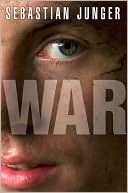

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

moves with a kind of solid purpose that I associate with athletes.

The base is a dusty scrap of steep ground surrounded by timber walls and sandbags, one of the smallest, most fragile capillaries in a vascular system that pumps American influence around the world.

Propped above them is a plywood cutout of a man that Second Platoon uses to draw fire. The cutout is eight feet tall and has a phallus practically big enough to see from across the valley.

The unit that choreographs their actions best usually wins. They might take casualties, but they win. That choreography—you lay down fire while I run forward, then I cover you while you move your team up—is so powerful that it can overcome enormous tactical deficits. There is choreography for storming Omaha Beach, for taking out a pillbox bunker, and for surviving an L-shaped ambush at night on the Gatigal. The choreography always requires that each man make decisions based not on what’s best for him, but on what’s best for the group. If everyone does that, most of the group survives. If no

...more

One of the most puzzling things about fear is that it is only loosely related to the level of danger.

He had such full-on enthusiasm for what he was doing that when I was around him I sometimes caught myself feeling bad that there wasn’t an endeavor of equivalent magnitude in my own life.

O’Byrne is also worried about being alone. He hasn’t been out of earshot of his platoonmates for two years and has no idea how he’ll react to solitude. He’s never had to get a job, find an apartment, or arrange a doctor’s appointment because the Army has always done those things for him. All he’s had to do is fight. And he’s good at it, so leading a patrol up 1705 causes him less anxiety than, say, moving to Boston and finding an apartment and a job. He has little capacity for what civilians refer to as “life skills”; for him, life skills literally keep you alive. Those are far simpler and

...more

Civilians balk at recognizing that one of the most traumatic things about combat is having to give it up. War is so obviously evil and wrong that the idea there could be anything good to it almost feels like a profanity. And yet throughout history, men like Mac and Rice and O’Byrne have come home to find themselves desperately missing what should have been the worst experience of their lives. To a combat vet, the civilian world can seem frivolous and dull, with very little at stake and all the wrong people in power.

When men say they miss combat, it’s not that they actually miss getting shot at—you’d have to be deranged—it’s that they miss being in a world where everything is important and nothing is taken for granted. They miss being in a world where human relations are entirely governed by whether you can trust the other person with your life.

War is a big and sprawling word that brings a lot of human suffering into the conversation, but combat is a different matter. Combat is the smaller game that young men fall in love with, and any solution to the human problem of war will have to take into account the psyches of these young men. For some reason there is a profound and mysterious gratification to the reciprocal agreement to protect another person with your life, and combat is virtually the only situation in which that happens regularly. These hillsides of loose shale and holly trees are where the men feel not most alive—that you

...more

Those collapses were most likely to be caused not by a near-death experience, as one might expect, but by the combat death of a close friend.

If you’re willing to lay down your life for another person, then their death is going to be more upsetting than the prospect of your own, and intense combat might incapacitate an entire unit through grief alone.

Some of those behavioral determinants—like a willingness to take risks—seem to figure disproportionately in the characters of young men. They are killed in accidents and homicides at a rate of 106 per 100,000 per year, roughly five times the rate of young women. Statistically, it’s six times as dangerous to spend a year as a young man in America than as a cop or a fireman, and vastly more dangerous than a one-year deployment at a big military base in Afghanistan. You’d have to go to a remote firebase like the KOP or Camp Blessing to find a level of risk that surpasses that of simply being an

...more

Combat isn’t simply a matter of risk, though; it’s also a matter of mastery. The basic neurological mechanism that induces mammals to do things is called the dopamine reward system. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that mimics the effect of cocaine in the brain, and it gets released when a person wins a game or solves a problem or succeeds at a difficult task. The dopamine reward system exists in both sexes but is stronger in men, and as a result, men are more likely to become obsessively involved in such things as hunting, gambling, computer games, and war. When the men of Second Platoon were

...more

I just want to highlight this whole chapter and it's analysis of the psychologyh of combat so I can come back to this later when I have forgotten the details.

The Army might screw you and your girlfriend might dump you and the enemy might kill you, but the shared commitment to safeguard one another’s lives is unnegotiable and only deepens with time. The willingness to die for another person is a form of love that even religions fail to inspire, and the experience of it changes a person profoundly.

No community can protect itself unless a certain portion of its youth decide they are willing to risk their lives in its defense. That sentiment can be horribly manipulated by leaders and politicians, of course, but the underlying sentiment remains the same.

soldiers in World War I ran headlong into heavy machine-gun fire not because many of them cared about the larger politics of the war but because that’s what the man to the left and right of them was doing. The cause doesn’t have to be righteous and battle doesn’t have to be winnable; but over and over again throughout history, men have chosen to die in battle with their friends rather than to flee on their own and survive.

A soldier needs to have his basic physical needs met and needs to feel valued and loved by others. If those things are provided by the group, a soldier requires virtually no rationale other than the defense of that group to continue fighting.

the willingness to sacrifice one’s life for the group. That’s a very different thing from friendship, which is entirely a function of how you feel about another person. Brotherhood has nothing to do with feelings; it has to do with how you define your relationship to others. It has to do with the rather profound decision to put the welfare of the group above your personal welfare. In such a system, feelings are meaningless. In such a system, who you are entirely depends on your willingness to surrender who you are. Once you’ve experienced the psychological comfort of belonging to such a group,

...more

“Junger is a master at helping readers understand how soldiers feel… The physical and psychological tension for each [of the men] rises through the course of the book. So does the passion in Junger’s narrative.” —NPR.org