th, little more than a month before publication, he had the proofs for the first part, including Tenniel's frontispiece and title-page, but not including Stone's "Milly and the Old Man," to which Dickens did not respond until November 23rd. The day before, Dickens wrote to his point man, John Leech, "With a Stick" (underlined) because he was still not in possession of Leech's illustration of the Tetterby family, which would have to be dropped into the text early in part two. On November 27th, writing Stone from Brighton, Dickens had no proofs for the artist, and had to describe what he had just written ("Sir, there is a subject I have written today for the third part, that I think and hope will just suit you."). By December 1st, Leech was still not in possession of the corrected proofs for the third part, and Dickens, fearing Leech's other work was slowing him down, diplomatically asked him to pass the last illustration, the dinner in the great hall, over to Stanfield (who, though not much of a caricaturist, would handle well the architectural elements of the scene). And yet, by December 13th, Dickens was able to send Mrs. Richard Watson an advance copy, even though Forster probably did not turn over the final proofs corrected until about a week previous. Having no rush proofs for part four, Dickens elected to go twenty-nine pages without a single illustration.

An added complication was that Dickens was supplying Mark Lemon with proofs to facilitate the staging of The Haunted Man, but certainly this break-neck schedule was worse than the measured routine Dickens followed in getting out a monthly serial installment.

I find that very interesting. What I don't understand is why he used so many illustrators for THM. It seems to me all the stuff talked about before this could have been made easier if he was only dealing with one artist. If anyone knows why he used four different artists for one small book, please let me know. Oh, perhaps it would less confusing for us if I listed the four illustrators. They were John Tenniel, John Leech, Clarkson Stanfield, and Frank Stone.

Whereas A Christmas Carol, more modestly illustrated with eight plates by a single artist, did not even contain a list of illustrations, the remaining Christmas Books had emphasized the pictorial element. In a sense, the second in the series, The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells that Ran an Old Year Out and a New Year In, had set the visual pattern for the series, having thirteen plates (ten of them dropped into the text as a stunning synthesis of pictorial and textual narratives) by four accomplished artists. This team approach Dickens inaugurated almost certainly to ensure that all plates would be ready in time for the December publication date. His illustrators were busy in those days, working for Punch and other illustrated magazines, as well as working on other writers' books. Despite the fact that the illustrations added considerably to the purchase price of Dickens's annual Christmas offering (especially if these were hand-colored) and would thereby decrease his profits (as was very much the case with the Carol five years earlier), Dickens did not merely maintain the program of illustration that accompanied previous Christmas Books; he expanded it. Now, for The Haunted Man Dickens devised a lavish program of seventeen plates, with Tenniel and Leech leading, and Stone and Stanfield supporting. Clearly Dickens placed great confidence in Leech throughout the Christmas Books, for he produced 44% of the total illustrations (28 out of 65 plates). Through his Pickwick illustrator George Cruikshank in July, 1836, while with Bentley's Miscellany, Dickens met John Leech, recommending him to Chapman and Hall for their Library of Fiction. With the exception of Tenniel, the artists were all close friends of Dickens well before he commenced writing The Haunted Man in the summer of 1847. Dickens first became acquainted with Stanfield in Dec., 1837, and with Stone, Secretary of the Shakespeare Society, in March, 1838. Dickens's 30 Oct., 1848, letter to Leech indicates that the leading Christmas Book illustrator had yet to meet Tenniel at that point, and, indeed, that thirty-six- year-old Dickens himself had just met the twenty-eight- year-old Tenniel:

........Mr. Tenniel has been here today and will go to work on the frontispiece. We must arrange for a dinner here [Devonshire Terrace], very shortly, when you and he may meet. He seems to be a very agreeable fellow, and modest. ( Pilgrim Letters 5: 431)

Tenniel (1820-1914) was some three years younger than Leech (1817-64) and considerably younger than Stanfield (1793-1867), but had already exhibited at the Society of British Artists in 1836 and at the Royal Academy (1837-42). Since Dickens's usual engraver, L. C. Martin (whose firm was responsible for seven of the 17 Haunted Man plates) was married to Tenniel's sister, it is surprising that Dickens and Tenniel had not met sooner. The year after illustrating The Haunted Man Tenniel replaced Doyle on the staff of Punch when the latter left because as a Catholic he objected to the magazine's attacks on the papacy. Dickens, not yet aware of Tenniel's capabilities, confined him to ornamental subjects (the frontispiece, the title-page, and the fire-side scene that opens the story proper), and gave over to him what Leech had not the time for, resulting in the extremely wooden renditions of Mrs. Tetterby and her brood, a muffled Redlaw, and "The Boy before the Fire" in "The Gift Diffused" (Ch. 2).

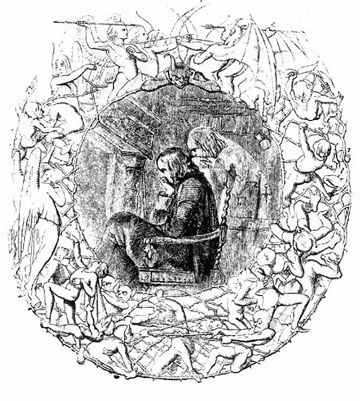

Frontispiece

John Tenniel

1848

Full-page illustration for Dickens's The Haunted Man

Commentary:

The process of illustrating The Haunted Man began in a leisurely enough way, with Dickens interviewing John Tenniel about the initial plates on October 30th, then reporting by letter to his lead artist.

The Frontispiece, a full-page illustration repeated and elaborated on later by Leech's "Redlaw and the Phantom," serves as an overture to the program, but is lacking a caption. Thus, without any mediating textual comment the reader is engaged in the psychomachia of a Christmas holly wreath (preparing him for the closing words of the text, delivered in the final plate on page 188, "Lord, keep my memory green") surrounding the vignette of an apprehensive man, seated before the fire, with a shrouded wraith whispering in his ear.

A horned demon, above, presides over the whole scene. To his left (stage right) angels rise, throwing spears and shooting arrows at demons right as other demons drag human souls down. At the very bottom a soul struggles, enmeshed in latticework. We shall never meet the angels or the demons in the printed text, but soon shall meet the seated professor (Dickens's only intellectual protagonist) and his ghostly double.

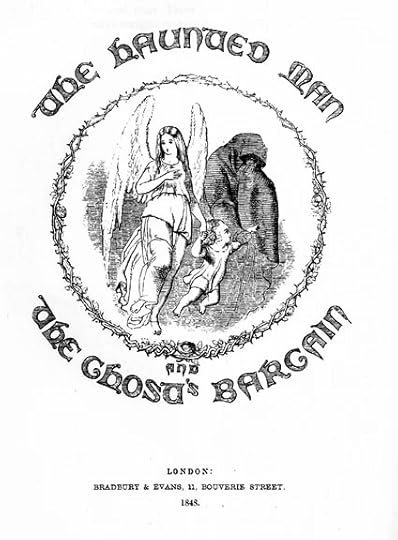

Title Page

John Tenniel

1848

Dickens's The Haunted Man

Commentary:

Tenniel's second plate for Charles Dickens's The Haunted Man (1848), the title-page, is again a full page, but has ornate text surrounding its circular vignette. The female angel with long hair who appears twice on the left-hand register of the wreath in the Frontispiece points the way with her right hand as she takes the right hand of the child with her left. Continuing the right/left symbolism, Tenniel has the dark hooded figure (so reminiscent of the "Ghost of Christmas Yet To Come" in A Christmas Carol) hold the child's left hand. Again, the wreath motif is the unifying structural device, but occasionally these thorns bear a rose and leaves, unlike those in the Frontispiece. Thus, Tenniel's introductory plates make plain the nature of the allegory that the text will present: an acceptance of our lives, past and present, rose and thorn, painful and happy, is necessary for psychological integration and spiritual salvation.

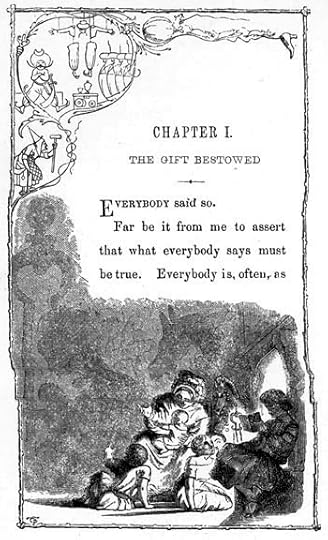

The Gift Bestowed

Chapter 1

John Tenniel

Text Illustrated:

When little readers of story-books, by the firelight, trembled to think of Cassim Baba cut into quarters, hanging in the Robbers’ Cave, or had some small misgivings that the fierce little old woman, with the crutch, who used to start out of the box in the merchant Abudah’s bedroom, might, one of these nights, be found upon the stairs, in the long, cold, dusky journey up to bed.

Commentary:

Tenniel third plate "Chapter I. The Gift Bestowed," illustrates an early moment in the text that occurs immediately after plate four. A mother and her five children, the youngest an infant with whom she is playing, are foregrounded by shadows as they sit by the fire. In darkness, the oldest child is reading a small book, which he holds up to catch the flickering light of the fire, which illuminates the other five figures. Rising like smoke from the shadows are one-dimensional figures whose outlines fill the upper-left register of the page, enclosing the text: an old woman (a witch?) with a crutch, a turbanned Eastern warrior with a scimitar, a puppet, four identical toy soldiers, all surmounted by mistletoe, a round fruit (an orange, perhaps), and four mice running along a vine. In short, we have Tenniel's rendering of the real and imaginary worlds of childhood, connected by the chime or rattle by the reader that is the original of the shadow that, transformed into an ornate shepherd's crook, dominates the left-hand side of the page.

Plate three, we suddenly realize a few pages later, is actually an illustration of the passage after that realized by the fourth plate; plate three complements the passage which describes children reading tales from the Arabian Nights, specifically how Ali Baba's brother, Cassim, inadvertently trapped himself in the robbers' cave (as a result of his failing to remember the magic password) was subsequently cut into quarters, and how an old hag on crutches started out of the box belonging to the merchant Abudah, and exhorted to search for the talisman of Oromanes.

Dickens is clearly recalling his own childhood responses of terror and enchantment when reading these tales: "When little readers of story-books trembled" has been interpreted by Tenniel as one child reading to its younger siblings. Dickens presumably chose to allude to these tales in order to point the moral that Redlaw must learn, that our own self-pity can trap us in a labyrinth of bitterness, and that the only way out, the open sesame, is forgiveness and acceptance. As in many later plates, the illustration encloses a small amount of print.

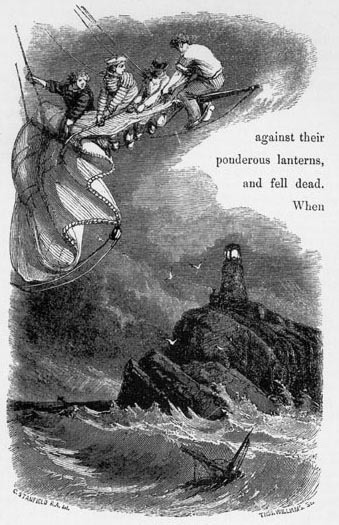

The Lighthouse

Chapter 1

Clarkson Stanfield

Text Illustrated:

When travellers by land were bitter cold, and looked wearily on gloomy landscapes, rustling and shuddering in the blast. When mariners at sea, outlying upon icy yards, were tossed and swung above the howling ocean dreadfully. When lighthouses, on rocks and headlands, showed solitary and watchful; and benighted sea-birds breasted on against their ponderous lanterns, and fell dead.

Commentary:

Stanfield's first appearance in this text is admirably suited to his own personal history (a sailor in the British merchant navy and then the Royal Navy) and abilities as a painter of seascapes. On the bowsprit of a sailing vessel, left, four sailors (two of them quite young) struggle to reef in the jibsheet. Beneath them, in the surf, is an anchor. On a rock darkling rising from the breakers an owl-like lighthouse stands, the small gulls indicating both its size and its distance from the ship (which we must imagine, for only the bowsprit and its five supporting stays are visible). The perilous scene is not allegorical but a visual realization of a passage at the bottom the (left) facing page: "When mariners at sea, outlying upon icy yards, were tossed and swung above the howling ocean dreadfully. When the lighthouses, on rocks and headlands, showed solitary and watchful". Perhaps Stanfield's point is that, as opposed to these sailors who brave the deep for merchants or in service of their nation, Redlaw has enjoyed a comparatively tranquil existence, despite a mysterious trauma in the past that has embittered him.

By virtue of its being located "a league" from shore and "Built upon a dismal reef of sunken rocks" (A Christmas Carol, Stave Three), Dickens's lighthouse would seem to be the famous Eddystone Light, the fourth tower (built between 1756-9) of which he, Forster, Maclise, and Stanfield must have seen eight miles off Start Point in the English Channel when they toured Cornwall (the locale suggested by "A place where Miners live" on the previous page of the Carol). In The Haunted Man, Dickens's reference to "lighthouses, on rocks and headlands" again implies a coastline much like that of the Land's End area, which boasts "the greatest concentration of lighthouses anywhere in the world" ("Lighthouses of Cornwall"). Today, the area has thirteen lighthouses, but in October, 1842, the four friends would have seen only the following six: Eddystone (re-built in 1759 to mark the dangerous reef called, "The Hand Deep"), Wolf Rock (built in 1795 eight miles off Land's End), Lizard (1619), St. Agnes (1680), Longships (1795), and St. Anthony's Head (1835). Before Dickens published The Haunted Man, the new lighthouse at Trevose Head had just been completed 4.5 miles from Padstow on the shore. Ironically, despite the ominous description of the coastline, while travelling in Cornwall Dickens much enjoyed himself in the company of his three friends.

In a letter to Forster (August, 1842), as he was reading about Cornwall and its many lighthouses in preparation for their fall walking tour, Dickens considers the "notion" of beginning his next novel, Martin Chuzzlewit, in the lantern of a lighthouse. It is quite likely that the journey he and his friends had made to the Cornish coast a year previous was still in Dickens's mind in the autumn of 1843, when he wrote A Christmas Carol, and that his notions about rock-bound coasts and lighthouses were thenceforth inextricably connected with reminiscences of that convivial vacation. Dickens's manifest interest in lighthouses was not entirely based on their picturesque locations, for they were part of Victorian Britain's increasing concerns about the safety of merchant shipping, in connection with which one need merely consider such contemporary initiatives as the instituting of instituting of seamanship examinations (1845, 1851) and of the Meteorological Office (1854).

Again, the illustration encloses a few printed words, carrying the reader from the text preceding to the text after the plate.

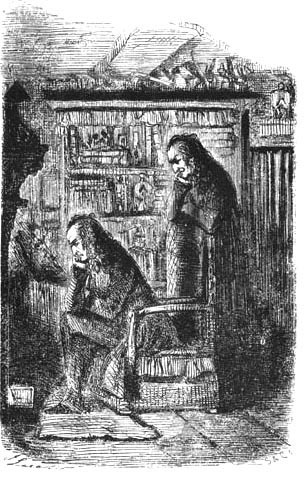

Redlaw and the Phantom

Chapter 1

John Leech

Commentary:

John Leech's opening plate, a full-page vignette on page 34 that treats the Doppelganger scene, compels the reader to return to Tenniel's earlier treatments of the same theme. This time, we have dialogue and explication on the previous page running over to the top of the illustration. How convenient that the sentence "This was the dread companion of the haunted man!" sits immediately above the figures. Leech's chair is less fanciful and his version of the spirit more substantial than their counterparts in the Frontispiece. Leech has made Redlaw's study lighter, permitting us to see far more detail in the bookcase at the back. We can see "his drugs and instruments and books", but not "the shadow of his shaded lamp . . . , motionless among a crowd of spectral shapes" . Thus, not only Tenniel's opening plates but also a textual passage many pages earlier have prepared us for this scene, the second visitation of the Ghost. The moment captured is that before Redlaw notices and addresses the Phantom. While Redlaw gazes into the fire, the Phantom's thoughtful gaze is bent on the Chemist, and not on the fire, too, as in the text: "It took, for some moments, no more apparent heed of him, than he of it". Leech seems to have made this alteration in order to make his rendering of the two parallel Tenniel's.

Gone are the good angels and demons, replaced by commonplace objects, which nevertheless appear ominous in the half-light: is that a skull on the top shelf and a demon's mask above, or are these only ocular delusions? Redlaw's chair in Leech's plate is more prosaic (no carved gargoyle supports the arm of this chair). The spectre does not whisper at Redlaw's ear like Satan at the ear of Eve in Paradise Lost; rather, Leech brings out the physical likeness in their features as Redlaw, seeing past wrongs re-enacted in the flames, is sardonically scrutinized by his double, whose body fades into the back of the chair and the curtain, right. Redlaw's hair is less full in Leech's version; his hairline recedes, giving him a more middle-aged and careworn aspect. His demeanor is not fearful, as in Tenniel, but bemused. In addition to the small library seen also in Tenniel's plate, the bookcase behind the figures contains glass jars, indicative of Redlaw's scientific vocation. Leech has captured the moment on the preceding page when "As he leaned his arm upon the elbow of his chair, ruminating before the fire, it leaned upon the chair-back close above him". One reads page 33 with anticipation, glancing back to examine the textual details more carefully once one turned the page, then moves back to that central moment hinted at in Dickens's title. The curtain to the right appears again, but at the left, in the seventh plate, thereby connecting the two in the pictorial narrative sequence.

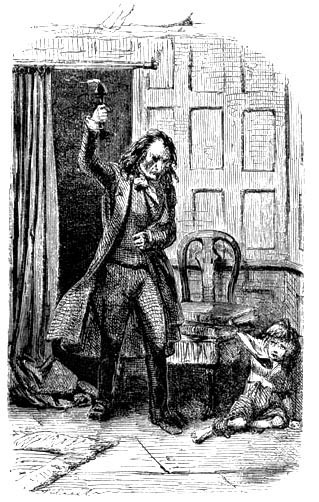

Redlaw and the Boy

Chapter 1

John Leech

Commentary:

Little of Leech's usual sense of comedy and caricature appears in this plate. However, he allows a strongly felt emotion to dominate, as in his "Scrooge and the Spirit of Christmas Yet To Come" in A Christmas Carol. Redlaw has entered, raising the lamp as the street urchin invited in by Milly cowers in the corner: "A bundle of tatters, held together by a hand, in size and form almost an infant's, but in its greedy, desperate little clutch, a bad old man". The precise moment realized is as one turns the page: "Used, already, to be worried and hunted like a beast, the boy crouched down as he was looked at, and looked back again, and interposed his arm to ward off the expected blow". Neither has yet spoken.

The center of the printed page describes the child exactly as we see him in the plate, right. Is he, as John Butt suggests, a more realistic treatment of the boy Ignorance in the Carol plate? Leech's allegorical child in "The Second of the Three Spirits" is a head shorter than his sister, Want, and shivers in the cold, his clothing in tatters, his feet bare, despite the season. The street urchin here has more hair, and his face a mask of savagery rather than an impassive façade. The street child cowers before the blow he anticipates that Redlaw will deliver, rather than from the elements. The industrial smokestacks behind Ignorance and Want are symbols supplied by the radical Punch cartoonist to connect these social problems with the factory system and Scrooge's Malthusian doctrine of "surplus population." in "Redlaw and the Boy," Leech has placed a stack of folios on the chair that separates the pair, books that have no counterparts in the printed text. Perhaps they mutely assert the upward climb that Redlaw has made from childhood through education. "I strove to climb!", since, at a realistic level, the boy can hardly have placed them there in order to steal something from the bare wainscoting. The books, then, serve to connect the unloved child Redlaw once was with the deprived child he sees before him. The Boy, if he is any sort of abstraction, is Hunger. However, the boy is merely "like some small animal of prey". Dickens does not employ metaphor ("wolfish") or allegorical terms ("Where angels might have sat enthroned, devils lurked"), and the artist has charged this boy with a feeling (well conveyed by the pose) quite absent from his Christmas Carol plate. The nameless child has speech (unlike his mute counterpart in the Carol plate), but does not immediately recognize the meaning of "live."

The closed curtain from the sixth plate becomes the just-opened curtain behind Redlaw (left), joining the two scenes. The printed text focuses on the "heavy curtain in the wall, by which he was accustomed to pass into and out of the theatre where he lectured, -- which adjoined his room". Both artist and novelist emphasize the palpable reality of the ghetto child: "A baby savage, a young monster, a child who had never been a child, a creature who might live to take the outward form of man, but who, within, would live and perish a mere beast". Redlaw, with money, position, and education, has the ability, as Scrooge has, to change the prediction.

*

"'Merry and happy, was it?' asked the Chemist in a low voice. 'Merry and happy, old man?'"

Fred Barnard

1878

Commentary:

Barnard's picture of Professor Redlaw (left) and Philip Swidger holding the holly sprig with berries serves as an internal frontispiece for the last of the five Christmas Books, and realizes the following passage about the beneficial effects of memory:

Without any show of hurry or noise, or any show of herself even, she was so calm and quiet, Milly set the dishes she had brought upon the table, — Mr. William, after much clattering and running about, having only gained possession of a butter-boat of gravy, which he stood ready to serve.

"What is that the old man has in his arms?" asked Mr. Redlaw, as he sat down to his solitary meal.

"Holly, sir," replied the quiet voice of Milly.

"That's what I say myself, sir," interposed Mr. William, striking in with the butter-boat. "Berries is so seasonable to the time of year! — Brown gravy!"

"Another Christmas come, another year gone!" murmured the Chemist, with a gloomy sigh. "More figures in the lengthening sum of recollection that we work and work at to our torment, till Death idly jumbles all together, and rubs all out. So, Philip!" breaking off, and raising his voice as he addressed the old man, standing apart, with his glistening burden in his arms, from which the quiet Mrs. William took small branches, which she noiselessly trimmed with her scissors, and decorated the room with, while her aged father-in-law looked on much interested in the ceremony.

"My duty to you, sir," returned the old man. "Should have spoke before, sir, but know your ways, Mr. Redlaw — proud to say — and wait till spoke to! Merry Christmas, sir, and Happy New Year, and many of 'em. Have had a pretty many of 'em myself — ha, ha! — and may take the liberty of wishing 'em. I'm eighty-seven!"

"Have you had so many that were merry and happy?" asked the other.

"Ay, sir, ever so many," returned the old man".

Once again, the British Household Edition of The Christmas Books fails to match the visual interest of the original series' abundant but small-scale illustrations in the last of the scarlet-and-gold-stamped volumes, The Haunted Man (1848). Compare, for example, John Tenniel's elaborate psychomachia in the frontispiece in the original series with Barnard's introductory scene. As angels and demons wage war for the soul of the protagonist, his double, the "Phantom," leans over his shoulder, tempting him to see human existence as a bleak, cheerless Darwinian struggle. Thus, Tenniel establishes from the first the characteristic supernatural dimension of the story, whereas in Barnard's sequence the Phantom appears just once. Although Tenniel reinforces the supernatural or metaphysical element in the "good angel/bad angel" theme of the ornamental title-page, the other illustrators emphasize the domestic bonhomie of the sometimes cartoon-like Swidgers, as opposed to the steady-going domestic realism of Fred Barnard's illustrations. If Barnard's treatment seems to lack the charm of the original volume's depictions of Redlaw and the Swidgers, it is decidedly stronger in its delineation of character than E. A. Abbey's equivalent, "I'm Eighty-Seven!" in the American Household Edition, a wood-engraving which, despite its detailing Redlaw's dinner-table and sideboard as the informing context, fails to reveal much about Redlaw and the two male Swidgers, all of whom seem oblivious to Milly's starting to decorate the room, although the scene is effectively and even sacramentally illuminated by the single gas-lamp on the narrow table (center).

Aside from the Christmas feast in the Great Hall that closes "Part the Second," The Haunted Man lacks the whimsical humor and good feeling of A Christmas Carol, despite the presence of a Cratchit-like family, the Swidgers. On the other hand, as reinforced by the wood engravings dropped into the text, the book does possess a number of "Carol" features.

Having to miss a year in the sequence in order to complete Dombey and Son, in the autumn of 1848 Dickens returned to the Christmas Book "formula" with The Haunted Man, so that the Household Edition illustrations (far fewer in number than the collaborative program of the original edition) necessarily focus on the character and spiritual journey of Dickens's only intellectual protagonist, the university chemistry Professor Redlaw. As Sarah Solberg notes, the frontispiece in the 1848 edition is "distinctly supernatural"; in contrast, the Household Edition illustrations by Barnard and Abbey offer only one "supernatural" scene, namely that of Redlaw entreating the Phantom to undo his dubious "gift" on p. 189 in the Chapman and Hall edition, and are otherwise thoroughly domestic (if not mundane and prosaic). As D. N. Brereton remarks of the domestic note in The Christmas Books:

In The Cricket on the Hearth, and again in The Haunted Man, which deservedly ranks as one of his best stories, Dickens came nearer to repeating the wonderful success of the Carol. In these little domestic idylls he strikes once more a responsive chord in the hearts of all those to whom Home in fancy, if not in reality, is the dwelling-place of sweetness and light.

"'Merry and happy, was it?' asked the Chemist in a low voice. 'Merry and happy, old man?'"

Fred Barnard

1878

Commentary:

Barnard's picture of Professor Redlaw (left) and Philip Swidger holding the holly sprig with berries serves as an internal frontispiece for the last of the five Christmas Books, and realizes the following passage about the beneficial effects of memory:

Without any show of hurry or noise, or any show of herself even, she was so calm and quiet, Milly set the dishes she had brought upon the table, — Mr. William, after much clattering and running about, having only gained possession of a butter-boat of gravy, which he stood ready to serve.

"What is that the old man has in his arms?" asked Mr. Redlaw, as he sat down to his solitary meal.

"Holly, sir," replied the quiet voice of Milly.

"That's what I say myself, sir," interposed Mr. William, striking in with the butter-boat. "Berries is so seasonable to the time of year! — Brown gravy!"

"Another Christmas come, another year gone!" murmured the Chemist, with a gloomy sigh. "More figures in the lengthening sum of recollection that we work and work at to our torment, till Death idly jumbles all together, and rubs all out. So, Philip!" breaking off, and raising his voice as he addressed the old man, standing apart, with his glistening burden in his arms, from which the quiet Mrs. William took small branches, which she noiselessly trimmed with her scissors, and decorated the room with, while her aged father-in-law looked on much interested in the ceremony.

"My duty to you, sir," returned the old man. "Should have spoke before, sir, but know your ways, Mr. Redlaw — proud to say — and wait till spoke to! Merry Christmas, sir, and Happy New Year, and many of 'em. Have had a pretty many of 'em myself — ha, ha! — and may take the liberty of wishing 'em. I'm eighty-seven!"

"Have you had so many that were merry and happy?" asked the other.

"Ay, sir, ever so many," returned the old man".

Once again, the British Household Edition of The Christmas Books fails to match the visual interest of the original series' abundant but small-scale illustrations in the last of the scarlet-and-gold-stamped volumes, The Haunted Man (1848). Compare, for example, John Tenniel's elaborate psychomachia in the frontispiece in the original series with Barnard's introductory scene. As angels and demons wage war for the soul of the protagonist, his double, the "Phantom," leans over his shoulder, tempting him to see human existence as a bleak, cheerless Darwinian struggle. Thus, Tenniel establishes from the first the characteristic supernatural dimension of the story, whereas in Barnard's sequence the Phantom appears just once. Although Tenniel reinforces the supernatural or metaphysical element in the "good angel/bad angel" theme of the ornamental title-page, the other illustrators emphasize the domestic bonhomie of the sometimes cartoon-like Swidgers, as opposed to the steady-going domestic realism of Fred Barnard's illustrations. If Barnard's treatment seems to lack the charm of the original volume's depictions of Redlaw and the Swidgers, it is decidedly stronger in its delineation of character than E. A. Abbey's equivalent, "I'm Eighty-Seven!" in the American Household Edition, a wood-engraving which, despite its detailing Redlaw's dinner-table and sideboard as the informing context, fails to reveal much about Redlaw and the two male Swidgers, all of whom seem oblivious to Milly's starting to decorate the room, although the scene is effectively and even sacramentally illuminated by the single gas-lamp on the narrow table (center).

Aside from the Christmas feast in the Great Hall that closes "Part the Second," The Haunted Man lacks the whimsical humor and good feeling of A Christmas Carol, despite the presence of a Cratchit-like family, the Swidgers. On the other hand, as reinforced by the wood engravings dropped into the text, the book does possess a number of "Carol" features.

Having to miss a year in the sequence in order to complete Dombey and Son, in the autumn of 1848 Dickens returned to the Christmas Book "formula" with The Haunted Man, so that the Household Edition illustrations (far fewer in number than the collaborative program of the original edition) necessarily focus on the character and spiritual journey of Dickens's only intellectual protagonist, the university chemistry Professor Redlaw. As Sarah Solberg notes, the frontispiece in the 1848 edition is "distinctly supernatural"; in contrast, the Household Edition illustrations by Barnard and Abbey offer only one "supernatural" scene, namely that of Redlaw entreating the Phantom to undo his dubious "gift" on p. 189 in the Chapman and Hall edition, and are otherwise thoroughly domestic (if not mundane and prosaic). As D. N. Brereton remarks of the domestic note in The Christmas Books:

In The Cricket on the Hearth, and again in The Haunted Man, which deservedly ranks as one of his best stories, Dickens came nearer to repeating the wonderful success of the Carol. In these little domestic idylls he strikes once more a responsive chord in the hearts of all those to whom Home in fancy, if not in reality, is the dwelling-place of sweetness and light.

As he leaned his arm upon the elbow of his chair, ruminating before the fire

Felix O. C. Darley

1861

Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

As the gloom and shadow thickened behind him, in that place where it had been gathering so darkly, it took, by slow degrees, — or out of it there came, by some unreal, unsubstantial process — not to be traced by any human sense, — an awful likeness of himself.

Ghastly and cold, colorless in its leaden face and hands, but with his features, and his bright eyes, and his grizzled hair, and dressed in the gloomy shadow of his dress, it came into his terrible appearance of existence, motionless, without a sound. As he leaned his arm upon the elbow of his chair, ruminating before the fire, it leaned upon the chair-back, close above him, with its appalling copy of his face looking where his face looked, and bearing the expression his face bore.

This, then, was the Something that had passed and gone already. This was the dread companion of the haunted man!

It took, for some moments, no more apparent heed of him, than he of it. The Christmas Waits were playing somewhere in the distance, and, through his thoughtfulness, he seemed to listen to the music. It seemed to listen too.

Commentary

Whereas earlier illustrators surrounded the morose chemistry professor with scientific bric-a-brac to establish the verisimilitude of his study (and thereby enlist the reader's belief in the Phantom), Darley invests the scene with neither goblins, demons, sprites, or chemical apparatus. He does, however, give the scholarly subject a writing desk and four books, and a low-burning coal-fire in the grate. Behind him and his double, in the shadows, are book-lined shelves. An interesting feature of Darley's composition is his costuming of Prof. Redlaw, who wears the stockings and breeches of the Regency rather than the stove-pipe trousers of the late 1840s. The absence of supernatural paraphernalia, so obvious in the first edition, suggests psychological portraiture, a study in depression rather than possession.

Although the original and subsequent illustrators of the last of the Christmas Books, The Haunted Man and The Ghost's Bargain (1848), have depicted the solitary scientist, chemistry Professor Redlaw, in his book-lined study, but Darley alone focuses on the depressed mood of his subject and cuts out entirely the story's supernatural machinery (except, of course, for the doppelganger).

"I'm eighty-seven!"

E. A. Abbey

Household Edition (1876)

Commentary:

Stone met with Dickens and Leech, still the main Christmas Book illustrator, to discuss the story of The Haunted Man in 1848 [November 19]. Predictably, the painter [i. e., Stone], with his taste for attractive women, was most inspired by Milly Swidger, the redeeming angel in the macabre situation that Redlaw brings on himself by wishing away all memory of the past. The artist made proposed sketches of Milly, ornamenting the dreary college room with holly, assisted by the elderly Philip. Dickens called "CHARMING" the drawing he preferred of Milly standing on the chair rather than the floor, a position that stressed Philip's fragility as did his more noticeably stooped shoulders. [Cohen, 187]

The matronly cap, was Stone's response to Dickens's suggestion that there be some outward and visible sign of her status. Abbey and Barnard have both drawn on this illustration and the 1848 illustrations depicting Professor Redlaw, but have modeled the figures more naturally. Compare, for example, John Tenniel's study of the gloomy scientist Professor Redlaw in an elaborate psychomachia as the frontispiece of the 1848 volume with the same character in the introductory scenes by Fred Barnard and E. A. Abbey in the Household Edition volumes of the 1870s. Tenniel stresses the metaphysical dimensions of the wooden Redlaw's moral and emotional struggle: as angels and demons vigorously wage war for the soul of the intellectual protagonist, his psychological double, the malevolent and leering "Phantom," leans over Redlaw's shoulder, tempting him to see human existence as a bleak, cheerless, Darwinian struggle. Thus, in this illustration uninformed (as it were) by Charles Darwin's ground-breaking 1859 work on evolution, Origin of Species, Tenniel establishes from the first the characteristic supernatural dimension of the story, whereas in Barnard's sequence the Phantom appears just once — and Abbey's three half-page wood-engravings not at all.

Although Tenniel reinforces the supernatural element in the "good angel/bad angel" motif of the ornamental title-page, the other original illustrators emphasize the domestic bonhomie of the sometimes cartoon-like Swidgers, as opposed to the steady-going domestic realism of Abbey's and Barnard's larger wood-engravings in their short programs of illustration. If Abbey's and Barnard's realistic treatments seem to lack the charm of the original volume's depictions of Redlaw and the Swidgers, Barnard's "'Merry and happy, was it?' asked the Chemist in a low voice", a large-scale wood-engraving, is decidedly stronger in its delineation of the characters of Redlaw, the old man, and William than E. A. Abbey's equivalent, which, despite its detailing Redlaw's dinner-table and sideboard as the informing context, fails to reveal much about the relationship between Redlaw and the two male Swidgers, all of whom seem oblivious to Milly's starting to decorate the room, although Abbey ably and even sacramentally illuminates the scene by the single gas-lamp on the narrow table (center). Curiously, although it is highly likely that both Household Edition illustrators had been able to study the fourteen original illustrations (an influence evident in the manner in which both have drawn Redlaw), Milly in Barnard's initial illustration is lacking the matronly cap that fulfilled Dickens's suggestion to Stone and Leech.

Kim wrote: "My thoughts were about Mrs. William and her strange behavior. Decorating with holly, that is. Holly leaves are not soft, they are not a joy to hold, they are jaggy and they hurt, so why would you g..."

Kim wrote: "My thoughts were about Mrs. William and her strange behavior. Decorating with holly, that is. Holly leaves are not soft, they are not a joy to hold, they are jaggy and they hurt, so why would you g..."You're right--I hadn't thought of that, and it is especially odd given that she herself is described as so smooth.

Holly's pretty, though.

"The Phantom "—

Harry Furniss

1910

Library Edition

Text Illustrated:

"I see you in the fire," said the haunted man; "I hear you in music, in the wind, in the dead stillness of the night."

The Phantom moved its head, assenting.

"Why do you come, to haunt me thus?"

"I come as I am called," replied the Ghost.

"No. Unbidden," exclaimed the Chemist.

"Unbidden be it," said the Spectre. "It is enough. I am here."

Hitherto the light of the fire had shone on the two faces — if the dread lineaments behind the chair might be called a face — both addressed towards it, as at first, and neither looking at the other. But, now, the haunted man turned, suddenly, and stared upon the Ghost. The Ghost, as sudden in its motion, passed to before the chair, and stared on him.

The living man, and the animated image of himself dead, might so have looked, the one upon the other.

Commentary:

Furniss's editor, J. A. Hammerton, has selected as a caption for Furniss's study of Professor Redlaw (left) and his doppelganger (right) precisely the same passage that appears opposite John Leech's "Redlaw and the Phantom" in the 1848 edition. However, Furniss has increased the scale of the figures and decreased the distance between them, thereby eliminating most of the background details pertaining to the chemist's study. And Furniss's university lecturer is fuller faced and older than Leech's, presenting a less romantic and anguished profile as he stares into the flames.